Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (10 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

High-minded observers were convinced that the urban landscape was corrupting not just the health but also the minds and the very souls of its inhabitants. How would they be rescued? Was the solution to tinker with the city, abandon it, or kill the monster and replace it with a grand, new vision of urbanity? Their proposals ran the gamut, but two design ideologies from those miserable years went on to shape cities right through the twentieth century, and they have driven architects, reformists, and politicians ever since. They seeped into the culture. This is what gave them power.

The first philosophy might be called the school of separation. Its central belief is that the good life can be achieved only by strictly segregating the various functions of the city so that certain people can avoid the worst of its toxicity.

The other we might call the school of speed. It translates the lofty concept of freedom into a matter of velocity—the idea being that the faster you can get away from the city, the freer you will become.

As I explained in Chapter 2, cities have always been shaped by powerful beliefs about happiness. But no philosophies have transformed cities and the world so fully as these.

Everything in Its Place

First, consider the evolution of the idea of separation, which was a natural response to the horrors of the Industrial Revolution. With crowded cities choking on soot and sewage, it was reasonable to wish to retreat from—or at least isolate—the city’s unpleasantness. This was the aspiration behind Ebenezer Howard’s plans for garden cities, which promised lungfuls of fresh air and conviviality for Londoners who could afford to retreat to their semirural setting. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City plan promised nothing less than

spiritual

redemption for the tenement dweller who would lead his family away from the gothic verticality of Manhattan. In Europe, the modernists’ response was similarly motivated by a horror of the city, but it was much more optimistic. Inspired by almost supernatural advances in technology and the mass-production techniques employed by such industrial pioneers as automaker Henry Ford, they imagined that cities could be fixed by rebuilding them in the image of highly efficient assembly lines. “We claim, in the name of the steamship, the airplane, and the automobile, the right to health, logic, daring, harmony, perfection,” Le Corbusier wrote. “We must refuse to afford even the slightest concession to what is: to the mess we are in now … there is no solution to be found there.”

I suggested earlier that Le Corbusier’s happiness formula was a matter of geometry and efficiency. But his ethos was just as separationist as that of his American counterparts: he believed that most urban problems could be fixed by separating the city into functionally pure districts arranged according to the simple, rational diagrams of the master architect. Le Corbusier’s Radiant City plan exhibits this philosophy in all its wondrous simplicity: on this quadrant are the machines for living; on that quadrant, the factory zone; on another, the district for shopping—urban units stacked neatly like packages you might see in an IKEA warehouse.

These days such geometrically pure separatist schemes have lost much of their health-related raison d’être. With the help of emission controls and sewage systems, city centers in most advanced economies are no longer toxic, at least in the physical sense. But the ideology of separation has lived on, and nowhere so vividly as in American suburban dispersal. The most casual glance at any contemporary suburban plan, including those that define the territory of the Repo Tour, will reveal a simple set of land uses numbered, color-coded, and laid across the landscape with a paint-by-numbers artfulness best interpreted from thirty thousand feet.

The typical dispersed sprawl plan seems at first to be a fusion between the escapist’s garden city and the modernist’s perfectly segregated machine idyll. How did such rigid, centrally planned schemes find life in libertarian America? Well, the path that led from the utopias of a century ago to today’s sprawl was not straight. It meandered back and forth between pragmatism, greed, racism, and fear.

Americans do not like to think of themselves as a people who easily accept grand plans imposed from above. But they have been just as willing as Canadians, British, and Europeans to support rules that restrict their property rights. In the 1880s, lawmakers in the California city of Modesto introduced a new law banning laundries and washhouses (which all happened to be run by Chinese) from the city core. Later, retailers in Manhattan demanded that properties be zoned to keep industrial interests from sullying the shopping areas along Fifth Avenue. In 1916 the city did just that. Hundreds of municipalities followed. Zoning was intended to reduce congestion, improve health, and make business more efficient. But most of all, it protected property values. Perhaps this is why we so enthusiastically embraced it.

Not that there wasn’t pushback. A local real estate developer took the village of Euclid, Ohio, to court to stop it from using zoning to block his industrial aspirations in 1926. That fight went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The village won, and shortly thereafter, the federal government gave all municipalities the same power. Since then, it has been illegal in most American jurisdictions to deviate from very narrow sets of rules governing how cities should be built or altered. Zoning laws and development codes specify what you can build and what you can do on your land. They specify the dimensions of lots, setbacks, and houses long before any of us gets a chance to move to a new neighborhood. Most powerfully, they strictly separate places for living, working, shopping, and recreation. Functional segregation was built into almost every new suburb after World War II.

The separatist project was quickened by massive subsidies in the form of federal mortgage insurance programs that favored new suburban home projects over renovations or inner-city development. You couldn’t get a mortgage for a “used” house in many older neighborhoods even if you wanted to live there. You had to move to something new on the edge.

