Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (23 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

When you think about it, none of this crowd affinity should be a surprise. Almost all of us will choose a seat in a restaurant with a view of others. People will show up for the most mundane small-town parades. We like to look at each other. We enjoy hovering in the zone somewhere between strangers and intimates. We want the opportunity to watch and be watched, even if we have no intention of ever actually making contact with one another.

Streets for People

Copenhagen’s Strøget before and after pedestrianization

(Jan Gehl and Lars Gemzøe / Gehl Architects Urban Quality Consultants)

This hunger for time among strangers is so widespread that it seems to contradict the urge to retreat that helped create the dispersed city in the first place.

The Stranger Deficit

Places like the Strøget carry an increasingly urgent message about the role of public life in cities. For thousands of years, city life naturally led people toward casual contact with people outside of our circle of intimates. In the absence of refrigeration, television, drive-thru, and the Internet, our forebears had no choice but to come together every day to trade, to talk, to learn, and to socialize on the street. This was the purpose of the city.

But modern cities and affluent economies have created a particular kind of social deficit. We can meet almost all our needs without gathering in public. Technology and prosperity have largely privatized the realms of exchange in malls, living rooms, backyards, and on the screens of computers and smartphones. We can enjoy the cinema without leaving bed. We can build new friendships without regard for geography. We tweet our gossip or argue on Facebook walls. We peruse and interview prospective love interests online. We have gotten so good at privatizing our comforts, our leisure time, and our communication that urban life gets scoured of time with people who are not already colleagues, family, or close friends. Tellingly, the word

community

is increasingly used to refer to groups of people who use the same media or who happen to like a certain product, regardless of whether its members have actually met.

As more and more of us live alone, these conveniences have helped produce a historically unique way of living, in which home is not so much a gathering place as a vortex of isolation.

So far, technology only partially makes up for this solitude. Television, that great window to the world, has been an unequivocal disaster for happiness. The more TV you watch, the fewer friendships you are likely to have, the less trusting you become, and the less happy you are likely to be.

*

The Internet has been a mixed blessing. If you use your computer, iPad, or mobile device much like TV, it has the same negative effect on you as TV. If you use your devices to interact with people, they can help support your close relationships—one study found that after the introduction of an online discussion list in several Boston communities, neighbors actually started sitting out on their porches and inviting each other to dinner more. But our electronic tools are not good enough on their own. A growing stack of studies provide evidence that online relationships are simply not as rich, honest, or supportive as the ones we have in person. (One example: People are more likely to lie to each other when texting than when standing beside each other. But you already knew

that

, didn’t you?) The primacy of face-to-face interactions is nothing new. We have spent thousands of years basing our interactions on all our senses: we use not just our eyes and ears, but our noses to receive subtle signals about who people are, what they like, and what they want. There is simply no substitute for

actually being there.

*

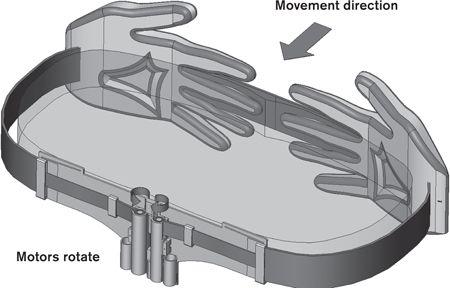

HaptiHug Telecuddle Interface

This vest concept, part of Keio University Tachi Lab’s iFeel IM! system for feeling enhancement, translates the emotions of a distant communicator into a physical hug. The goal, according to creators, is to create “an emotionally immersive experience” in 4-D. Can we ever fully replicate the sensation of actually meeting in person?

(Courtesy of Dzmitry Tsetserukou, EIIRIS, Toyohashi University of Technology)

In an age obsessed with virtual space, the quest for conviviality ultimately brings us back to the physical realm. The question remains: Can we build—or rebuild—city spaces in ways that enable easy connnections and more trust among both familiars and strangers? The answer is a resounding yes. The spaces we occupy can not only determine how we feel. They can change the way we regard other people and how we treat one another.

A Science of Conviviality

The great sociologist Erving Goffman suggested that life is a series of performances in which we are all continually managing the impression we give other people. If this is so, then public spaces function like a stage in the same way that our own homes and living rooms do. Architecture, landscaping, the dimensions of the stage, and the other actors around us all offer cues about how we should perform and how we should treat one another.

A man might urinate in a graffiti-covered alleyway, but he would not dream of doing so in the manicured mews outside an old folks’ home. He would be more likely to offer a kindness in an environment where he felt he was among family or friends, or being watched, than in some greasy back alley. In Goffman’s world, these are conscious, calculated responses to the stage setting. But recently we have learned that some of our social responses occur even without conscious consideration. Like other animals, we have evolved to assess risks and rewards in the landscapes around us unconsciously.

