Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (38 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Quality of life and climate action are complementary goals. It’s just easier to get people excited about plans that improve their lives. That’s why, when the City of New York explains its remarkable transformation in the way the city uses roads, it boasts about its huge improvements in safety, speed, efficiency, and people’s taking coffee on public plazas, leaving its goal of reducing the city’s greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent to a footnote.

Death and Taxes

Still, this focus on quality of life risks obscuring other, increasingly urgent synergies emerging between climate action and happy urban design. For one thing, public health researchers have discovered that designs that lower greenhouse gas emissions also make entire societies healthier.

The Lancet

, the prestigious British medical journal, argued that whether you are in London or Mumbai, interventions to make walking and cycling safe and comfortable are radically more effective at bringing down emissions than the technological fixes being pushed by the transportation industry. This is because every journey we make burns some form of energy—usually some form of fossil fuel—and there is an inverse relationship between the carbon we burn in our machines and the food calories we burn when choosing how to get around.

†

‡

Even if you don’t care about your own health or the health of the environment, the relationship between urban design, health, and climate change planning touches your life and your bank balance. That’s because the dispersed city that nudges millions of people toward inactivity—and exposes them to air pollution and traffic crashes—simultaneously creates financial burdens for all of society. We know that obese people have more medical troubles. But they also miss work more frequently owing to illness and disability. They also work fewer years than healthy people. In the United States, this costs society a thundering $142 billion every year.

*

Meanwhile, pollution from auto-dominated roads causes tens of billions more in health-care costs. And then there are the costs incurred by traffic accidents, which run as much as $180 billion annually. Since the damage is directly related to the distance people drive every day, just reducing the frequency and length of automobile trips can ease the burden on emergency services, productivity, and the health-care system.

†

For years, none of these expenses were considered when transportation departments funded new roads and highways; they were the responsibility of other people working in other agency silos. But when you take the wide view, it becomes clear that Bogotá’s TransMilenio, New York’s bike lanes, and Vancouver’s laneway housing project are all exercises in long-term austerity. In fact, just about every measure I’ve connected to happy urbanism also influences a city’s environmental footprint and, just as urgent, its economic and fiscal health. If we understand and act upon this connectedness, we just may steer hundreds of cities off the course of crisis.

There Is No Such Thing as an Externality

Even before widespread acknowledgment of human-caused climate change, Jane Jacobs warned that the city is a fantastically complex organism that can be thrown into an unhealthy imbalance by attempts to simplify it in form or function. In

Cities and the Wealth of Nations

she warned specifically about the tendency for designers and planners to overscale: the larger an organism or economy, the more unstable it would become in changing times, and the less the likelihood that the system would be able to self-correct. Most city builders paid no attention. They pursued greater integration with global systems, relied more heavily on national and multinational industries and retailers to fuel their economies, and altered their cities’ very bone structure to accommodate extreme dispersal. The dispersalists saw order and efficiency in their segregated systems, but in many cases they were merely transferring energy costs from industry to regular citizens and governments.

Americans are learning the hard way that everything is connected to everything else. The modern urban landscape, whose construction fueled both the economic boom and a storm of carbon emissions and other pollution, is also responsible for many of the costs now crippling families and local governments alike, thanks to the indivisible relationship between land use, energy, carbon, and the cost of just about everything.

Consider the geography of the foreclosure crisis. As we’ve seen, the communities that fell hardest during the subprime implosion, places like exurban San Joaquin County, were classic low-density, segregated-use zones of single detached homes on plenty of acreage. This is because classic sprawl depends on cheap energy, and lots of it, to function. That dependence means that these neighborhoods are also climate killers because huge energy costs for households translate to huge greenhouse gas emissions. The relationship is clear: as emissions go up, operational affordability goes down.

*

Exurban homeowners have felt this pain for half a decade. But now city governments are being forced to reckon with this long-unaccounted relationship between distance and energy. Not only does sprawl development cost taxpayers more to build, it costs more to maintain, because each home in a typical community of dispersed single-family homes on big lots needs so much more paved street, drainage, water, sewage, and other services than a home in a denser, more walkable place. A neighborhood of detached homes and duplexes on small lots can be serviced for about a quarter of the cost of servicing typical large-lot detached homes. Dispersed communities also need more fire and ambulance stations than dense neighborhoods do. They need more school buses. The waste is astounding: in the 2005–06 school year, more than 25 million American children were bused to their public schools. The country spent $18.9 billion getting them there—that’s $750 for each bus-riding student, which could have been spent on actual learning.

Across the United States, broke city governments have found themselves unable to fund police, fire, and ambulance services, let alone school buses or the maintenance of roads, parks, and community centers. Cities stretched so far, so fast, for so long, at such low densities that the country now faces a massive unfunded liability for infrastructure maintenance. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has warned that repairing the country’s major infrastructure will cost more than $2 trillion.

Save the Planet and Your Bank Account

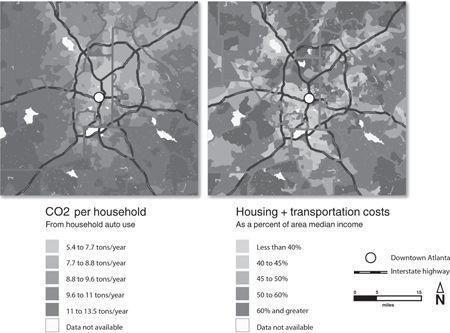

Residents of denser, more connected neighborhoods in central Atlanta are not only saving money by paying less in combined housing and transportation costs (

right

). They are also fighting climate change by producing less greenhouse gas emissions (

left

) than residents in Atlanta’s sprawling suburbs. In both cases, the savings are a result of system design.