This project was also fueled by fear: not just fear of the noise, fumes, and dirt of industry, but fear of exposure to other people. It is impossible to decouple America’s suburban spread from race and class tension. Racial segregation was de facto federal policy for years. The U.S. Federal Housing Administration, which appraised neighborhoods, regularly excluded entire black communities from mortgage insurance until the advent of civil rights legislation in the 1960s. The policy gutted inner cities, while “white flight” fueled layer after layer of new suburban dispersal. So-called exclusionary zoning, which on the surface bans only certain kinds of buildings and functions from a neighborhood, served the deeper purpose of excluding people who fall beneath a certain income bracket. The tactic still works today. If you want to keep poor people out of your community, all you really need to do is ban duplexes and apartment buildings—which is exactly what new suburbs were permitted to do. The urban strategist Todd Litman summed up zoning’s effect thus: “It seemed that segregation was just the natural working of the free market, the result of the sum of countless individual choices about where to live. But the houses were single—and their residents white—because of the invisible hand of government.”

What’s amazing is how, despite their love of liberty, Americans have embraced the massive restriction of private property rights that the separated city demands. Once a neighborhood is zoned and built, it gets frozen like a Polaroid from the day everyone moves in. As if the power of municipal zoning wasn’t enough, suburban developers in the last few decades have set up homeowner associations that encourage residents to exert even more control over one another. Thus, an allegedly government-hating people have embraced an entirely new layer of government.

The color bar is not as visible now in exurban San Joaquin County, but retreatist reassurance can still be seen in the homeowner association rule books that dictate exactly what you can and cannot do with your property. Repo tourists beware: Stockton’s Brookside West Owners’ Association has a bylaw requiring owners to keep their lawns groomed to standards set by the association board. It’s the same across the country: anyone who tries to add a suite in the basement or convert a garage into a candy store or grow wheat in a front yard learns this quickly enough. Even if you do not live in a homeowner association–controlled community, all it takes is one complaint for city inspectors to descend and remind you that your home really is not your castle.

It’s important to point out that the ethos of spatial separation favored large-scale retailers and ambitious suburban property developers who find it easier and cheaper to impose simple designs on large parcels of virgin land than to adapt to existing urban fabric. These interests lobbied successfully for decades for tax incentives from governments hungry for new business, a story I’ll return to in Chapter 12.

Suburban zoning and development codes grew so powerful and so entrenched by the end of the twentieth century that the people who financed and built most of suburbia had all but forgotten how to make anything but car-dependent sprawl. “We have not had a free market in real estate for eighty years,” Ellen Dunham-Jones, Georgia Tech professor of architecture and coauthor of

Retrofitting Suburbia

, told me. “And because it is illegal to build in a different way, it takes an immense amount of time for anyone who wants to do it to get changes in zoning and variance. Time is money for developers, so it rarely happens.”

Tampa, Florida: The City as Simple Machine

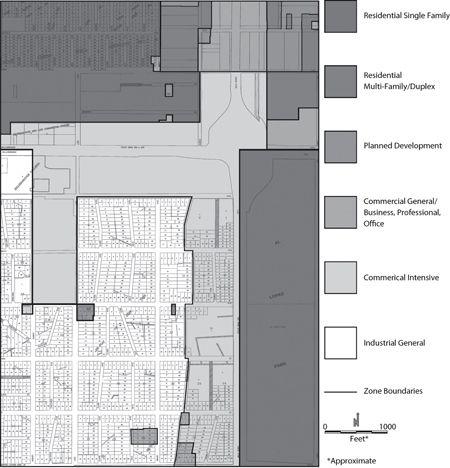

The ideology of separation lives on in American suburban plans. This zoning map of Tampa reveals a strikingly simplistic set of zones that restrict exactly what can be built—and what can happen—everywhere. Although these systems are easy for planners to understand, they ban complexity and restrict freedom.

(Cole Robertson/City of Tampa)

Together, these rules and habits have ensured that the American city is as separated and as static as any Soviet-era housing scheme. They have ensured that first-generation suburbs closer to downtowns do not grow more diverse or dense. They have pushed new development out to the ever-expanding urban fringe and beyond. They are part of the reason that housing supply is so tight in the San Francisco Bay Area that hundreds of thousands of area workers like the Strausser clan are forced to drive two hours north, south, or east. And they have ensured that these new developments will, in turn, resist most efforts to change or adapt them over time.

When Freedom Got a New Name

This reorganization of cities could not have happened without breathtaking subsidies for roads and highways, a decades-long program that itself required a cultural transformation, with roots in a concept that Americans hold especially dear. A century ago, Americans redefined what it meant to be free in cities.

For most of urban history, city streets were for everyone. The road was a market, a playground, a park, and yes, it was a thoroughfare, but there were no traffic lights, painted lanes, or zebra crossings. Before 1903 no city had so much as a traffic code. Anyone could use the street, and everyone did. It was a chaotic environment littered with horse dung and fraught with speeding carriages, but a messy kind of freedom reigned.

Cars and trucks began to push their way into cities a few years after Henry Ford streamlined the mass production process at his automobile assembly line in Highland Park, Michigan. What followed was “a new kind of mass death,” says urban historian Peter Norton, who charted the transformation in America’s road culture during the 1920s. More than two hundred thousand people were killed in motor accidents in the United States that decade. Most were killed in cities. Most of the dead were pedestrians. Half were children and youths.

Last Days of the Shared Street

Woodward Avenue, Detroit, circa 1917: When streetcars and private automobiles moved slowly, everyone shared the street. Speed—and a concerted effort by automobile clubs and manufacturers over the next decade—changed the dynamic forever.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection)