Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (4 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Private glory trumped public good. For every marbled

domus

, there were twenty-six blocks of cramped tenements. Although Julius Caesar tried to rationalize these slums by imposing height limits and fire regulations, life among the tenements was harsh. The narrow streets were filled with refuse, and the noise was constant. Entire apartment buildings collapsed with frequency. As faith in and affection for the city withered, public architecture and spectacle were put to work to placate the increasingly rebellious lower classes. Massive baths, shopping opportunities (including Trajan’s five-story

mercato

, the world’s first mall), bloody gladiator battles, circuses, and displays of exotic animals were the tools of distraction.

Where the Athenian philosophers had championed the spiritual life of the polis, the Romans gradually came to be disgusted by city life. Rome’s greatest poet, Horace, fantasized about returning to a simple farming existence.

*

Foreshadowing a twentieth-century trend, the patrician elite retreated to their villas in the countryside or on the Bay of Naples.

As the Roman Empire declined, urban well-being across Europe was reduced to the essentials of security and survival. Happiness, if you could call it that, came to be embodied by two architectures. In the early Middle Ages, no city could survive without walls. But just as essential was the cathedral, which made an entirely unique promise regarding happiness.

Like cities since the beginning of urbanity, Christian and Muslim communities in the former Roman territories positioned their sacred architecture at the heart of urban life. Islam forbade representations of the sacred image, but the Christian church embodied its faith story in form. The cathedral’s footprint in the shape of the cross alluded specifically to the suffering of Christ. But inside, architecture offered a means to transcend worldly pain. Medieval churches made use of high walls and vaulted ceilings so that every visitor would have a personal experience of the Ascension. Even today, if you stand inside Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral, your eye will inevitably be drawn higher and higher until it reaches an inner roof above the nave. As Richard Sennett once pointed out, it is a journey all the way to the base of heaven. The message is clear: happiness awaits in the afterlife, not here on earth.

But the medieval church carried with it another message: that the anchor of the city, the place that gave it meaning and connected it to heaven, was public. Often churches were surrounded with open space delineating the shift from secular to sacred. Here, in the shadows of the church, is where babies were abandoned and plague victims tolerated. Here is where you could beg for help if you were desperate. At the heart of the city—the transition zone between earth and heaven—was a promise of empathy.

Feeling All Right

Happiness, as expressed in philosophy and architecture, has always been a tug-of-war between earthly needs and transcendent hopes, between private pleasures and public goods. For centuries, Europeans put their faith in heavenly salvation. That changed in the Age of Enlightenment. A boom in wealth, leisure time, and longevity convinced eighteenth-century thinkers that happiness was both a natural and widely attainable state here on earth. Governments were obligated to promote happiness for everyone. Sure enough, in the fledgling United States, the Founding Fathers declared that God had endowed men with the unalienable right to pursue it.

But this happiness was nothing like the

eudaimonia

of ancient Greece.

The English social reformer Jeremy Bentham encapsulated the new approach to the concept in his principle of utility: since happiness was really just the sum of pleasure minus pain, he said, the best policy for governments and individuals on any given question could be determined by a straightforward act of mathematics, so as to maximize the former and minimize the latter. The obvious problem was figuring out how to measure the two.

Scholars of the Enlightenment liked nothing more than to take a scientific approach to social problems. Bentham was a man of his time, so he devised a complex set of tables called the felicific calculus, which gauged the amount of pleasure or pain any action was likely to cause. By adding up what he called “utils,” the calculus could be used to determine the utility of repealing laws against usury, or investing in new infrastructure, or even architectural designs.

*

But feelings stubbornly refused to submit to Bentham’s score sheet. He found it impossible to neatly calibrate the pleasure to be had from, say, a good meal, an act of kindness, or the sound of a piano, and he was therefore at a loss to find numbers to insert into equations that might produce the right prescriptions for living.

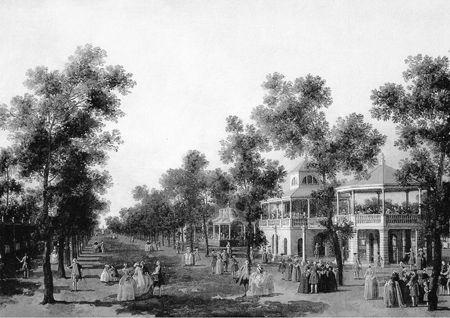

Regardless of the difficulty of measuring happiness, people still attempted to incorporate it into the architectures of the day. In London, Jonathan Tyers, an erstwhile leather merchant, transformed the walled Vauxhall Gardens south of the Thames into a leafy, pay-per-visit wonderland of outdoor portraits in rococo style, hanging lanterns, open-air concerts, and spectacle. The Prince of Wales visited, but so did anyone who could scrape up the modest one-shilling admission. Egalitarian hedonism ruled. Tightrope walkers entertained crowds of thousands, fireworks exploded, and mothers searched the garden’s verdant nooks for misbehaving daughters.

Vauxhall Gardens—The Grand Walk, c. 1751, by Giovanni Antonio Canal

During the Enlightenment, London’s premier pleasure garden, with its leafy promenades and performance pavilions, was a nexus of egalitarian hedonism, at a price even the masses could afford.

