Greater's Ice Cream (5 page)

Read Greater's Ice Cream Online

Authors: Robin Davis Heigel

Tags: #Graeter’s Ice Cream: An Irresistible History

One other aspect of the bakery business draws cakes and ice creams together into what was considered a fanciful dessert of the eighteenth century: ice cream cakes, or bombes. Cakes are layered with ice cream and topped with whipped cream and sometimes a chocolate glaze. In addition, Graeter's also makes “wheelies,” or novelties that sandwich ice cream between two cookies. It's a variation of a dessert that gained popularity at the turn of the century in San Francisco called an It's It bar, which was made with oatmeal cookies. At Graeter's, the wheelies are made with chocolate chip cookies.

In Cincinnati, Graeter's also sells its own line of baked goods as well as chocolates.

Courtesy of Ken Heigel

.

After Regina died in 1955 at the age of eighty, her sons tried to work together, but it was an uneasy alliance. Eventually, Wilmer bought Paul out.

“It was either they split up or they probably would have gone out of business,” Dick said.

Wilmer's grandson, Richard, thinks Paul knew it was better for him to go than Wilmer. “He was more sophisticated than

Grandpa,” he said. “He had done well with money, had enough to live on.”

For Wilmer, Richard said, Graeter's Ice Cream was his life.

But the buyout took a certain toll on the family, too. “There was a complete split in our family. When he [Paul] left, it's like he fell off the earth. We never saw him again,” Dick said. It was a lesson Dick and the rest of the family would have to face again, when it was their turn to transition between generations.

When Regina died, the company went through other changes as well. It got out of the novelty business, concentrating instead on ice cream, chocolates and baked goods. Wilmer and his children also decided it was time to reinvest in the company to grow and preserve it for future generations.

If the '50s were a time of home and family, the '60s were a time of great upheaval in America.

The decade introduced the era of the civil rights movement, which led to a time of distinct civil unrest. By 1960, half of the black population had moved from the southern states to urban areas in the North, where many lived in poverty. While many followed the nonviolence preached by Martin Luther King Jr., others found identity in more radical groups that encouraged revolution, such as the Black Panthers.

Cincinnati was not immune to the civil rights struggle. Many blacks in Cincinnati who were displaced by the urban renewal of the '50s, as well as the ones who moved up from the southern states, settled in the Over-the-Rhine area or the West End. The influx gave the neighborhood the highest population density in Cincinnatiâas well as the second-lowest income level of anywhere in the city. New slums were created when landlords subdivided larger houses into smaller apartments. High crime followed. City government tried to

improve the conditions by creating a social services center and concentrating renewal funds on the areas' redevelopment.

But change was slow to come, and the city felt the backlash. Riots that left two people dead broke out in Cincinnati after the shooting death of King in Memphis in 1968.

The '60s were also the time of the women's rights movement. Women fought hard for equal rights, tossing to the wind the notion that true fulfillment came solely from caring for a husband and children. Betty Friedan's

The Feminine Mystique

and the formation of the National Organization for Women (NOW) championed to pass the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution that would have made gender discrimination illegal. The amendment never passed, but greater access to birth control gave women more control over their bodies and, ultimately, their lives.

With women seeking new roles in the world, the concept of marriage changed. Many couples decided to marry later and held off on having children. With the '60s also came a higher rate of divorce.

For Cincinnati, the '60s brought some positive changes, including a new National Football League franchise. In 1967, owner Paul Brown formed the Cincinnati Bengals, named for the Bengal tigers housed at the nationally renowned Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden.

With both a professional baseball and a football team, Cincinnati needed a stadium to support them and their fans. With the help of Ohio governor James A. Rhodes, the city agreed to build a multipurpose stadium on the dilapidated riverfront section of the city. The facility, named Riverfront Stadium, opened in 1970 and was built in the same style as AtlantaâFulton County Stadium, St. Louis's Busch Stadium and Pittsburgh's Three River Stadium. Riverfront, however, was the first stadium in which the playing surface was covered in Astroturf, or artificial grass.

Riverfront, which could hold almost fifty-three thousand people, was also home to the Cincinnati Reds, who became a powerhouse in Major League Baseball in the '70s. The team won back-to-back World Series in 1975 and '76 with players including Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, George Foster and Johnny Bench. During this era, the Reds became known as “the Big Red Machine.”

EW

G

RAETERS IN AN

O

LD

B

USINESS

The third generation of Graeters came into the business in the midst of these changes in the late 1950s and into the '60s, working closely with their father, Wilmer, after he bought out his brother, Paul. The three boys, Lou, Dick and Jon, were all born within two years of one another.

Lou, the oldest, joined Graeter's Ice Cream full time after a couple of years at Ohio State University and four years in the navy. “I got a draft notice, but I didn't want to go in the army,” Lou said. “I wanted to go in the navy.” He waited until he could enlist in the navy, but then he had to serve four years instead of the two required with the draft notice. “It was just as well. I was no good in school anyway,” Lou said. “The day after I got home I came right here.”

Dick graduated from Ohio State and also spent a couple of years in the army. Unlike his siblings, he tried his hand outside the family business. “I actually worked for Gibson Greeting Cards for a couple of years when I got out of the service,” he said. “It was like a management training program there.”

