Here Comes the Night (45 page)

Losing Web IV and Bang Records to Berns left Wexler embittered. It wasn’t the money—it was the money. One final matter remained. Berns signed over the small piece they gave him of their Cotillion Music. Atlantic needed to consolidate ownership of their music publishing to package all the company’s assets for sale. Berns signed off for a reasonable consideration, $70,000, but Wexler couldn’t bring himself to pay, much as he had refused to give Leiber and Stoller the money their audit showed due.

In the giddy excitement of acquiring half of his publishing, the Atlantic partners had given Berns the small interest in their publishing, an act of generosity Wexler now felt that paying off would be unjustified punishment. Berns, who tapped himself out paying off Atlantic, needed the money. Wexler dodged Berns’s persistent demands for payment, but he had no long-term strategy for dealing with Berns beyond not returning his calls. Wexler reached out to Morris Levy to see if Levy could bring some pressure to bear on Berns. He decided to muscle Berns, so Morris made a couple of calls.

Berns, meanwhile, had unloaded his problems on Tommy Eboli, who also made a couple of calls. Ilene made a secret, desperate call of her own to Jerry Wexler at his Great Neck place to urge him to stop. “You don’t know what the hell you’re dealing with,” she told him. When Wexler rebuffed her, she asked Berns to call off Eboli, and Berns agreed everything had gone too far. He talked to Tommy. Too late, Eboli told Berns. Levy started something that needed to be finished. “It’s out of my hands,” he said. “You don’t realize who I am.”

A meeting was arranged at the Roulette offices. Wassel was so worked up about the meeting, Patsy Pagano made him wait at a nearby coffee shop. Miltie Ross came along. Big Miltie ran hookers up and down Broadway, made a bundle counterfeiting subway tokens, and kept his hand in the music business since the big bands. He did a lot

of business with Ertegun and Wexler out of his Award Music office in the Brill Building. He ran their budget-line LP label, Clarion Records, which repackaged old Atlantic stock for bargain basement retail, a gray area of the business where wiseguys like Big Miltie liked to operate.

Levy invited his partner Dominick Ciaffone and a couple of their other gangland associates, highly ranked soldiers, but when Patsy Pagano showed up with Genovese boss Tommy Eboli, Levy’s hand was trumped. Gangsters picked up Ahmet Ertegun walking down the sidewalk and brought him to the meeting. Whatever series of events Wexler set in motion when he first called Levy played out on an entirely different level than he originally intended. These guys carved up the deal and cut themselves a slice.

When it was done, Patsy Pagano and Big Miltie went to see Wexler at his office. Wexler was terrified just to be sitting across his desk from Pagano. They made jokes about breaking his daughter’s legs. Wexler didn’t laugh. They told Wexler that not only would he have to pay Berns the cash, but also as part of the settlement, he would have to turn over the recording studio the company just bought. Both parts of the settlement needed to be kept off the books, out of sight of the due diligence of any potential buyer of Atlantic Records.

The studio, Talentmasters, was a dump on the fourth floor above Tad’s Steaks on Forty-Second Street off Times Square, an old fur storage locker where you could hear the rats in the elevator shaft and the shag carpet smelled of cat piss. Atlantic had only recently completed purchasing the operation. Atlantic’s own studio had become so busy, the label had been booking overflow into Talentmasters, sending over a steady stream of Atlantic acts such as the Rascals, Ben E. King, Mary Wells, and others. Basically, Tommy Eboli wanted to get into the studio business with Berns, who took him to see Atlantic counsel Paul Marshall when arranging some of the details on the transfer of ownership. Wexler, scared for his life, hired bodyguards. He never forgave Berns.

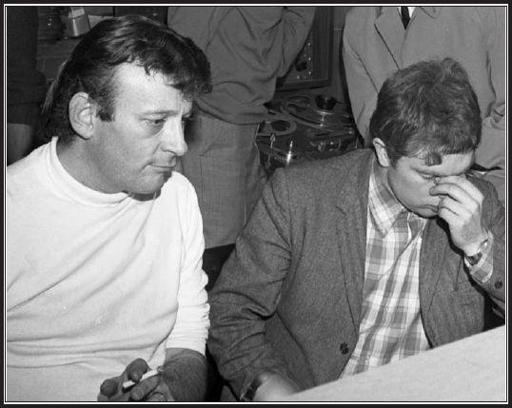

Bert Berns, Van Morrison at “Brown Eyed Girl” session.

