Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (32 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

One day in early August my father accompanied me, newly bought suitcase in hand, to Grand Central Station, where I would catch the train to Boston. I was dressed in a heavy wool tweed suit. It was about ninety degrees in the station. I did not sign one word of complaint. As the conductor shouted “All aboard!” my father looked me over one last time and signed, “You look like a college man for sure.” Then he added, “I’ll see you soon.” Little did I know how true that would be. For the next four years my father came to almost every home game we played, always carrying a heavy CARE package that my mother had lovingly prepared all that week.

Stepping onto the train that day, I took the final step, the step from my parents’ deaf world, so familiar yet so foreign, to my own world, the world of the hearing.

Thereafter, when I was with my parents, I would be only a visitor to their world of eternal silence. It had been, for me, a world of great beauty filled with limitless love and, God help me, frequent shame. It had also been a difficult world in which a child had had to play the role of an adult.

The sign for

responsibility

is a dramatic one and leaves little room for doubt as to its meaning. It was one of the first signs my father taught me. He would place both hands, fingertips relentlessly pressing downward, on his right shoulder. His shoulder would slump, as if bearing a great burden, and his face would assume a look of patient endurance. This was what was always expected of me: to be responsible—for my father and his needs, and then when my brother became sick, for my brother, too. There were times when I found this burden crushing, and those were the days when I would rush from my apartment to the roof of our building and hide for hours on end.

Now as I sat on the cushioned seat of the railroad car directly over the iron wheels that relentlessly carried me away, with each revolution, from the only home I had ever known, I felt a lifting of this ever-present burden of responsibility. From now on I would not be responsible for my father or my brother. They would have to manage for themselves.

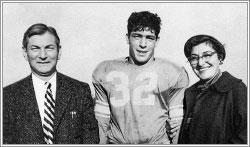

My mother and father after a football game at Brandeis University, 1951. We won.

My sense of relief, however, was diluted by an inexplicable sense of loss. It had never occurred to me that I would feel that way.

26

The Duke of Coney Island

M

y uncle David was my mother’s favorite of her three brothers. “He is a magician, a sorcerer,” she always said of this brother, who was one year younger than she. David was a sorcerer to my mother because, with a wink of his devilish brown eyes, he could transform her sadness into joy. He treated her deafness with remarkable nonchalance. Where every other member of her family made my mother feel different, David acted as if her deafness were nothing more important, or significant, than the color of her eyes or the texture of her hair.

Everyone in my mother’s family, as well as all of his many friends, called David “the Duke of Coney Island.” This was in acknowledgment of his suave manner, his elegant clothes, and the way he managed to get by in such high style with no steady job.

David and my mother were both splendid swimmers. With the sun rising over the beach at Coney Island, holding hands and laughing, they would launch themselves into the Atlantic Ocean and swim until they were out of sight. My mother’s powerful, tanned arms would cleave the water, and she and her white bathing cap would grow ever smaller until, at the edge of the horizon, she and David disappeared.

I always waited patiently on the shore, my father and brother at my side. My father, who was great with his hands, helped us build the most intricate and fantastic sand castles, as we sat and waited for my mother to emerge from the sea.

My father never joined my mother in the water, as he could barely swim three consecutive strokes without stopping to gasp for air. But before diving in himself, David always made a show of grabbing my father’s arm and trying to drag him into the water, while my brother took the other arm and, digging his toes into the sand, pulled in the other direction. This was just a game they played—there was no way my father would go into the ocean with David. “I grew up in the Bronx,” my father would explain, if anyone wondered why he remained on shore. “No ocean.” For him, that explained almost everything, the Bronx being a provincial backwater to cosmopolitan Brooklyn, with its magnificent stone bridge at one end and the great Atlantic Ocean washing up on the beach at the other.

Eventually, with the sun now high in the sky, I would spot a white dot bobbing between the swells. As I watched, the dot became my mother, her strong brown arms cutting through the water as she swam to shore, followed closely by David.

Sometimes she caught me unawares. Riding an incoming wave like a porpoise, she would slither from the surf, a sea creature, and take my sun-warmed body into her icy-wet embrace.

“Where did you go?” I always asked.

“Ireland,” she finger-spelled, with a straight face. “Very green.”

In addition to being a great swimmer and a sorcerer, David was a wizard. He could do magic tricks—wondrous, surpassingly amazing sleight-of-hand stunts that left me gasping.

