Greater's Ice Cream (6 page)

Read Greater's Ice Cream Online

Authors: Robin Davis Heigel

Tags: #Graeter’s Ice Cream: An Irresistible History

Coloring pages such as these with an alien/robot theme were often given out to kids who visited Graeter's.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Museum.

Inside, the Hyde Park store still feels like it did ninety years ago when it opened.

Courtesy of Ken Heigel

.

The tasting was not a sign of strong competition for Graeter's, however. Today, there are only three Baskin-Robbins locations in Cincinnati, while there are fourteen Graeter's Ice Cream stores.

Along with fun, Baskin-Robbins competition proved to be good for Graeter's on another level. The advent of “super-premium” ice cream brought national players with deep pockets, including Häagen-Dazs and Ben & Jerry's, into the market.

Before the late '70s and early '80s, the ice cream market could be basically divided into two categories: premium ice cream and value ice cream. The main difference was in the quality of ingredients and the amount of butterfat and overrun, or air pumped into the ice cream during the processing. The more air, the less dense the finished product. Super-premium ice cream introduced the country to a whole new version of the sweet treatâor so some of the makers wanted the public to believe. In actuality, Graeter's had been making a super-premium ice cream all along.

Häagen-Dazs came out of a company called Senator's Ice Cream in New York that had spent years in the first part of the 1900s making cheap ice cream with high overrun and low butterfat. Its high-end entry started in the late '50s by switching the old formula on its head, with a low overrun and high butterfat, a similar product to what Graeter's had always made.

Super-premium ice cream was also significantly more expensive than other value and premium brands on the market, which made its popularity seem counterintuitive. The '80s brought a humbling recession, an unemployment rate of a historically high 7.5 percent and inflation at more than 13 percent. But at the same time, consumers wanted higher-quality products and were willing to pay for them. The mentality seemed to be that maybe consumers couldn't buy a new house or car, but if they were going to buy ice cream, it was going to be the good stuff, not sweet, artificially flavored frozen air.

On a menu from Graeter's probably from the '60s or '70s, the business tradition is explained.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Museum

.

Despite the health concerns that cropped up later in the decade, ice creamâespecially super-premium ice creamâbecame an affordable indulgence. In

Ben & Jerry's: The Inside Scoop

, author Fred “Chico” Lager wrote, “Weight Watchers had studies that showed that ice cream was the number one food people gave up their diets for. It was America's favorite dessert, and people seemed more inclined to make an exception for ice cream than anything else.”

With its faux Danish name (Häagen-Dazs does not translate into anything in Danish or any other language; owner Reuben Mattus made it up) and high-quality product, Häagen-Dazs created a newfound appreciation for ice cream. By the '80s, all the major manufacturers had come out with super-premium lines of ice cream with foreign-sounding names, such as Frusen Gladje, Le Glace de Paris and Alphen Zauber.

Ben & Jerry's was a similar high-quality product with humble roots, this time in Vermont in the late '70s. What

made Ben & Jerry's different was its social conscience. The company used local products to support farmers and gave money to help fund charities, such as a drug counseling center and homeless shelter in Harlem. It also set up a nonprofit arm called Ben & Jerry's Foundation, to which a portion of the company's profits were granted. The foundation then donated the money in the form of grants to other nonprofit organizations.

Unlike elegant, super smooth Häagen-Dazs, Ben & Jerry's turned to super-chunky fun flavors such as New York Super Fudge Chunk, Dastardly Mashâa combination of pecans, walnuts, chocolate chips and raisins in a chocolate ice cream baseâand Cherry Garcia with cherries and chocolate.

And while Häagen-Dazs was slick, Ben & Jerry's was homespun. In those days, co-founder Ben Cohen was known to say, “We're the only super-premium ice cream whose name you can pronounce.”

Both companies rolled out a limited number of scoop shops across the country but also made their ice cream available by the pint at some grocery stores. (Both companies have since been purchased by large corporations: Häagen-Dazs by Pillsbury, which was eventually acquired by Nestle, and Ben & Jerry's by Unilever.)

To compete with these new super-premium ice creams, Graeter's turned to grocery stores. The company had sold its products to an exclusive market called Washington Market in the TriBeCa neighborhood of New York in the early '80s but was surprised to discover that the store was in turn selling the pints for a whopping $8.85 (in Cincinnati, at the time, a pint went for $2.50).

