Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (25 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

It can be tempting to see public conviviality as some kind of high science, dependent entirely on master planners and site programmers. But sometimes it is simply a matter of setting street life free around the city’s natural systems. For example, I once lived in Copilco, a messy collage of brick and rebar at the south end of Mexico City. My favorite place in this neighborhood was also its ugliest: a small plaza clinging to the edge of Eje Diez Sur, an eight-lane avenue where boxy minibuses known as

peseros

spewed blue smoke and lurched like bulls along the curb. Power transmission lines sagged overhead. Billboards advertising deodorant and mobile phones incised the skyline. For all this dreariness, something special happened on that plaza. The alchemy was twofold: First, a marble staircase at its west edge led down to a subterranean metro station. Every hour, hundreds of people flowed in and out, making connections with the

peseros

on Eje Diez or walking to the nearby National Autonomous University. Second, the plaza’s edges were lined with food stalls that intercepted the human flow. Vendors offered fresh-squeezed papaya and orange juice or the unofficial civic dish,

tacos al pastor

, from their corrugated steel shacks. At sunset the ugly skyline disappeared above lines of strung bulbs. Cumbia thunk-thunked through the night air. We travelers would gather in tight circles, plastic plates in hand, squeezing lime onto our tacos in the red-orange light of the

pastor

grill. The rough edge of Eje Diez became a living room, a nexus of conviviality on our journeys.

There is a message for all city makers here. It is that with the right triangulation, even the ugliest of places can be infused with the warmth that turns strangers into familiars by giving us enough reason to slow down. In this case, the subway station provided fuel for the fire of conviviality, but the flame depended on something actually happening in that space.

Something happened because something was allowed to happen,

a rare condition in cities dominated by automobiles or overregulation. But the food cart is starting to become a favorite of urban planners in rich cities. From Portland and Boston to Calgary, planners use mobile vendors as a means of tactical urbanism, infusing enough life to long-dead blocks to draw people and, eventually, brick-and-mortar businesses.

Velocities

For all its rough glory, there is a starker lesson rubbing up against that Copilco plaza. Getting there from the north requires a death-defying sprint through a stampede of

peseros

and even faster-moving taxis and private cars on Eje Diez, one of a network of highway-like arteries laid down across Mexico City in the 1970s. The road edge is hostile. The noise from engines and horns is unnerving. Venture beyond the parked

peseros

, and the danger feels totally enveloping. It changes your mood and your method, hardening you even as you approach it.

Cities that care about livability have got to start paying attention to the psychological effect that traffic has on the experience of public space.

Human bones have evolved to withstand impact with hard surfaces up to a speed of about twenty miles per hour, which is faster than a reasonably fit person can run.

*

So it is natural to get anxious when confronted with hard objects moving faster than that. Add a bunch of fast-moving objects to a space and make those objects big enough to pose a salient danger, and we get even more uncomfortable. Make those objects unpredictable and noisy, and you have created a perfect storm of stimulus to preoccupy anyone who might enter that space without the benefit of his own protective shell. Yet this is the condition we have designed into most modern city streets.