F

REDDIE SCOTT WAS

doing a show in Philadelphia when his twin sister died unexpectedly of a heart attack. He came home the next day for the funeral, where Wassel found him and dragged him away from his grieving family through the snowy streets to the recording studio. His debut single for the Shout label, “Are You Lonely for Me Baby,” was streaking up the charts, headed for number one r&b. Berns needed Scott to finish an album and he had just the song for Scott’s next single, his Solomon Burke breakthrough, “Cry to Me.” This time, he slowed down the track even more than he did with Betty Harris, painfully, excruciatingly slow. Tears rolled down Scott’s face as he spit out every mouthful. Scott wasn’t the only one crying. Everybody in the studio was crying.

Wassel came by the Bang Records office daily, sometimes just sat on Berns’s couch for hours. Patsy Pagano stopped by occasionally. Pagano and Wassel dragged some poor son of a bitch they found downstairs bootlegging records up to the Bang office and threw him in a chair in front of Berns’s desk. Ed Chalpin made soundalike records. He rushed out cheap covers of the day’s hits and spread them around the world as fast as he could. Ironically, Berns used to play on some of his sessions when he was starting out.

They brought him into the office to admonish him. Berns turned away and looked out the window. While Berns wasn’t looking, Patsy Pagano hit the dumb bastard so hard, he broke his own hand. Berns swiveled around. “See, I warned you,” he said.

Wassel saw nothing wrong with taking vigilante action on bootleggers. He broke up a couple of operations—literally, with sledgehammers and pipes—in Brooklyn. He and his confederate threw steak to the guard dogs and climbed the fence. He liked to wear a large ring with his initials spelled out in diamonds that would leave cuts. He knew to swing down on people when you hit them in the face because they get frightened with blood in their eyes. Berns went along on one of their raids on some stupid sucker who had bootleg 45s stacked on broomsticks in his garage out on Ditmars Boulevard in Astoria, but he called off Wassel and his goons when he saw a baby sleeping in a crib in the garage. Wassel let the guy off with a stern admonition.

Pagano and his wife, Laura, showed up at the hospital in February when Berns’s daughter, Cassandra Yvette, was born. Al and Sylvia Levine, Berns’s sister and brother-in-law, were visiting. They didn’t get along all that comfortably with Bert and Ilene, but they were family. Patsy handed Berns an attaché case. He clicked it open and showed his brother-in-law. It was full of cash—the Atlantic Records settlement. Al knew the Atlantic guys had cheated Berns and that he had the money coming, but he’d never seen so much cash.

There’s something happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear

, went the line in “For What It’s Worth,” the hit single by the new Atlantic Records recording artists from Los Angeles, Buffalo Springfield. Ahmet Ertegun was anxious to get Atlantic more deeply involved in this new rock movement that already proved rewarding with the Young Rascals and Sonny & Cher. He dispatched his brother Nesuhi to Los Angeles to see the band perform. Through the same Hollywood sleazebags that managed Sonny & Cher, Ertegun was able to sign the group away from Jac Holzman of Elektra and Lou Adler of Dunhill for a king’s ransom

of $12,500, without the benefit of having heard one song demo. There was a lot of excitement and interest in the industry over what

Billboard

called “pop/hippie acts,” but there was also a vast amount of confusion and misunderstanding.

Canadian sociologist Marshall McLuhan called it “the hi-fi/stereo changeover.” As inexpensive home stereo players became more available, the market for pop music began to shift from little 45 RPM singles to the 33 ⅓; long-playing albums, big records with small holes. This transition changed the pop music world in deep and fundamental ways. The audience and the music were both growing up. A key passage took place in November 1965, when the Beatles, the industry’s leading act, released a new album,

Rubber Soul

, with no singles. A couple of weeks later, the band put out a new single not contained on the album, a double-sided instant smash, “Day Tripper” and “We Can Work It Out.” The stereo production on the album was, at times, clumsy and awkward, while the monaural hit single sounded like a bullet coming out of cardboard car radio speakers, but the Beatles as recording artists were drawing a clear distinction between the kind of work they would do on albums and singles.

