Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (29 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

“Can he hear if we shout?”

I didn’t bother answering. This question had been asked of me many times when I was in public with my father. When I answered, “No, he is deaf,” hearing people would often then shout at him over and over. When he didn’t respond, they would walk off in disgust.

“Stupid hearing people,” my father always said to me when this happened. “Pay no attention to them.”

“Where does your father work? Does he have insurance? Do you have a telephone? Do you have a mother? Is she deaf? What’s her name? How can we reach her?”

On and on it went. I answered as best I could.

“How come you can hear?”

I couldn’t understand what that had to do with anything.

“How old are you?”

That one I answered with no problem.

The flap of skin was sewn back to his arm with enough stitches to remind me of my model-train tracks, and he received a transfusion of two pints of blood. Then I spoke to my father’s doctor. Or rather he spoke to me.

“Tell your father he’s lost a great deal of blood,” the doctor said.

“Brilliant man,” my father signed, his damaged arm thickly encased in gauze and tape from wrist to elbow.

“My father says thank you for advising him of that fact.”

“Tell your father he has to keep his arm dry for the next week, change the dressing twice a day, and apply ointment each time he changes the bandages. I will give you a prescription for the ointment. Tell the druggist you want the ointment in a tube, not in a jar. Tell your father he must drink at least eight glasses of water a day, and he should eat lots of meat, like calves’ liver, as he is anemic from the loss of blood.”

While the doctor was telling me all this, my father was watching the doctor’s mouth with little comprehension but growing anxiety.

“What did the doctor say?” he kept interrupting.

“Later,” I answered. “I’ll tell you later.”

“No! Tell me now! I’m not a child!” My father flung angry signs at me, accompanied by his harsh deaf voice.

The people in the hospital corridor stared with rude fascination at my father and his excited hand-signing. Others looked on in disgust and cringed at his screeching deaf voice, which reverberated down the hallway, stopping people in their tracks.

With my brother at my side, I wanted to shout at them,

What are you looking at? We’re not freaks.

My father saw my eyes drift away from his and understood what he read in my face, my shame and anger, guilt, and embarrassment.

“Pay no attention to the hearing people,” he fairly shouted at me in sign. “They are stupid. They don’t know better. They don’t know our deaf ways.”

As I began to explain to my father what the doctor had said, the doctor interrupted me, saying, “I’m quite busy. I can’t spend more time with your father. Tell him—”

My father pulled my arm.

“What is the doctor saying?”

His signs squeaked like chalk across the blackboard of my mind.

I begged the doctor to be patient with my father. I asked my father to be patient with me. I assured my brother that our father would be all right. And my head began to throb with a headache.

Eventually I transmitted all the necessary instructions from the doctor to my father, my father’s many questions to the doctor, and the doctor’s abrupt answers to my father in highly edited form.

At last my father was satisfied and we went home.

I sat between my father and my brother in the subway car, the three of us leaning into each other, away from the other passengers. I answered as best I could the additional questions that occurred to my father. My brother had no questions to ask. He was simply grateful to be going home.

Suddenly my father took me in his arms and kissed my face. “I’m sorry I need you to be my voice in the hearing world. Especially when there is a big emergency.” He looked deeply into my eyes and told me he loved me and was proud of me this day. His sign for

proud

was expansive. His thumb rose against his chest, tracing a passage from waist to neck, while his chest expanded with exaggerated pride.

After what seemed an eternity, we were home. When my father rang the bell, triggering the bulb inside the apartment that announced our arrival in flashing lights, my mother threw open the door. She was frantic, a look of naked fear spread across her face. She had no idea what had happened to her family. She had arrived home to an empty apartment, seen the blood, and realized there had been a terrible accident. But who was hurt? Who had shed so much blood? And where were we? She did not know. She had had no one to ask. She had no phone, nor any way of using it if she had one, and we had left in too much of a panic for me to have thought about writing her a note.

At the sight of my father my mother’s fear dissolved into such profound relief that it nearly broke my heart. An explosion of joy burst across her face, and she made sounds I had never heard her make before: sounds from her heart. Paying no attention to his bandages, she flung herself into his arms. With his damaged arm, my father held her close, burying his face in her hair. My brother and I were completely ignored.

As young as I was, I understood what her reaction meant: she had not, after all, lost her only partner in silence in this alien hearing world. And even at that early age the thought came to me:

What would it be like if one of them died and the other had to go on living? How could they endure the loss?

I knew deep down that in some way I had aged this day, and that I now understood the isolated world of my deaf father and mother as I never had before.

21

My Brother’s Keeper

S

hortly after his diagnosis of epilepsy, my brother was put on a daily dose of phenobarbital, which impeded his ability to function both physically and mentally. Phenobarbital was such a powerful drug that the Nazis had used high doses of it to kill children born with diseases and deformities that kept them from meeting the so-called standards of the Aryan race. Of course, we didn’t know that during the years it was being administered to my brother. But we could see, only too clearly, that his daily dose often left him confused, and so lethargic that he sometimes appeared to be sleepwalking.