So in 1987, Graeter's decided to stay closer to home and struck a deal with Kroger, the largest grocery chain in the Midwest, to start selling Graeter's pints. By 1990, eleven Kroger stores also had soda fountains so customers could get

a scoop of ice cream while they shopped and could then pick up a pint to take home.

But one newcomer of the '80s proved decidedly difficult for ice cream producers, including Graeter's: frozen yogurt. During the '80sâand ever sinceâconsumers became concerned with sugar and fat, two things ice cream couldn't be made well without. About the same time, a new product, frozen yogurt, came onto the market.

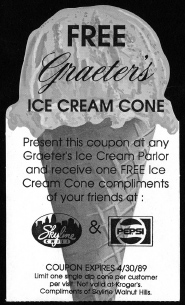

The front of a coupon from 1989 offers a free scoop of ice cream from Graeter's stores.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Museum.

Frozen yogurt is made much like ice cream but with milk and water instead of cream and eggs and with the addition of yogurt culture. When frozen yogurt was first introduced in the '70s, it was a dismal failure because consumers thought it tasted too much like regular yogurt. Manufacturers reformulated the product into something sweeter and more like soft serve ice cream, but still with a “healthy halo.” A half cup of TCBY frozen yogurt, one of the most popular shops that popped up during the era, contained roughly half the calories, less sugar and just a fraction of the fat of a half-cup portion of Graeter's Ice Cream. Later, some frozen yogurt took on more of a traditional hard-frozen ice cream appearance, and makers including Häagen-Dazs got in on the action.

Dick said sales in the '80s leveled off specifically because of the introduction of frozen yogurt. But he didn't worry; he considered the treat to be a flash in the pan.

“Frozen yogurt is the fad food of 1988,” said Dick in an article in the

Cincinnati Enquirer

in 1988. “It's a fad that will grow and will peak, and then it will start dropping off. We'll wait until the fad passes.”

Dick was right about it being a fad. By the '90s, soft serve frozen yogurt had all but disappeared, though new versions such as Pinkberry and Red Mango have started making another run on the ice cream market in the latter part of the first decade of the 2000s. And refrigerator cases at supermarkets still contain a brand or two of hard frozen yogurt, including Häagen-Dazs and UDF.

EW

” F

RENCH

P

OTâAND

F

RANCHISEES

If the steady competition wasn't challenging enough, during the same time it became clear that the company would have to begin replacing some of its aging French pots. Graeter's was still using the same cypress wood vats, old tin bowls and maplewood paddles for scraping the ice cream from the sides of the pots. “We basically made ice cream on one-hundredyear-old antique ice cream machines,” Richard said.

The family needed something new and more reliable that wouldn't compromise the high-end, handmade quality of their ice cream. It proved difficult to find a suitable replacement.

For a time, they turned to Alvey Washing Equipment Company in Cincinnati to make stainless steel vats to replace the cypress bowls. They switched from the maplewood paddles to a plastic composite. But the new version of the actual machine was harder to replace.

When Dick attended a bakery trade show in 1978, he saw an ice cream maker made by an Italian company called Carpigiani that was similar to the French pot. Instead of a

hand-operated paddle, it had a corkscrew scraper that turned automatically. The company bought one machine to see how it would work.

The results were good enough that Graeter's could achieve one of its long-term goals: making the ice cream in-store instead of just at the plant. The first place Graeter's tried this was at the Colerain Avenue store.

But ultimately, the Carpigiani machine didn't work for Graeter's. “We finally decided they weren't heavy-duty enough for what we were doing with it,” Dick said. The machine was designed to make gelato, a slightly softer version of ice cream than what Graeter's produced.

But it did give them an idea of what they needed in a new French pot, and the company set to work at designing its own machine. “We probably reinvented that machine a couple of times,” Dick said. “I know we had to spend a million dollars over time, maybe more.”

Graeter's Ice Cream now manufactures the machines it uses for production today, still using the basic principle of the French pot. It doesn't have a patent on the actual machine, though it considers the company that makes it to be proprietary information. Still, Dick said he doesn't worry about anyone stealing the concept. “Nobody really wants to make product this way.”

In the end, it's the production that sets ice cream apart, according to Dick. All ice cream recipes, he says, are basically the same. “There's no real secret recipe to ice cream. There's cream, sugar and eggs,” Dick said. “I don't care whether it's Häagen-Dazs or Ben & Jerry's or Graeter's. It's still cream, sugar and eggs.”

XPANDING BY

F

RANCHISING

With a number of retail stores running successfully, the Graeters decided to try expanding their business by franchising in the '80s.