Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man (2 page)

Read Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man Online

Authors: Mark Changizi

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Chapter 1

Nature-Harnessing

Deep Secrets

I

t isn’t nice to tell secrets in front of others. I recently had to teach this rule to my six-year-old daughter, who, in the presence of other people, would demand that I bend down and hear a whispered message. To my surprise, she was genuinely perplexed about why communicating a message only to me, in the presence of others, could possibly be a bad thing.

Upon thinking about it, I began wondering: What exactly

is

so bad about telling secrets? There are circumstances in which telling secrets would appear to be the appropriate thing to do. For example, if Dick and Jane are over for a formal dinner at my house, and in order to spare my wife some embarrassment I lean over and whisper, “Honey, there’s chocolate on your forehead,” is that wrong? Wouldn’t it be worse to say nothing, or to say it out loud (or in a published book)?

The problem with telling secrets is not that there aren’t things worth telling others discreetly. Rather, the problem is that when we see someone telling a secret, it taps into a little program in our head that goes, “That must be very important information—possibly about

me

. Why else keep it from me?” The problem with secrets is that we’re all a bit paranoid, and afflicted with a bad case of “me, me, me!” The result is that secrets get imbued with weighty importance, when they mostly concern such sundries as foreheads and sweets.

Not only do we tend to go cuckoo over the covert, attributing importance to unimportant secrets, but we also have the predisposition to see secrets where there are none at all. Our propensity to see nonexistent secrets has engendered some of the most enduring human preoccupations: mysticism and the occult. For example, astrology, palm reading, and numerology are “founded” upon supposed secret meanings encoded in the patterns found in stars, handprints, and numbers, respectively. Practitioners of mysticism believe themselves to be the deepest people on Earth, dedicated to the ancient secrets of the universe: God, life, death, happiness, soul, character, and so on. Astrological horoscopes don’t predict the morning commute, and palm readers never say with eerie omniscience, “Don’t eat the yogurt in your fridge. It’s moldy!” The secrets are not only deep, but often personal: they’re about ourselves and our role in the universe, playing on our need for more “me, me, me.”

Even those who pride themselves on not believing in mystical gobbledygook often still enjoy a good dose of deep ancient secrets in fiction, which is why Dan Brown’s

The Da Vinci Code

did so well. In that novel secret codes revealed secret codes about other secret codes, and they all held a meaning so deep that people were willing to slay and self-flay for it.

Secrets excite us. But stars, palms, and numbers hide no deep, ancient secrets. (Or at any rate, not the sort mystics are searching for.) And stories like the

The

Da Vinci Code

are, well, just stories. What a shame our real world can’t be as romantic as Dan Brown’s fictional one, or the equally fictional one mystics believe they live in. Bummer.

But what if there

are

deep and ancient secrets? Real ones, not gobbledygook? And what if these secrets

are

about you and your place in the universe? What if mystics and fiction readers have been looking for deep secrets in all the wrong places?

That’s where this book enters the story. Have

I

got some deep secrets for you! And as you will see, these ancient secrets are much closer than you may have thought; they’re hiding in plain sight. In fact, as I write these very words I am making use of three of the deepest, ancientest secret codes there are. What are these secrets? Let me give you a hint. They concern the three activities I’m engaged in right now: I am

reading

(my own writing),

listening to speech

(an episode of bad TV to keep me awake at 2 a.m.), and

listening to music

(the melodramatic score of the TV show). My ability to do these three things relies on a code so secret few have even realized there’s a code at all.

“Code, schmode!” you might respond. “How lame is that, Changizi? You tantalize me with

deep

secrets, and yet all you give me are run-of-the-mill writing, speech, and music! Where are the ancient scrolls, Holy Grails, secret passwords, and forgotten alchemy recipes?”

Ah, but . . . I respond. The secrets underlying writing, speech, and music

are

immensely deep ones.

These secret codes are so powerful they can turn apes into humans.