The evolutionary biologists D. S. Wilson and Daniel O’Brien showed a group of nonresidents pictures of various streetscapes from Binghamton, New York. Some of those streets featured broken pavement, unkempt lawns, and dilapidated homes. Others featured crisp sidewalks and well-kept yards and homes. Then the volunteers were invited to play a game developed by experimental economists in which they were told that they would be trading money with someone from the neighborhood they had viewed. You probably already know how they behaved: the volunteers were much more trusting and generous when they believed they were facing off with someone from the tidier, well-kept neighborhood. You might consider this a logical response to clues about each neighborhood’s social culture—tidiness conveys that people respect social norms, for example. But even the quality of the pavement—which bore no real relationship at all to the trustworthiness of a street’s residents—influenced them.

In fact, we regularly respond to our environment in ways that seem to bear little relation to conscious thought or logic.

For example, while most of us agree that it would be foolish to let the temperature of our hands dictate how we should deal with strangers, lab experiments show that when people happen to be holding a hot drink rather than a cold one, they are more likely to trust strangers. Another found that people are much more helpful and generous when they step off a rising escalator than when they step off a descending escalator—in fact, ascending in any fashion seems to trigger nicer behavior.

*

Psychologists stretch themselves trying to explain these correlations. One theory suggests that we experience environmental conditions as metaphors: thus we would translate physical warmth as social warmth, and we would feel an elevated sense of ethics or generosity by gaining elevation. Another line of inquiry known as terror management theory posits that we are all motivated by a constant underlying fear of death. By this way of thinking, those cracked sidewalks in Binghamton would trigger unconscious fears that would cause us to retreat from the people who lived there. Whatever the mechanism, what is certain is that the environment feeds us subtle clues that prime us to respond differently to the social landscape—even if those clues are wholly untethered from any rational analysis of our surroundings.

Neuroscientists have found that environmental cues trigger immediate responses in the human brain even before we are aware of them. As you move into a space, the hippocampus, the brain’s memory librarian, is put to work immediately. It compares what you are seeing at any moment to your earlier memories in order to create a mental map of the area, but it also sends messages to the brain’s fear and reward centers. Its neighbor, the hypothalamus, pumps out a hormonal response to those signals even before most of us have decided if a place is safe or dangerous. Places that seem too sterile or too confusing can trigger the release of adrenaline and cortisol, the hormones associated with fear and anxiety. Places that seem familiar, navigable, and that trigger good memories, are more likely to activate hits of feel-good serotonin, as well as the hormone that rewards and promotes feelings of interpersonal trust: oxytocin.

“The human brain is adaptive, and constantly tuning itself to the environment it is in,” the neuroeconomist Paul Zak told me the day I met him in Anaheim, California. Zak is the researcher who discovered the key role that oxytocin plays in mediating human relationships. Unlike some more solitary mammals, Zak explained, humans have a huge concentration of oxytocin receptors in the oldest parts of our brain, which can kick into gear even before we have started talking to people.

This should be a concern for city makers because, as much as we are drawn to other people, neither culture nor biological mechanisms ensure that we will always treat strangers well. For example, Dutch researchers found that oxytocin, which should reward us for engaging in cooperative or altruistic behavior, has what might be called a xenophobic bias. After puffing a synthetic version of oxytocin, Dutch students were offered the standard moral dilemma question: Would you throw someone in front of a train if doing so would save five other lives? Exposure to the oxytocin made the students less likely to toss someone with a traditional Dutch name in front of the train, but

more likely

to sacrifice someone whose name sounded Muslim. Such anti-cosmopolitan tribalism can seem depressing until you consider the miracle of trust and cooperation that great cities, and especially great public places, can foster. Design can prime us toward trust and empathy, so that we regard more people as worthy of care and consideration.

To demonstrate this idea, Zak took me for a walk down Southern California’s most convivial street, which, in a sad commentary on the state of American public space, sits beyond the fare gate at the entrance to Disneyland.

We crossed under the berm that surrounds the theme park, traversed the faux town square with its veranda-fronted city hall, then paused midway down Main Street U.S.A., that simulacrum of ultrahappy urbanity. The place was full of people of all ages and races, pushing strollers, walking hand in hand, window-shopping, and taking photos among the arcades and eateries.

We inserted some incivility into that crowd. At Zak’s urging, I leaned my shoulder toward passing bodies, first brushing passersby, then making full contact. It was just the kind of behavior that would get you slugged on other streets, but time and again I got a smile, a steadying hand, or an apology. I tried dropping my wallet several times and got it back every time with an enthusiasm that bordered on the ceremonial. Then we upped the ante. We accosted random strangers and asked them for hugs. This was a bizarre request from two grown men, but the Main Streeters, men and women, responded with open arms and little hesitation. The place displayed a pro-social demeanor that was almost as cartoonish as the setting.

There are many reasons for the cheeriness on Disney’s Main Street U.S.A., not least of which is the fact that people go there intending to be happy. But Zak encouraged me not to ignore the powerful priming effects of the landscape around us. No storefront on this Main Street is more than three stories high, but those unused top floors play a visual trick. They have been shrunk to five-eighths size, giving the buildings the comfortable, unthreatening aura of toys. Meanwhile, from the striped awnings and gilded window lettering to the faux plaster detailing on each facade, every detail on the artificial street is intended to draw you deeper into a state of nostalgic ease.

*