Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (12 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

To determine what those redesigns might look like, we need to understand how places, crowds, views, architecture, and ways of moving influence the way we feel. We need to identify the unseen systems that influence our health and control our behavior. Most of all, we need to understand the psychology by which all of us comprehend the urban world and make decisions about our place in it.

5. Getting It Wrong

“You see, happiness ain’t a thing in itself—it’s only a contrast with something that ain’t pleasant … And mind you, as soon as the novelty is over and the force of the contrast dulled, it ain’t happiness any longer, and you’ve got to get up something fresh.”

—Mark Twain, “Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven”

“Nothing in life is quite as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it.”

—Daniel Kahneman

There is a particularly vexing problem on the road to the happier city, and it travels with every one of us. The emerging consensus among psychologists and behavioral economists is that as individuals and as a species, humans just aren’t that well equipped to make decisions that maximize our happiness. We make predictable mistakes when deciding where and how to live, and the architects, planners, and builders who create the landscapes that help shape our decisions are prone to some of the very same mistakes. I became aware of this at an especially inconvenient moment.

I was born in Vancouver, the city wedged between sea and forested mountains on the west coast of Canada, which regularly tops lists of the world’s most livable cities. The setting is gorgeous. Fresh air, mild climate, and rain forest views attract retirees, investors, and part-time residents from around the world. All this has made Vancouver a high-value, high-status destination whose charms are reflected in its soaring real estate prices.

Like many people born in the 1960s, I could not imagine spending my adult life in some generic apartment. I wanted a house and my own piece of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “good ground.” I did not base this wish on any particular utilitarian calculation. I was just certain I would be happier once I had achieved it. So in 2006, when the average price of a detached home in Metro Vancouver hit $520,000,

*

I bought a share of an old friend’s house, a two-story fixer-upper on the city’s working-class East Side.

The house was perfectly habitable, but it did not resemble the ones pictured in the home and garden magazines that my co-owner, Keri, collected. The place was cut through with awkwardly angled walls and floored with barbershop checkerboard linoleum. The century-old timber frame swayed and lurched in time with any romance conducted on the top floor. It was a little too dark, a little too drafty, and, we decided, a little too cramped. So we signed papers on a second mortgage in order to raise that creaking frame, strip it down to the studs, and transform the place into the home of our dreams. We figured that nine-foot ceilings, reconditioned fir floors, an open-plan kitchen, two living rooms, an extra story, and a couple of extra bathrooms should do it. Like millions of our fellow middle classers, we were sure that the extra square footage would make us happier, despite the quarter-million dollars we had to borrow to get us there. We pictured ourselves sipping wine under blown-glass pendant lights while summer breezes wafted in from the patio.

Construction began the next spring. No sooner had the house been severed from its foundations and propped on story-high columns of railway ties than I was broadsided by the first warning about the psychological trap we had fallen into. This realization arrived by way of Nants Foley, a Realtor in the California town of Hollister. Foley had just written an emotional column that appeared in the Hollister

Pinnacle

warning homebuyers to be wary of the urge to follow their dreams. Foley’s own clients invariably wanted to trade up: they all wanted a bigger house on a bigger yard in a more perfect neighborhood, and Foley helped them get it. But after a few sales cycles she noticed that those big homes did not seem to be making her clients happier. “Time and again,” she told me when I called her, “I would walk into an absolutely gorgeous home with a beautiful pool that never got used and a game room that was never actually filled with friends, owned by people who were living really unhappy lives.”

People’s new homes were so big that they created a whole new layer of housekeeping, and so expensive that they forced their owners to work harder to keep them. One day Foley joined a Realtors’ tour of a spacious stucco tract home. The walls were pristine—Foley still remembers the color: Navajo Sand. The carpets were immaculate. But the place felt like a campsite. There was practically no furniture. A lone TV sat on a packing crate, and just about everything else lay on the floor. Clothing, books, and tools, all stacked in neat piles. Mattresses and futons lined the carpets in the bedrooms. It was clear that the house purchase had taken the family right to the edge of its financial wherewithal. They had spent everything they had. There was nothing left for furniture or garden supplies. The yard was a mud pit. The family had joined the ranks of what Foley called “floor people,” since floor space was all they had.

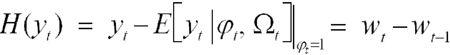

How was it that so many people had made decisions that led them into hardship? Foley found her answer in a treatise by the Nobel Prize–winning economist Gary Becker and his colleague Luis Rayo at the University of Chicago. The pair had poured the latest findings in psychology, evolutionary theory, and brain science into an algorithm that describes a trap that the economists believe is endemic to our species. Here it is:

Dubbed the evolutionary happiness function, the equation explains the psychological process that both fuels our desire for bigger homes and ensures that we will be dissatisfied shortly after moving in. Dissatisfaction, it suggests, is inevitable. Considering my own rapidly expanding home, I called Rayo in a panic.

He explained that the equation’s message is simple:

Humans do not perceive the value of things in absolute terms. We never have. Just as our eyes process the color and luminosity of an object relative to its surroundings, the brain constantly adjusts its idea of what we need in order to be happy. It compares what we have now to what we had yesterday and what we might possibly get next. It compares what we have to what everyone else has. Then it recalibrates the distance to a revised finish line. But that finish line moves even when other conditions stay the same, simply because we get used to things. So happiness, in these economists’ particular formulation, is inherently remote. It never stands still.