As a matter of fact, they

did

turn apes into humans.

That’s deeper than anything any mystic ever told you!

And it is also almost certainly truer. So shove that newspaper horoscope and that Dan Brown novel off your coffee table, and make room for this nonfiction story about the deepest ancient secret codes we know of . . . the ones that created us.

To help get us started, in the following section I will give you a hint about the nature of these codes. As we will see, the secret behind the codes is . . .

nature itself

.

Mother Nature’s Code

If one of our last nonspeaking ancestors were found frozen in a glacier and revived, we imagine that he would find our world jarringly alien. His brain was built for nature, not for the freak-of-nature modern landscape we humans inhabit. The concrete, the cars, the clothes, the constant jabbering—it’s enough to make a hominid jump into the nearest freezer and hope to be reawakened after the apocalypse.

But would modernity really seem so frightening to our guest? Although cities and savannas would appear to have little in common, might there actually be deep similarities? Could civilization have retained vestiges of nature, easing our ancestor’s transition? And if so, why

should

it—why would civilization care about being a hospitable host to the freshly thawed really-really-great-uncle?

The answer is that, although we were born into civilization rather than melted into it, from an evolutionary point of view we’re an uncivilized beast dropped into cultured society. We prefer nature as much as the next hominid, in the sense that our brains work best when their computationally sophisticated mechanisms can be applied as evolution intended. Living in modern civilization is

not

what our bodies and brains were selected to be good at.

Perhaps, then, civilization shaped itself for

us

, not for thawed-out time travelers. Perhaps civilization possesses signature features of nature in order to squeeze every drop of evolution’s genius out of our brains for use in the modern world. Perhaps we’re hospitable to our ancestor because we have been hospitable to

ourselves

.

Does

civilization mimic nature? I believe so. And I won’t merely suggest that civilization mimics nature by, for example, planting trees along the boulevards. Rather, I will make the case that some of the most fundamental pillars of humanity are thoroughly infused with signs of the ancestral world . . . and that, without this infusion of nature, the pillars would crumble, leaving us as very smart hominids (or “apes,” as I say at times), but something considerably less than the humans we take ourselves to be today.

In particular, those fundamental pillars of humankind are (spoken) language and music. Language is at the heart of what makes us apes so special, and music is one of the principal examples of our uniquely human artistic side.

As you will see, the fact that speech and music

sound like other aspects of the natural world

is crucial to the story about how we apes got language and music. Speech and music culturally evolved over time to be simulacra of nature. Now

that’s

a deep, ancient secret, one that has remained hidden despite language and music being right in front of our eyes and ears, and being obsessively studied by generations of scientists. And like any great secret code, it has great power—it is so powerful it turned clever apes into Earth-conquering humans. By mimicking nature, language and music could be effortlessly absorbed by our ancient brains, which did

not

evolve to process language and music. In this way, culture figured out how to trick nonlinguistic, nonmusical ape brains into becoming master communicators and music connoisseurs.

One consequence of this secret is that the brain of the long-lost, illiterate, and unmusical ancestor we unthaw is no different in its fundamental design from yours or mine. Our thawed ancestor might do just fine here, because our language and music would harness

his

brain as well. Rather than jumping into a freezer, our long-lost relative might instead choose to enter engineering school and invent the next-generation refrigerator.

The origins of language and music may be attributable, not to brains having evolved language and music instincts, but rather to language and music having culturally evolved

brain instincts

. Language and music shaped themselves over many thousands of years to be tailored to our brains, and because our brains were cut for nature, language and music mimicked nature . . . and transformed ape to man.

Under the Radar

If language and music mimic nature, why isn’t this obvious to everyone? Why should this have remained a secret? It’s not as if we have no idea what nature is like. We’re not living on the International Space Station, and even those who are on the Space Station weren’t

raised

up there! We know what nature looks and sounds like, having seen and heard countless examples of it. So, given our abundant experiences of nature, why haven’t we noticed the signature of nature written (I propose) all over language and music?