(From the Compton Verney Collection)

In France, Enlightenment ideals flowed through the public realm, through politics, and into revolution. The rulers of the Old Regime tightly censored print publications, so people traded news and gossip in parks, gardens, and cafés. When he inherited the sprawling Palais-Royal in Paris, Louis Philippe II, head of the House of Orléans and a supporter of the egalitarian ideals of Rousseau, threw open the gates to the complex’s lush private gardens and arcades. The Palais-Royal became a public entertainment complex populated by bookshops, salons, and refreshment cafés. It was a nexus of hedonic diversion, but also of philosophical and political foment. In the messy realm where public life, leisure, and politics collide, enlightened talk in the Palais-Royal about the right for all to enjoy happiness contributed to a revolution that would eventually see Louis Philippe II lose his head.

Moral Renovations

Since the Enlightenment, architectural and city planning movements have increasingly promised to nurture the mind and soul of society. Members of the City Beautiful movement were explicit in their assurances. Daniel Burnham, designer of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, proclaimed that beauty itself could reform society and conjure new virtue from citizens. His showpiece was a model city of gleaming white Beaux Arts monuments scoured clean of any signs of poverty. For the rest of central Chicago, Burnham proposed a City Beautiful: an overlay of grand avenues and elegant buildings that would restore to the city “a lost visual and aesthetic harmony, thereby creating the physical prerequisite for the emergence of a harmonious social order.” (He was much less clear about how the plan would provide for the poor who would be displaced to make room for the newly decorated city. Within weeks of the closing of the spectacular Columbian Exposition, thousands of workers were left unemployed and homeless, shut out of the now-empty hotels built for the Fair. Arsonists set fire to the fair’s remaining buildings.)

That faith in the power of architectural metaphor later found life on the far end of the political spectrum. Joseph Stalin’s reconstructions of postwar Eastern Europe in the style known as socialist realism were designed to exude power, optimism, and enough public elegance to assure people that they had made a collective status leap. You can still see remnants of that vision on Berlin’s Karl-Marx-Allee. The boulevard is so wide (almost 300 feet) that it feels completely empty without a full-on military parade. Its edges are populated with offices and once-elegant workers’ apartments whose facades, with their architectural ceramics, cupolaed towers, and statues helped them earn the descriptive moniker “wedding cake” half a century ago. If one ignores his sinister record, a walk down the boulevard might have one accepting Stalin’s proclamation: “Life has improved, my friends, life has become more cheerful. And when life is cheerful, it is easier to work hard.”

Others have tried to engineer the good society through sheer architectural efficiency. “Human happiness already exists expressed in terms of numbers, of mathematics, of properly calculated designs, plans in which the cities can already be seen!” declared the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, the high priest of the modern movement that emerged in Europe between the wars. In 1925 Le Corbusier proposed bulldozing much of the Right Bank in Paris and replacing the ancient neighborhoods of the Marais with a grid of superblocks on which would be arranged a series of identical sixty-story cruciform towers. That plan was never carried out, but Le Corbusier’s ideas were widely embraced by socialist governments, which used the modernist’s historically pristine approach to exert their new ideals on a grand scale across Europe.

Some modern reformers argued that the secret to happiness was to escape the city altogether. English reformers led by Ebenezer Howard planned utopian towns around train stations in the countryside.

*

In America, the advent of the automobile prompted innovators from Henry Ford to Frank Lloyd Wright to declare that liberation lay at the end of a highway. Private automobiles would free people to escape the central city to build their own self-sufficient compounds in a new kind of urban-rural utopia. In Wright’s planned Broadacre City, citizens would drive their own cars to all the means of production, distribution, self-improvement, and recreation that would be within minutes of their miniature homesteads. “Why should not he, the poor wage-slave, go forward, not backward, to his native birthright?” Wright wrote. “Go to the good ground and grow his family in a free city.” Together, technology and dispersal would produce true freedom, democracy, and self-sufficiency.

The pursuit of happiness has never delivered anything like Wright’s Broadacre City. Instead, it has led millions of people to detached houses with modest lawns—houses purchased with loans from huge financial institutions—far from employment, in the landscape now commonly known as suburban sprawl. This, the most common urban form in North America, has some roots in the American notions of independence and freedom that Wright espoused. But those roots go deeper, tapping into a particular way of thinking about happiness and the common good that reaches all the way back to the Enlightenment.

Buying Happiness

After Jeremy Bentham and his followers failed in their attempts to measure happiness, early economists seized on Bentham’s concept of utility, but they cleverly reduced his felicific calculus to something they could actually count. They could not measure pleasure or pain. They could not add up virtuous action or good health or long life or pleasant feelings. What they could measure was money and our decisions about how to spend it, so they substituted purchasing power for utility.

Broadacre City

A vision of extreme dispersal by Frank Lloyd Wright. The architect believed that highways—and, apparently, new flying machines—would set urbanites free to inhabit and work on their own autonomous plots in the countryside.

(Courtesy of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives [The Museum of Modern Art|Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York], © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ)

In his

Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

, Bentham’s contemporary Adam Smith warned that it was a deception to believe that wealth and comfort alone would bring happiness. But this didn’t stop his followers or the governments they advised from relying on the crude measures of income when measuring human progress over the next two centuries. As long as economic numbers grew, economists insisted that life was getting better and people were getting happier. Under this peculiar analysis, our estimation of well-being is actually inflated by divorces, car crashes, and wars, as long as those calamities produce new spending on goods and services.