Greater's Ice Cream (4 page)

Read Greater's Ice Cream Online

Authors: Robin Davis Heigel

Tags: #Graeter’s Ice Cream: An Irresistible History

The competing story is that soft serve ice cream actually came from Thomas Carvelas, who was forced to sell partially frozen traditional ice cream on the streets in New York after he had a flat tire while delivering the fully frozen version. When customers loved it, he started making the softer version and selling it regularly. In this version of soft serve history, Carvelas actually invented the machine that creates the soft ice cream.

By 1956, soft serve ice cream consumption was increasing by 25 percent a year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And by that year, the three major chainsâDairy Queen, Carvel and Tastee-Freezâhad more than two thousand locations across the country between them.

Another change Graeter's had to deal with was not in terms of competition but in advances in technology. The invention of the home freezer made it possible for customers to store ice cream at home. “In the '30s before the war most of the refrigerators had one little freezer compartment that wasn't separate. You really couldn't store ice cream. Any ice cream that you got you had to eat right away or you bought it out somewhere,” Dick said. “When freezers were separated from the refrigerators, that really led to all the frozen food business. That did change the business significantly.”

Attitudes after the war changed, too, Lou said. “Everybody stayed home and watched TV.”

Staying home and being able to eat ice cream at home led to the production of ice cream novelties such as the Cho Cho Bar, basically chocolate ice cream on a stick, which was sold for a nickel.

ILMER

'

S

W

AYS

As for their own childhood, Dick, Lou and Kathy Graeter, Wilmer's oldest daughter, say they don't remember actually eating that much ice cream. “I don't think we did eat much ice cream when we were kids because I don't think he brought it home,” Dick said of his father. “Ice cream was more of a treat in those days.”

But Dick and Lou both remember their father being able to eat a large quantity of ice cream.

What Kathy remembers most about her father is his work ethic. “He was always a very hard worker. He enjoyed what he was doing all the time,” she said. “He had a real appreciation for what the product is: unique, something special.”

It was also Wilmer, Dick and Lou believe, who came up with the idea of adding chocolate chips to the ice cream. Those chips and the way they are added are one of the hallmarks of the Graeter's Ice Cream enjoyed today.

“Howard Johnson made the first chocolate chip ice cream. And everybody kind of copied from them,” Dick said. But the way Graeter's adds chocolate chips to its ice cream is unique and hasn't changed since they started doing it: melted chocolate mixed with a small amount of vegetable oil is added to the spinning pot of cream, sugar and eggs when the ice cream is almost completely frozen. (The vegetable oil guarantees the chocolate will melt in the mouth at the same temperature as the ice cream, Dick says.) It spins for a few

minutes to harden into a shell and then is scraped off by hand with a paddle into the ice cream, resulting in different size chunks. It is a process that can't be duplicated by the big continuous freezers, Dick says.

“They have a fruit feeder that adds the chips at some point when the ice cream is partially frozen. But they can't do it the same way we do it,” he said. “Ours comes out with actual pieces of chocolate of different sizes. You can't do that with commercial equipment. That's one of the unique things we do that no one else can do.”

Originally, the only flavors Graeter's offered were vanilla and chocolate scooped into a dish or a cone. But Wilmer also had a knack for making molded ice cream. He would pack the ice cream into pretty molds in all sorts of shapes, like flowers and fruits. He would freeze them, unmold them and decorate them using a little hand pump spray atomizer.

“He had quite an artistic flair for them,” Lou said. “We made them to order for Sunday brunches and parties. My dad would pack them on ice and rock salt and hand deliver them.” World War II brought an end to the molded ice cream, and the company never brought it back.

Another treat that has been part of the Graeter family for decades, but never sold, is what they call “lollipops.” To make them, balls of vanilla ice cream are hand-dipped into the same chocolate used to make the chocolate chips, completely enclosing the ice cream. They're served frozen on a stick. Richard says he remembers Dick and Lou making them for family gatherings, but now the responsibility falls to Lou's youngest son, Chip.

Wilmer was responsible for ice cream sundaes at Graeter's, too, creating what he called bittersweet topping sometime before World War II. The ice cream sundae had been invented sometime in the late 1800s, though, like ice cream itself, the actual creation stories vary. One popular story suggests that it

was created and named so ice cream shops could be open on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath. Another version says it was an accident of spilled syrup on ice cream that became so popular that store owners feared they would lose money on it. So they made it a Sunday-only special, giving it its name.

Where Graeter's differed from other ice cream shops of the time was in the chocolate topping it used for the sundaes. All the other ice cream shops simply used chocolate syrup. “My father made the first fudge topping. We call it bittersweet but it's actually fudge. He made that from the Hershey cocoa,” Dick said. “There're two kinds of cocoas you normally have. One is Dutch process, which is processed with an alkali. The other is natural process. The natural process cocoa will get thick when you cook it, whereas the Dutch process, no matter what you do, will not get thick. What he did, what we still do, is use the natural process cocoa to make our bittersweet topping.”

Before the war, Wilmer tried to strike a deal with Hershey's to create a chocolate specifically for Graeter's bittersweet topping. “But the war came along and Hershey didn't want anything to do with us,” Lou remembers. “We were too little to mess with,” Dick said.