The answer is that, ironically, our experiences with nature don’t help us consciously comprehend what nature

in fact

looks and sounds like. What we are aware of is already an assembled

interpretation

of the actual data our senses and brains process. This is true of you whether you are a couch potato extraordinaire or a grizzled expedition guide just returned from Madagascar and leaving in the morning for Tasmania.

For example, I am currently in a coffee shop—a setting you’ll hear about again and again—and when I look up from the piece of paper I’m writing on, I see people, tables, mugs, and chairs. That is, I am consciously aware of seeing these

objects

. But my brain sees much more than just the objects. My early visual system (involved in the first array of visual computations performed on the visual input from the retina) sees the individual contours, and does

not

see the combinations of contours. My

intermediate-level

visual areas see simple combinations of several contours—for instance, object corners such as “L” or “Y” junctions—but don’t see the contours, and don’t see the objects. It is my

highest-level

visual areas that see the objects themselves, and I am conscious of my perception of these objects. My conscious self is, however, rarely aware of the lower hierarchical levels of visual structure.

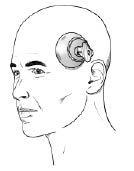

For example, do you recall the figure at the start of the chapter—the person’s head with a lock and key on it? Notice that you recall it in terms referring to the

objects

—in fact, I just referred to the image using the terms

person, head, lock

, and

key

. If, instead, I were to ask you if you recall seeing the figure that had a half dozen “T” junctions and several “L” junctions, you would likely not know what I was talking about. And if I were to ask you if you recall the figure that had about 40 contours, and I then went on and described the geometry of each contour individually, you would likely avoid me at cocktail parties.

Not only do you (your conscious self) not see the lower-level visual structures in the image, you probably won’t find it easy to talk or think about them. Unless you have studied computational vision (i.e., studied how to build machines that see) or are a vision scientist, you probably haven’t thought about how contours intersect one another in images. “Not only did I not see T or L junctions in the image,” you might respond, “I don’t even know what you’re talking about!” We also have great trouble talking about the orientation and shapes of contours in our view of three-dimensional scenes (something that came to the fore in the theory of illusions I discussed in

The Vision Revolution

).

Thus, we may

think

we know what a chair looks like, but in a more extended sense, we have little idea, especially about all those lower-level features. And although parts of our brain

do

know what a chair looks like at these lower levels, they’re not given a mouthpiece into our conscious internal speech stream. It is our inability to truly grasp what the lower-level visual features are in images that explains why most of us are hopeless at drawing what we see. Most of us must undergo training to become better at accessing the lower levels, and even some of the great master painters (such as Jan Van Eyck) may have projected images onto their canvases and

traced

the lower-level structures.

Not only do we not truly know what nature looks like, we also don’t know what it

sounds

like. When we hear sounds, we hear the meaningful events, not the lower-level auditory constituents out of which they are built. I just heard someone at the next table cutting something with her fork on a ceramic plate. I did not consciously hear the low-level acoustic structure underlying the sound, but my lower-level auditory areas

did

hear just that.

For both vision and audition, then, we have a hierarchy of distinct neural regions, each a homunculus (“little man”) great at processing nature at

its

level of detail. If you could go out for drinks with these homunculi, they’d tell you all about what nature is like at lower and middle hierarchical scales. But they’re not much for conversation, and so you are left in the dark, having good conscious access only to the final, highest parts of the hierarchy. You see objects and hear events, but you do not see or hear the constituents out of which they are built.

You may now be starting to see how language and music could mimic nature, yet we could be unaware of it. In particular: what if language and music mimic all the lower- and middle-level structures of nature, and only fail to mimic nature at the highest levels? All our servant homunculi would be happily and efficiently processing stimuli that appear to them to be part of nature. And yet, because the stimuli may have a structure that is not “natural” at the highest hierarchical level, our conscious self will only see the dissimilarity between our cultural artifacts and nature.