(Scott Keck/Cole Robertson and Center for Neighborhood Technology: Housing and Transportation Index)

Many North American cities are just waking up to the fact that they have been engaging in a massive urban Ponzi scheme, with new development creating short-term benefits in development fees and tax revenues but even bigger long-term costs that pile up faster than cities’ ability to pay them off. In the boom years, cities kicked the great reckoning down the road. But now the maintenance costs are coming due, the development fee revenues from the boom years have dried up, and giant potholes are appearing in civic budgets. Building more of the same will not help cities get back on track or on budget. Cities have got to find ways to draw strength rather than weakness from the essential interconnectedness of land use, energy systems, and their own budgets. This means policy makers—and voters—need to start saying no to what once seemed like obvious paths to prosperity.

Jobs, Money, and Geometry

Most of us agree that development that provides employment and tax revenue is good for cities. Some even argue that the need for jobs outweighs aesthetic, lifestyle, or climate concerns—in fact, this argument comes up any time Walmart proposes a new megastore near a small town. But a clear-eyed look at the spatial economics of land, jobs, and tax regimes should cause anyone to reject the anything-and-anywhere-goes development model. To explain, let me offer the story of an obsessive number cruncher who found his own urban laboratory quite by chance.

Joseph Minicozzi, a young architect raised in upstate New York, was on a cross-country motorcycle ride in 2001 when he got sidetracked in the Appalachian Mountains. He met a beautiful woman in a North Carolina roadside bar and was smitten by both that woman and the languid beauty of the Blue Ridge region. Now they share a bungalow with two dogs in the mountain town of Asheville.

Asheville is, in many ways, a typical midsize American city, which is to say that its downtown was virtually abandoned in the second half of the twentieth century. Dozens of elegant old structures were boarded up or encased in aluminum siding as highways and liberal development policies sucked people and commercial life into dispersal. The process continued until 1991, when Julian Price, the heir to a family insurance and broadcasting fortune, decided to pour everything he had into nursing that old downtown back to life. His company, Public Interest Projects, bought and renovated old buildings, leased street-front space out to small businesses, and rented or sold the lofts above to a new wave of residential pioneers. They coached, coddled, and sometimes bankrolled entrepreneurs who began to enliven the streets. First came a vegetarian restaurant, then a bookstore, a furniture store, and the now-legendary nightclub, the Orange Peel.

When Price died in 2001, the downtown was starting to show signs of life, but his successor, Pat Whelan, and his new recruit, Minicozzi, still had to battle the civic skeptics. Some city officials saw such little value in downtown land that they planned to plunk down a prison right in the middle of a terrain that was perfect for mixed-use redevelopment. The developers realized that if they wanted the city officials to support their vision, they needed to educate them—and that meant offering them hard numbers on the tax and job benefits of revitalizing downtown. The numbers they produced sparked a eureka moment among the city’s accountants because they insisted on taking a spatial systems approach, similar to the way farmers look at land they want to put into production. The question was simple: What is the production yield for every acre of land? On a farm, the answer might be in pounds of tomatoes. In the city, it’s about tax revenues and jobs.

To explain, Minicozzi offered me his classic urban accounting smackdown, using two competing properties: On the one side is a downtown building his firm rescued—a six-story steel-framed 1923 classic once owned by JCPenney and converted into shops, offices, and condos. On the other side is a Walmart on the edge of town. The old Penney’s building sits on less than a quarter of an acre, while the Walmart and its parking lots occupy thirty-four acres. Adding up the property and sales tax paid on each piece of land, Minicozzi found that the Walmart contributed only $50,800 to the city in retail and property taxes for each acre it used, but the JCPenney building contributed a whopping $330,000 per acre

in property tax alone

. In other words, the city got more than seven times the return for every acre on downtown investments than it did when it broke new ground out on the city limits.

When Minicozzi looked at job density, the difference was even more vivid: the small businesses that occupied the old Penney’s building employed fourteen people, which doesn’t seem like many until you realize that this is actually seventy-four jobs per acre, compared with the fewer than six jobs per acre created on a sprawling Walmart site. (This is particularly dire given that on top of reducing jobs density in its host cities, Walmart depresses average wages as well.)

Minicozzi has since found the same spatial conditions in cities all over the United States. Even low-rise, mixed-use buildings of two or three stories—the kind you see on an old-style, small-town main street—bring in ten times the revenue per acre as that of an average big-box development. What’s stunning is that, thanks to the relationship between energy and distance, large-footprint sprawl development patterns can actually cost cities more to service than they give back in taxes. The result? Growth that produces deficits that simply cannot be overcome with new growth revenue.

*

“Cities and counties have essentially been taking tax revenues from downtowns and using them to subsidize development and services in sprawl,” Minicozzi told me. “This is like a farmer going out and dumping all his fertilizer on the weeds rather than on the tomatoes.”

*

Price, Whelan, and Minicozzi helped convince the city of Asheville to fertilize that rich downtown soil. The city changed its zoning policies, allowing flexible uses for downtown buildings. It invested in livelier streetscapes and public events. It stopped forcing developers to build parking garages, which brought down the cost of both housing and business. It built its own user-pay garages, so the cost of parking was borne by the people who used it rather than by everyone else. All of this helped make it worthwhile for developers to risk their investment on restoring old buildings, producing new jobs and tax density for the city.