Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (19 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

At 6:00 a.m. I gave up and rolled up the blinds. Peering out into the canyon I saw a facelike shape in the dust-caked window across from me. It took a second to realize that it was in fact a human face, and it was staring at me. I pulled back and snapped the blind shut.

The place began to wear me down. It wasn’t so much the lack of view or light, or the filth in the canyon below. It was the feeling that I was never quite alone there. I would walk in and feel a simultaneous mix of claustrophobia and loneliness. It got worse when my family arrived for a visit, and every movement, sound, or scent in the cramped space had to be choreographed in order to avoid confrontation.

It struck me that the apartment was exactly the kind of place that first drove the exodus to suburbia. Of course my discomfort was trivial compared with the intense squalor and domestic crowding suffered in these places a century before (or, for that matter, still experienced in tenements from Kowloon to Kolkata). But the place drained the energy I needed to tackle Manhattan and shortened my patience for the crowds outside. I came to feel as hostile toward my neighbors as Randy Strausser was to his in Mountain House. I gained a new sympathy for people who flee to the edge of the city or live in motor homes parked in the Nevada desert, or for the

hikikomori

, the more than seven hundred thousand Japanese who have retreated entirely from society, remaining inside their homes. I felt like one of the rats that researchers forced into overcrowded cages back in the 1970s. Those rats forgot how to build nests. They forgot how to socialize. They eventually started eating their offspring.

This is the other great challenge posed by density: its central tensions are as much social as they are aesthetic.

In the 1940s Abraham Maslow famously drew a pyramid of needs to represent the hierarchy of human motivation. At the base of the pyramid were the basic physiological needs—hunger, thirst, and sexual desire. According to Maslow, once you are satisfied on that level, you move to the next. So once you are well fed, you start worrying about safety. And you don’t move on up to the things Carol Ryff talks about in her expansive definition of

eudaimonia

—love, esteem, and self-actualization—until you feel safe. In the modern city, it is not weather or predators that threaten us. For most people it is not hunger, either. It is other people who fill the air with noise; pollute the air we breathe; threaten to punch us, shoot us, steal from us, crowd us, interrupt us during dinner, or just plain make us uncomfortable. Although we are rarely at risk of being robbed or assaulted, exposure to too many people can literally be maddening.

For decades, psychologists believed that dense cities were socially toxic specifically because of their crowding. They found correlations between high population density and such psychosomatic illness as sleeplessness, depression, irritability, and nervousness. Indeed, people who inhabit residential towers, even those with views, report being more fearful, more depressed, and more prone to suicide than people living on the ground.

Being around too many strangers involves a stressful mix of social uncertainty and lack of control. The psychologist Stanley Milgram, who grew up in the Bronx, observed that people in small towns were much more helpful to strangers than were people in the big city. He attributed the difference to overload—the sheer crowdedness of cities creates so much stimulus that residents have to shut out the noise and objects and people around them in order to cope. City life, Milgram felt, demands a kind of aloofness and distance, so that crowding, while pushing us together physically, actually pushes us apart socially.

The evidence supports Milgram’s case. People who live in residential towers, for example, consistently tell psychologists that they feel lonely and crowded by other people

at the very same time

. Other studies reveal that people who feel crowded are less likely to seek or respond to support from neighbors. They withdraw as a coping strategy but are thus denied the benefits of social support. And if enough people withdraw often enough, as Milgram pointed out, noninvolvement with other people becomes a social norm: it’s simply inappropriate to bug your neighbors.

The Crowd, Moderated

This is not the outright condemnation of urban density that it might seem. Crowding is a problem of perception, and it is a problem of design that can be addressed, at least in part, by understanding the subtle physics of sociability.

First of all, it is critical to understand that human density and crowding are not the same thing. The first is a physical state. The second is psychological and subjective. An example from that most common locus of crowding, the public elevator: Everyone knows how awkward and occasionally claustrophobic a long elevator ride can be. But psychologists have found that merely altering your position inside an elevator full of people changes your perception and your emotional state. Stand right in front of the control panel, where you can select which floor to stop on, and you are likely to feel that the elevator is not only less crowded but bigger. All that really changes here is your sense of control.

We tolerate other people more when we know we can escape them. People who live in areas with crowded streets report feeling much better when they have rooms of their own to which they can retreat. There’s a correlation between societal happiness and the number of rooms per person: it’s not so much square footage that matters, but the ability to moderate contact with other people. But even people who live in crowded homes tend to feel okay if they can easily escape to a quiet public place.

*

We expend a great deal of effort insulating ourselves from strangers, whether it’s retreating to the edge of suburbia or adding more security features to our urban apartments. But this habit can deprive us of some of the most important interactions in life: those that happen in the blurry zone among people who are not quite strangers, but not quite friends.

The sociologist Peggy Thoits interviewed hundreds of men and women about the many social roles they played in life, from their positions as spouses, parents, and workers to lighter, more voluntary roles such as working as a school crossing guard. She discovered that the lighter relationships we have in volunteer groups, with neighbors, or even with people we see regularly on the street can boost feelings of self-esteem, mastery, and physical health, all contributors to that ideal state that Carol Ryff called “challenged thriving.” The uncomfortable truth is, our spouses and children and coworkers can wear us out. Life’s lighter, breezier relationships soothe and reassure us, specifically because of their lightness.

*

This leaves us with a conundrum. As Randy Strausser learned back in Mountain House, the detached house in distant dispersal is a blunt instrument: it is a powerful tool for retreating with your nuclear family and perhaps your direct neighbors, but a terrible base from which to nurture other intensities of relationships. Your social life must be scheduled and formal. Serendipity disappears in the time eaten up by the commute and in that space between car windshields and garage doors. On the other hand, life in places that feel too crowded to control can leave us so overstimulated and exhausted that we retreat into solitude. Either way, we miss out on the wider range of relationships that can make life richer and easier.