Another problem, however, was that chocolate became hard to come by once the war started. It was turned into K rations and sent overseas for soldiers. Chocolate was valued because it was high in calories, and K rations were created to make sure the troops ingested enough calories to sustain them in battle. The chocolate was vitamin-fortified and modified so it wouldn't melt in the heat.

Today, the company uses what it considers a better chocolate for its topping as well as the chips in the ice cream. Both come from a spinoff of Nestle called Mr. Peter's. It's also the chocolate used to make Graeter's candy.

About the same time as sundaes, parfaits became popular at soda fountains and were added to the menu at Graeter's, too.

They were sold in tall glasses as layers of ice cream and sauce topped with whipped cream. The main difference between parfaits and sundaes, according to historians, is the dish in which each is served. Sundaes were served simply in shallow bowls, while parfaits were concocted in tall, thin, tulip-shaped glasses. “Think of it as your fanciest sundae,” said Richard.

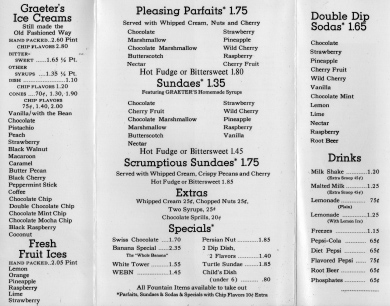

Menus from the '30s show that parfaits sold for thirty cents, while a bowl of ice cream sold for fifteen cents and a sundae sold for twenty cents.

Milkshakes, too, have been part of the Graeter's stores for as long as anyone can remember. Historically, milkshakes and malteds were initially considered health foods. Malted milk was created as an easily digested wheat and malted barley product for infants and invalids. Drugstore soda fountains soon realized they could add the malted powders to ice cream and blend it into a wholesome drink. Milkshakes became particularly popular in the 1920s with the invention of the electric blender.

Richard believes in those days milkshakes were made to be thin, “Something that could be sucked down in ten seconds flat.” Milkshakes today, in Richard's opinion, even those sold at Graeter's, are much too thick. “A milkshake should have just one scoop of ice cream, the rest milk and chocolate syrup,” he said.

In addition to the basic ice cream flavors, Graeter's would, on occasion, offer seasonal flavors, including strawberry and peach, when the fruits were in season. Dick and Lou remember these seasonal flavors, though not necessarily with fondness because of the work entailed for them. “That was our summer job. We always peeled peaches, put them up in wooden barrels and put them in cold storage,” Dick said.

Eventually, the company was able to prep enough peaches to keep in cold storage so it could make the flavor all year. Strawberries, however, were strictly seasonal. “In

those days, they didn't have any prepared strawberries like frozen strawberries. We only made strawberry during the strawberry season,” Dick said. “And that was a nasty job. That was labor intensive. Our dad brought us to work pretty young, pretty early.”

The inside of the menu lists the ice cream flavors, sundaes and other specialties.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Museum

.

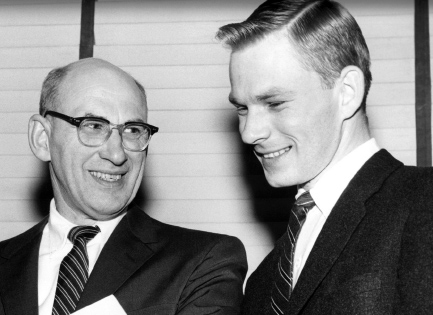

Two men making ice cream in the French pots at the Reading Road plant.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Museum.

Lou also remembers the hard work from a young age. “We were squeezing lemons, peeling peaches. As soon as we got strong enough we were on those French pots,” he said.

IBLING

C

ONFLICTS

Regina, whom everyone called “the boss,” worked with her sons to run Graeter's Ice Cream. But it was no secret that brothers Wilmer and Paul shared an animosity toward one another. “They didn't get along when they were kids,” Lou said. “They never got away from that.”

Regina arranged the business so they both did what they were best at: Wilmer made the ice cream at the plant, while Paul handled the stores and the banking. “Grandma kind of set it up to keep them together,” said Dick.

The problem was the brothers didn't appreciate what the other did. Wilmer was in charge of production of ice cream at the plant with his mother, while Paul managed the stores. Lou remembers his father grumbling that Paul was never at the plant.

“Paul would go around to the stores in the morning. Then he'd come in around noontime and spend about two hours,” he said. “But then he would just leave.”

But Paul did bring positive components to Graeter's, including adding the bakery business that was built up significantly through the '60s and '70s. The bakery is still part of the company today.

Wilmer Graeter (left) with his oldest son, Lou, who also worked in the family business.

Courtesy of Graeter's Ice Cream

.

“We were just going to make desserts. Pies, cakes,” Lou remembers. But they quickly realized that wasn't enough. “They found out they couldn't be in the bakery business unless they started making a little bit of everything. Everything from pies and cakes to rolls and Danish and coffee cakes. I mean the full line of retail baked products,” Dick said.

Today, the company offers that full line of fresh-baked goods, from coffee cakesâincluding the famous double butter cake along with pecan and plain tea ringsâto a range of donuts and Danish rolls, as well as butter-crusted bread, butterbit dinner rolls and, in the summer season, hot dog and hamburger buns. In addition, the company makes decorated cakes, cupcakes, éclairs, cookies, cream horns and turnovers.