On the West Coast, new long-haired rock groups with funny names were launching records on the charts every week. In San Francisco, a hundred thousand hippies gathered in Golden Gate Park to listen to rock groups that didn’t exist a year before. Peace and love, brother and sister. Jefferson Airplane loves you and the Peanut Butter Conspiracy is spreading. While old-time independents around New York were a vanishing breed, A&M Records in Los Angeles was installing new recording studios in the company’s million-dollar headquarters, Charlie Chaplin’s old studios on La Brea Avenue, after selling more than four and a half million copies of the long-playing album

Whipped Cream and Other Delights

by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, the

A

of A&M. Jac Holzman’s Elektra Records was building a modern new Hollywood office complex and rapidly expanding beyond the Greenwich Village

folk scene roots of the label into the pop charts with Los Angeles–based rock groups such as Love or the Doors.

Berns went to Los Angeles in March 1967, as soon as Ilene was well enough to travel after the new baby. For her, this was a triumphant return home and the first thing she did was have Bert take her to Dolores’ on Wilshire in the limousine for a hamburger on the way to the hotel. She made Berns tour Beverly Hills real estate—they checked out actor Laurence Harvey’s place—but he looked ill at ease and out of place, all pasty and paunchy, playing with baby Brett in the hotel swimming pool. They talked about moving to California, Berns getting into movie soundtracks, but he was such a New Yorker. She felt good being in California, back in shape after the baby, and enjoyed wearing a negligee to bed. Her husband took one look, offered his trademark “Ooh-la-la,” and, one uncomfortable, slightly painful

schtup

later, Ilene was pregnant again.

Berns was in California to make a series of albums with the noted astrologer Sydney Omarr, author of countless books about the stars and signs and syndicated

Los Angeles Times

columnist. Berns cut Omarr doing one album for each astrological sign; one side about the particular sign and the other side about how that sign related to each of the other signs. This was a long way from

Rubber Soul

, but Berns was thinking about the growing album market.

He sought out Van Morrison through Phil Solomon, unaware that Them had crashed and burned the previous summer of 1966 in Los Angeles. The band took a three-week residency at Hollywood’s Whisky a Go Go, where opening acts had included Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band, Buffalo Springfield, the Association, and the Doors, who finished their joint appearances with the two Morrisons—Van and Jim—sharing the stage singing “Gloria” and “In the Midnight Hour.” During the Whisky run, Them fired Phil Solomon long-distance over money. Solomon washed his hands of the whole lot. After three months in California, the band splintered and most made their way home.

When Berns reached Van Morrison in Belfast, Morrison had nothing going on. There were several versions of Them touring. He was living with his parents and spending long hours spinning songs by himself into a reel-to-reel tape recorder he bought in the States. He was bitter, angry, and frequently drunk. Berns thought he could be a rock and roll version of the Irish poet Brendan Behan. He signed Morrison to a record deal with Bang, sent him $2,500, and flew him over to make an album in March 1967.

At A&R Studios on West Forty-Eighth Street, twenty-two-year-old Van Morrison was surrounded by the cream of New York session musicians—keyboard players Artie Butler and Paul Griffin, guitarists Eric Gale, Hugh McCracken, and Al Gorgoni, and drummer Gary Chester. Cissy Houston and her ladies were there. Garry Sherman wrote out the charts almost as quickly as Morrison could play him the songs. Brooks Arthur was engineering and Jeff Barry was hanging around. Guitarist Gale grabbed the electric bass on “Brown-Eyed Girl,” an instrument Gale played with a flat pick, giving his downstrokes a rigid, hard-edged attack. Arranger Sherman had never seen anyone play the electric bass with a flat pick before.

Guitarist Gorgoni listened to Morrison run down the song on acoustic guitar and slowly put together the calypso-flavored introduction on his Gibson L-5 over the course of the first few run-throughs. By the time they cut the master on take twenty-two, Gorgoni had polished his sprightly, dancing guitar introduction into a solid, crafted piece. Berns, Barry, and Brooks Arthur joined the background chorus and Berns sang louder than anyone. Morrison originally called the song “Brown-Skinned Girl,” but Berns knew better.