The primary reason he didn't go into the family business, he said, was that everyone else was already in the business. His father and uncle Paul were still partners, and his grandmother was still alive and actively working. Lou went into the business right after the service, not leaving a lot of room for anyone else. “It was already a family business with too much family in it. So somebody had to not be in it,” Dick said. He became part of Graeter's Ice Cream a few years after his grandmother, Regina, died in 1955, about the same time his oldest daughter, Cindy, was born.

Kathy, Dick and Lou Graeter are three of the five grandchildren of Louis Charles and Regina Graeter.

Courtesy of the Graeter family

.

Like his brothers, Jon came into the business after college, handling the company's finances.

Kathy, the only girl in the family business, worked in the stores or at the plant in the summers between school. She was an avid and accomplished tennis player, winning eight singles titles at the Metropolitan tennis tournament in Cincinnati and an international mixed doubles tournament in Monaco. But she says she never gave any thought to joining the professional circuit. In fact, she said she never had any thoughts of doing anything but working in the family business. After graduating

from Northwestern University, she joined the Graeter's team and was put in charge of the retail stores in 1962. She did, however, continue to play competitive tennis, remaining a number-one seed at area tournaments through two more decades.

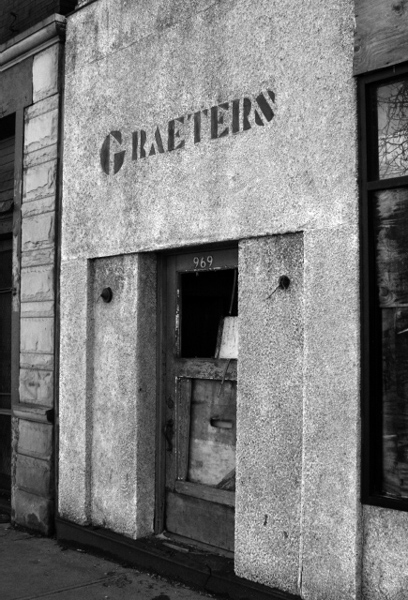

The original Graeter's store on McMillan still shows the hand-lettered sign, even though the building itself is now dilapidated.

Courtesy of Ken Heigel

.

For her professional life, Kathy said that working with her dad and her brothers was a good experience. “We always respected each other. It's just kind of in your blood.” Nonetheless, Kathy was not made an owner until decades later, when Jon retired and she was able to buy out his shares.

One other sister, Carol, never became part of the business, though she, too, worked summers at the retail stores.

Dividing up who managed which aspects of the business happened naturally, the siblings say. “I wound up kind of in charge of the bakery. Lou did the candy. Father did the ice cream,” Dick said. “They made me do a little bit of everything. I kind of gravitated toward the bakery a little bit because there really was nobody doing that. And it was a pretty crude operation.”

The family spent much of the '60s and '70s reinvesting in the company, something that hadn't been done in the decade before. In 1972, they finally closed the original store on McMillan Street because the neighborhood had become so poor. They sold the property in 1974.

ODLES OF

C

OMPETITION

The decades managed by the third generation of Graeters came filled with challenges but with some unexpected help, too. The ice cream business was steady but slow in the '60s, but then it started to pick up.

“I think what changed, what helped our business as much as anything, was people like Baskin-Robbins when they moved

in the Midwest,” Dick said. “I think that did as much for our ice cream as anything. Because it got people interested and thinking about ice cream cones, sundaes and that type of thing more than they had before. Before that people started eating ice cream at home.”

During the '60s, most people would only go out occasionally for ice cream cones. However, they would stop by Graeter's to buy pints of ice cream to take home on a more regular basis. “That business grew significantly through the '60s and '70s,” Dick said.

But when Baskin-Robbins came along, the ice cream landscape changed. Baskin-Robbins was started in Pasadena, California, by brothers-in-law Burt Baskin and Irv Robbins in the 1940s. The stores became franchise only because Baskin and Robbins felt that on-site managers with a financial stake in the company would maintain the quality better. The stores focused on “fun” flavors such as bubble gum and pralines 'n' cream. By the mid-'60s, the company had more than four hundred stores nationally. In Cincinnati, Baskin-Robbins tried to open stores in the same neighborhoods as Graeter's but met with little success.

“It cost you the same for an ice cream cone at Baskin-Robbins as it did at Graeter's,” Dick said. “But it was an obvious difference in the quality between ours and theirs. They didn't [succeed] because people could compare one with the other, and ours wasn't really significantly more expensive, but it was significantly better. All ice cream is good. Ours, I like to say, is unique. People like the uniqueness in a product.”

A story by the

Cincinnati Enquirer

in 1979 led the way for the rivalries between the upcoming national brands versus local favorites. In an unofficial taste test with children as judges, Graeter's outscored Baskin-Robbins in the strawberry flavor (the other longtime Cincinnati ice cream maker, Aglamesis

Brothers, took first place). Outsiders Baskin-Robbins came in first in the chocolate tasting, outscoring Graeter's and the Aglamesis Brothers. Häagen-Dazs, the other national brand in the taste test, never scored better than Graeter's.