Nonetheless, he was never held back in school. This, of course, created many problems. Since he had no way under the circumstances to keep up with his schoolwork, on many occasions his teachers sent him home early with a handwritten note requesting that my father come in for a conference.

These meetings meant that my father had to get a half-day off from work, and that I had to get permission to skip a half-day of school. The former was a hardship, the latter an embarrassment. Prior to each of these school meetings, my father insisted that we take my brother in to meet his doctor, so as to get a professional opinion of his ability to do the work.

During these meetings my role as interpreter for my father was put to the maximum test. At the doctor’s office I had to interpret for my father the doctor’s assessment of what could be expected of my brother, and the medical reasons for those expectations. Then I had to interpret for the doctor the questions my father wanted to ask in response. The resulting delays in their communication soon became frustrating for both of them.

To compound the difficulties of this linguistic Gordian knot, the doctor’s nurse kept popping in to breathlessly announce that the waiting room was filled to capacity and that the doctor’s patients were threatening to find another doctor, one who was not so busy. Of course, I had to interpret this for my father as well.

“So tell her to tell those idiots to get another doctor,” my father instructed me. Whether he was serious or not, I never knew. I mouthed some unintelligible but bland nonsense in the general direction of the nurse as she turned and left the office, hoping my father couldn’t read my lips.

And all the while my brother would be looking at me beseechingly, waiting for me to explain what was going on around him and, I thought, to speak up for him. In these situations, with both the doctor and my father clamoring for my attention and my translations, I was hard-pressed to take the time to give my brother the reassurance that he so badly needed.

As I grew older, my resentment of my brother’s dependence on me faded. I felt sorry for him—for the state of near helplessness to which the epilepsy and the treatment for it had reduced him, oscillating between seizure and recovery, and for the way he tried so hard to be just like the other kids on our street. But the epilepsy did gradually loosen its grip on him, until, at about the time he turned ten, his epileptic seizures stopped, just as suddenly and inexplicably as they had begun. He was at last relieved of his daily torture: the bruises from his falls, the swollen, bitten tongue that filled his mouth, the chipped teeth, and the nausea and headaches that lasted for hours.

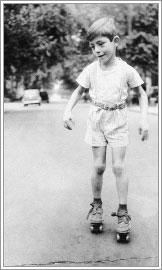

Once he was able to go off most of his medications, he gained some confidence and embarked on what would become his childhood passion: roller-skating. Tentatively, then with growing trust in his newfound abilities, he went on skating excursions around our neighborhood. At first he could barely navigate on his wobbly ankles the length of our block. Eventually, with dogged determination, he could skate around our block—up Ninth Street to Avenue P, around the corner, down Tenth Street to Stillwell Avenue, and back to our building on Ninth Street. In time he would, with ever-increasing skill, be able to skate from our block to Coney Island, three miles away, and then back again. At the meetings with our family doctor, and then with my brother’s teachers, I would offer this newfound skill, and the discipline that made it possible, as an indication that he could also keep up with his schoolwork.

Irwin on his roller skates

The doctor visits always proceeded in the same way. After talking to all of us and doing seemingly endless tests on my brother to ascertain his cognitive abilities, the doctor invariably instructed me: “Tell your father that with extra attention your brother can at least keep up with his grade level.”

After each such visit to the doctor we would go to my brother’s school, where I would resume the back-and-forthing of my role as translator. Round after round of meetings would ensue, and at each meeting a teacher would ask the foundational questions: “Who will be responsible for helping the boy keep up with his classmates?” Silence. Much looking at one another. Much sage nodding of heads. “Who will be providing the extra hours of work explaining the boy’s homework to him?” Continued silence. Eye-avoiding looks. Heads bobbing. “And who will be monitoring his progress on a daily basis?”

I interpreted each of the teacher’s questions for my father.

“Well?” the teacher would demand, looking at my father for the first time during this protracted conversation. Normally, in these types of interactions, the hearing person never looked at my father but rather at me. As for my father, to them he might as well have been a tree stump.

“Well…” my father hesitantly signed, staring helplessly back at the teacher. My brother, knowing that he was the focus of this back-and-forth exercise, looked at them both, while they in turn looked back at him.

Then, as one, they all looked at me.

H

ide-and-seek was a wildly popular Brooklyn street game that we kids played with youthful abandon and enduring passion. Its rules were simple. To begin the game, one unlucky person was designated It. This kid, so identified, would remain It until he (girls had no interest in this game) succeeded in tagging another unlucky kid, while shouting, “You’re It.” And so the game continued, with successive kids becoming It, until we were too tired or bored to play any longer.