This is especially worrying as family size shrinks and more of us live alone than ever before. The archetypal 1950s nuclear family, with mother and father raising two-point-something children, is no longer the norm. The average household size in the United States has shrunk to 2.6 people (2.5 in Canada and 2.4 in the United Kingdom). More people now live alone, commute alone, and eat alone than ever before. In fact, the most common household in the United States now consists of someone living

all alone

,

†

which happens to be the state most associated with unhappiness and poor mental health.

What we need are places that help us moderate our interactions with strangers without having to retreat entirely.

Testing Proximity

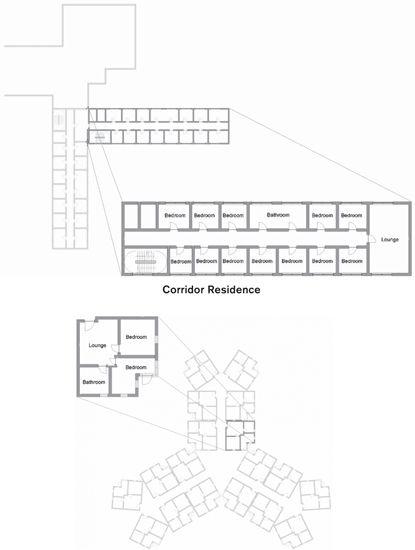

The good news is that the crucial blend of control and conviviality can be designed into residential architectures. A hint of this first emerged in a stunning 1973 study in which psychologist Andrew Baum compared the behavior of residents of two starkly different college dormitories at Stony Brook University in Long Island, New York. In one residence, thirty-four students lived in double bedrooms along a single long corridor—a bit like a hotel, except that they shared one large bathroom and a lounge area at the end of the hallway. The other building housed just as many students, but the floors were broken up into suites, with two or three bedrooms each, sharing a lounge and a small bathroom. All the students were randomly assigned, but their reaction to their environment was far from random.

The students who lived in the corridor block felt crowded and stressed out. They complained about unwanted social interactions. The problem was that the long-corridor design made it almost impossible for them to choose whom they bumped into and how often. There was no in-between space. You were either in your room or out in the public zone of the hallway.

The design didn’t merely make the students irritated. It changed the way they treated one another. The corridor residents did not become friends. The suite residents did. The corridor residents were less helpful to one another. They actually avoided one another, and they grew more antisocial as the year progressed.

Amazingly, the students carried their behavior with them to other parts of their lives. At one point the students were called to an office and asked to wait for an appointment along with one of their neighbors. Unlike the corridor residents, the suite residents chatted and made eye contact with each other. They reassured each other. They sat closer together.

*

How does this tension between conviviality and sense of control translate into built form for those of us who do not live in university dormitories?

Suite Residence

Friendlier by Design

Students who lived in suite residences where they could control social interactions (

bottom

) experienced less stress and built more friendships than students who lived along long corridors (

top

).

(Valins, S., and A. Baum, “Residential Group Size, Social Interaction, and Crowding,”

Environment and Behavior,

1973: 421; redesign by David Halpern and Building Futures)

The high modernist past offers a lesson. The most spectacular and symbolic failure was Minoru Yamasaki’s thirty-three-block Pruitt-Igoe housing complex, built in 1950s St. Louis. The project was an attempt to revive a poverty-stricken inner-city neighborhood by replacing ramshackle row houses and tenements with rows of pristine, identical apartment blocks in a sea of lawn. Yamasaki’s architectural drawings featured mothers and children frolicking in common galleries and in parklike spaces that separated the buildings. But the complex grew infamous for squalor, vandalism, drug use, and fear. Nobody used the generous lawns between the buildings. Nobody felt safe.

The architect Oscar Newman toured Pruitt-Igoe at the height of its dysfunction, and he found landscapes of social health that directly corresponded to design: “Landings shared by only two families were well maintained, whereas corridors shared by 20 families, and lobbies, elevators, and stairs shared by 150 families were a disaster—they evoked no feelings of identity or control.” In the shared decks of those towers and the vast featureless grounds between the buildings, Newman observed a dysfunction he famously termed indefensible space: where nobody felt ownership over common space, garbage piled up, vandalism took hold, and the landscape was left to drug dealers. After two decades, two-thirds of its flats were abandoned. Although it is true that the community was beleaguered with the problems of poverty and shabby management, design mattered: the Pruitt-Igoe meltdown stood in wild contrast to a row-house project across the street, where people of similar background managed to take care of their environment right through Pruitt-Igoe’s worst years. The St. Louis Housing Authority began dynamiting Pruitt-Igoe in 1972.

It must be said that reports of unhappy tower living tend to be skewed by the particular interests of social science researchers. After comparing hundreds of human density studies, David Halpern noted that most of them focused on social housing or slums from the most crowded urban areas in the world, places that tended to be inhabited by desperately poor people with fewer resources. In other words, they were surveying people whose difficult life circumstances would naturally make them less happy. We are now learning that the effect of density is nuanced. For one thing, wealthier people do better in apartment towers than poor people. Not only do they have the money to pay for concierges, maintenance, gardening, decoration, and child care, but, having chosen their residences, they tend to attach greater status to them. Home feels better when it carries a different message about who you are. (A building’s status can be altered without any physical change at all. When they were sold on the open market, once-despised social housing blocks in central London became objects of desire for middle-class buyers who fetishized their retro modernism.)