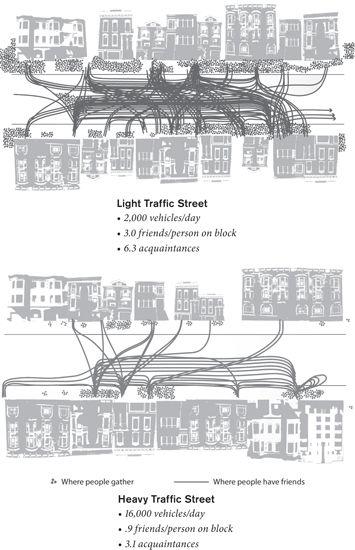

No amount of triangulation can account for the corrupting influence that high-velocity transport has on the psychology of public space. In a classic 1971 study of several parallel streets in San Francisco, Donald Appleyard found a direct relationship between traffic and social life. On a street with only light traffic (two thousand cars per day), children played on the sidewalks and street, people socialized on their front steps, and everyone reported having a tight web of contacts with neighbors on both sides of the street. On a nearly identical street with eight thousand cars passing per day, there was a dramatic drop in social activity and friendships. Another similar street with sixteen thousand passing cars saw almost nothing happening in the public realm, and social ties were few and far between. The only significant difference between these streets was the amount of car traffic pouring through them. But when asked to describe their neighborhood, people on the high-traffic street actually had a harder time remembering what the street edges looked like. In contrast to low-traffic street residents, they described their street as a lonely place to live. Automobiles had the power to turn a neighborhood street into a non-place.

This is partly a result of the danger and uncertainty that auto traffic infuses into a streetscape. But traffic’s social corrosion also stems from the noise it produces. We are less likely to talk to one another when it is noisy. We end conversations sooner. We are more likely to disagree, to become agitated, and to fight with the people we are talking to. We are much less likely to help strangers.

*

We become less patient, less generous, less helpful, and less social, no matter how detailed and inviting the street edge might be.

We are influenced by noise even when we don’t know it. Even the sound of light car traffic at night is enough to flood your system with stress hormones. Most city dwellers are conditioned to hear car horns and emergency vehicle sirens as signs of danger, even if we know that these sounds are intended for other people’s ears. And when we are stressed, we retreat from each other and the world.

How Traffic Alters the Social Life of Streets

In his famous 1972 study, Donald Appleyard showed how traffic influenced patterns of friendship on parallel streets in San Francisco. The more traffic there was, the fewer local friends and acquaintances residents had.

(All images based on Appleyard, Donald, and M. Lintell, “The Environmental Quality of Streets: The Residents’ Viewpoint,”

Journal of the American Planning Association

, 1972: 84–101; redesign by Robin Smith / Streetfilms)

This is perhaps the most insidious way that the system of dispersal has punished those who live closer together. Most of the noise, air pollution, danger, and perceived crowding in modern cities occurs because we have configured urban spaces to facilitate high-speed travel in private automobiles. We have traded conviviality for the convenience of those who wish to experience streets as briefly as possible. This is deeply unfair to people who live in central cities, for whom streets function as the soft social space between their destinations.

You cannot separate the social life of urban spaces from the velocity of the activities happening there. Public life begins when we slow down. This is why reducing velocity has become municipal policy in cities across the United Kingdom and in Copenhagen, where speed limits have been reduced to nine miles per hour on some streets. The city’s traffic director, Niels Torslov, told me that his department considers it a rounding success when most of the people they count on any particular street are not moving at all. It’s a sign that they’ve created a place worth being in.

The Social Life of Parking

Even the way we organize car parking can have a social effect. Transportation planner and Brookings Institution fellow Lawrence Frank found that people in cities are actually less likely to know their neighbors if the shops in their area have parking lots in front of them. The dynamic at play is obvious: those parking lots shift the balance of shoppers from local people toward people just passing through. You can’t blame a business for wanting to extend its reach. But when an entire city is designed around easy parking, then everyone shops farther from home, and the chances of bumping into people you might actually see again dwindles.

Ample, easy parking is the hallmark of the dispersed city. It is also a killer of street life. A cruise through Los Angeles illustrates the dynamic. The city’s downtown has been said to contain more parking spaces per acre than any other place on earth, and its streets are some of the most desolate. Back in the late 1990s, civic boosters hoped that the Disney Concert Hall, a stainless steel–clad icon by starchitect Frank Gehry, would pump some life into L.A.’s Bunker Hill district. The city raised $110 million in bonds to build space for more than two thousand cars—six levels of parking right beneath the hall. Aside from creating a huge burden for the building’s tenant, the Los Angeles Philharmonic (which is contractually bound to put on an astounding 128 concerts each winter season in order to pay the debt service on the garage), the structure has utterly failed to revive area streets. This is because people who drive to the Disney Hall never actually leave the building, noted Donald Shoup, a professor of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the world’s foremost expert on the effects of parking.