Beginning when I turned six, he began the ritual of pulling objects from my ear on every birthday. That first year it was a penny. When I turned seven, it was a nickel. At eight, he produced a dime from the depths of my ear. And at nine, a quarter. The following year it was a half-dollar.

The year I turned eleven, my uncle David, after much hocus-pocus, rolled up the sleeve of his right arm and, with great exaggeration, displayed his empty hand under my nose. Wiggling the five digits in the air, he proceeded with infinite slowness to curl his middle finger, then the finger to its left, and finally his pinky into a ball. With the remaining forefinger and thumb, he formed a pincered claw.

Slowly he moved the claw to my ear, then into my ear, and with much grunting and twisting, he extracted a gleaming uncirculated silver dollar. It was magnificent.

Placing the silver dollar on its edge, with a deft twist of his fingers he set it spinning on a nearby surface. “This coin reminds me of you,” he said before the coin came to a stop. I nodded solemnly, not having a clue as to his meaning.

Many years later, when we were both living in Los Angeles, I was riding in a car with my uncle when he asked me if I remembered my eleventh birthday and the silver dollar he had pulled from my ear.

He then explained what he had meant to say to me that day when he had set the coin spinning. As a child, David said, I always seemed to him to be two sides of the same coin, both one thing and its opposite. I was cleaved into two parts, half hearing, half deaf, forever joined together. And he had observed, very astutely, that I vacillated and vibrated between the child that I was in years and the adult I was forced to be in thought and action. When he looked at me, he saw that I stood at the crossroads of sound and silence, of childhood and adulthood, and that I would have to struggle to find my own way.

With his explanation I realized, perhaps as never before, how hard I had fought, all of my young life, to break free from my father’s eternal need of me. It was a struggle that I waged to assert my independence, my very right to be a child. But it was a struggle I fought with one small hand tied behind my back, since I could not let my father think for even one moment that I was abandoning him and the overpowering burden of his deafness.

On that long ride I took with my uncle, across Mulholland, over the Sepulveda Pass, and down into the Valley, heading toward his apartment, I thought about the other side of my childhood’s equation: my mother’s need of me. As her firstborn hearing son, I met a need in her that was of an exclusively practical, utilitarian nature. Unlike my father, she used me only for the nuts and bolts of her everyday forced interactions with the hearing world:

What is the price of this? The availability of that?

Perhaps the differences between my mother and father had to do with the fact that my mother had been deafened as an infant. She had no memory of sound, which for her was intangible, an abstraction, merely an idea. But my father, unlike my mother, had been deafened later in life. Until the age of three he could hear. Somewhere, buried in the folds of his brain, was the memory of sound. That memory, elusive, fragmentary, would not release him. It hovered somewhere always on the horizon of his consciousness. Through me he would try to find it, to tease it into being. And he looked to me to provide the clues.

My father needed me to help him remember sound. To understand sound itself. The very essence of sound. Sound in all its guises. Sound in all its permutations. The shape and physicality of sound. Even the color of sound. Or as a synesthete might, the sound of color.

He struggled all of my young life to fathom spoken speech. How could it be that speech emerged from the mouth of the hearing invisible, yet had substance? How did sound travel invisibly through the equally invisible air to enter the hearing ear, where it rushed over and caressed a billion tiny hairs deep in the ear canal, like sea grass waving tremulously to the un heard tune of invisible currents?

And the biggest mystery of all: How did the vibrations transmit sound to the mind, where it was

heard

?

His questions began when I was six years old. I could never answer them satisfactorily, and they would not cease until I left his deaf world forever, twelve years later, college-bound.

Once I was no longer a trusted resident of his world, merely a visitor, something changed between us and his questions ceased. Many years later I realized that with my departure, his unquenchable quest for the understanding of sound had ended; he had asked no more questions of me.

To this day, when I think of my father, and I recall so vividly the intensity of my childhood, I remember my uncle David’s birthday gift: the silver dollar.

Oh, how I wish I had saved it. I would set it spinning. What would it tell me now?

27

Death, a Stranger

I

knew of death early and late.

When I was six year sold, I saw a man standing on the edge of an apartment house roof on my block. He had been standing there for sometime, motionless, on the low brick wall that was the dividing line between the tar-papered, gravel-covered roof to his back and the air over Brooklyn at his feet. Staring straight ahead, he could see the Atlantic Ocean at Coney Island. Looking down, he could see the concrete sidewalk of West Ninth Street, six floors below his feet.