Framed this way, the happiness function would have served our prehistoric ancestors really well. Hunter-gatherers more oriented to dissatisfaction, those who compulsively looked ahead in order to kill more game or collect more berries than they did yesterday, were more likely to make it through lean times and thus pass on their genes. In this model, happiness is not a condition at all. It is an urge genes employ to get an organism working harder and hoarding more stuff. The human brain has not changed much in the ten thousand years since we began to farm. We have been hardwired for active dissatisfaction.

“We are still slaves to that evolutionary hunting strategy,” Rayo insisted. “We are always comparing what we have to something else. But we’re not anticipating that no matter what we have, we will

always

be comparing it to something else. In fact, we’re not even aware that we are doing this. But there’s a difference between what’s natural and what’s good for us.”

Indeed, this trait does not serve the city dweller well, at least not in rich countries. The desire for marble countertops, stainless steel fixtures, and conspicuous purchases clearly doesn’t boost the likelihood that we will pass on our genes, and these things cannot, on their own, propel us any closer toward the horizon of shifting satisfaction.

Rayo assured me that it would be a matter of months before I started to compare my own renovated home to a new ideal.

Nants Foley handed in her Realtor’s lockbox and turned to farming in 2009.

I, meanwhile, was left with my expanding house and mortgage, and an uncertain place on the spectrum of shifting aspirations.

Wrong Again

Neoclassical economics, which dominated the second half of the twentieth century, is based on the premise that we are all perfectly well equipped to make choices that maximize utility. The discipline’s proverbial “economic man” has access to every piece of relevant information, doesn’t forget a thing, evaluates his choices soberly, and makes the best possible decision based on his options.

But the more psychologists and economists examine the relationship between decision making and happiness, the more they realize that this is simply not true. We make bad choices all the time. In fact we screw up so systematically that you might as well call behavioral economics the science of getting it wrong. Even when we do get complete information, which is rare, we are prone to a barrage of predictable errors of bias and miscalculation. Our flawed choices have helped shape the modern city—and consequently, the shape of our lives.

Take the simple act of choosing how far to travel to work. Aside from the financial burden, people who endure long drives tend to experience higher blood pressure and more headaches than those with short commutes. They get frustrated more easily and tend to be grumpier when they get to their destination.

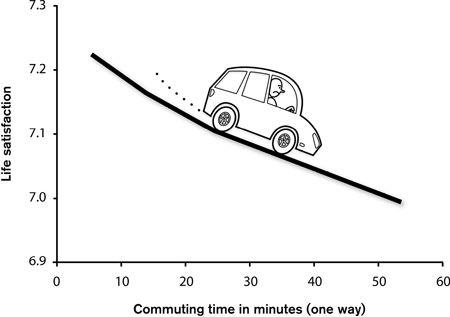

Anyone with faith in economic man would think that people would put up with the pain of a long commute only if they enjoyed even greater benefits from cheaper housing or bigger, finer homes or higher-paying jobs. They would weigh the costs and benefits and make sensible decisions. A couple of University of Zurich economists discovered that this simply isn’t the case. Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer compared German commuters’ estimation of the time it took them to get to work with their answers to the standard well-being question: “How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?”

Their finding was seemingly straightforward: the longer the drive, the less happy people were. Before you dismiss this as numbingly obvious, keep in mind that they were testing not for

drive

satisfaction, but for

life

satisfaction. So their discovery was not that commuting hurt. It was that people were choosing commutes that made their entire lives worse. They simply were not balancing the hardship of the long commute with pleasures in other areas of their lives—not through higher income nor through lower costs or greater enjoyment of their homes. They were not behaving like economic man.

This so-called commuting paradox blows a hole in the long-accepted argument that the free choice of millions of commuters can sort out the optimal shape of the city. In fact, Stutzer and Frey found that a person with a one-hour commute has to earn 40 percent more money to be as satisfied with life as someone who walks to the office. On the other hand, for a single person, exchanging a long commute for a short walk to work has the same effect on happiness as finding a new love.

*

Yet even when people were aware of the harm their commutes did to their well-being, they did not take action to rearrange their lives.

One human characteristic that exacerbates such bad decision making is adaptation: the uneven process by which we get used to things. The satisfaction finish line is actually more like a snake than a line. Some parts of it move away as we approach, and some do not. Some things we adapt to quickly and some things we just never get used to. Daniel Gilbert, Harvard psychologist and author of

Stumbling on Happiness

, explained the commuting paradox to me this way:

“Most good and bad things become less good and bad over time as we adapt to them. However, it is much easier to adapt to things that stay constant than to things that change. So we adapt quickly to the joy of a larger house because the house is exactly the same size every time we come in the front door. But we find it difficult to adapt to commuting by car, because every day is a slightly new form of misery, with different people honking at us, different intersections jammed with accidents, different problems with weather, and so on.”

It would help if we could distinguish more broadly between goals that offer lasting rewards and those that do not. Psychologists generally divide the things that inspire people to action into two groups: extrinsic or intrinsic motivators.

As the name suggests, extrinsic motivators generally come with external rewards: things we can buy or win, or things that might change our status in the world. But while a new granite countertop or an unexpected pay raise makes you happier in the short run, these changes don’t do much for long-term happiness. Most of the boost you feel from a leap on the income ladder simply evaporates within a year. The finish line shifts.