“The full experience of an iconic Los Angeles building begins and ends in its parking garage, not in the city itself,” Shoup and his graduate student Michael Manville wrote in a damning analysis. The typical concertgoer now parks underground, rides a series of cascading escalators up into the Disney Hall foyer, and leaves the same way. The result? The surrounding streets remain empty, largely bereft of cafés, bars, and shops, as well as the people who might stop in them. It’s a lonely place.

As much as we all love the convenience of proximal parking, the garage effect kills life on residential neighborhood streets, too. If all the people in your neighborhood have room for their cars inside their homes or under their apartments, you are much less likely to see them on the sidewalk. You realize how much this matters only when you see a fully realized alternative. I found one in the heart of Germany’s Black Forest.

Vauban, an experimental green neighborhood of about five thousand people, is built on a former military base, a 10-minute streetcar ride from the medieval heart of Freiburg. A checkerboard of apartments, town houses, and small parks are arranged amid a grid of roads and pathways, all gathered along a central avenue flanked by broad lawns, pathways, and a streetcar track.

At the crack of dawn on a September morning I joined a five-year-old boy named Leonard and his mother on his first bike ride to school. We wobbled along a quiet street to the main drag, where rush hour was in full swing—rush hour consisting almost entirely of people walking to school, to streetcar stops, and to two futuristic-looking garages on the edge of the village. The place was bubbling with just the kind of life that architects like to drop into their renderings.

That scene was the product of a velocity intervention. You can drive through most of Vauban if you want, but it is much faster and significantly less annoying to walk: on residential streets, the speed limit for cars is a languid five miles per hour. But the city’s real innovation is in the way it alters the geography of parking. Long-term on-street parking is forbidden. Meanwhile, Vauban’s residential ownership structure turns the economics of residential parking upside down. In most cities, the cost of parking is rolled into the sale price of your home. But if you move to Vauban, you have two options. If you own a car, you are contractually obligated to purchase a parking spot in one of the two garages at the edge of town. (That can be a shock. Leonard’s parents bought their parking spot for 20,000 euros.) But if you don’t own a car—and you are willing to sign an intimidating “car-free” pledge—you do not have to fork out for a parking spot. Instead, you buy a share of a leafy lot on the edge of town for about 3,700 euros. (This is an investment: if the car-free culture prevails, you will share that park with everyone. If Vauban requires more parking, you stand to make a sizable return.)

This rationalization of car costs means that no matter how Vaubanites get to work, they tend to walk or cycle when they are close to home. That’s why the streets are full of people. That’s why they are safe for five-year-old commuters.

What Vauban proves is that life can be infused into a community just by adjusting the speed of streets, and the distance between parking facilities and people’s front doors. The farther away the parking, the livelier the street. It may seem outrageous to parking-obsessed North Americans, but Vauban’s parking burden has helped make it one of the most popular suburbs of Freiburg. Leonard sure liked it. When we arrived at his school, the five-year-old turned to me and bellowed something in German. He beamed as his mother, Petra Marqua, translated, “Tomorrow I get to ride to school all by myself.”

Those slow streets, filled with so many familiar faces, made the ride so safe that Petra acquiesced.

When Roads Stop Being Roads

Most cities do not have the luxury of planning from scratch. The prime real estate in the densest parts of town has all been accounted for, so cities that want more space for people are left to trade airspace with developers in exchange for bonus plazas, or to invest heavily in acquiring new land. But these are not the only options, especially given the tremendous resource that we, as citizens, already control. All the real estate now used to facilitate the movement and storage of private automobiles is public, and it can be used any way we decide. Cities that are serious about the happiness of their citizens have already begun to confront their relationship with velocity. They are making what once seemed to be radical decisions about what—and whom—streets are for.