Hetty Feather (19 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

She slammed the door shut on me, rattled the

key in the lock and marched off.

'Please come back, please, please!' I screamed,

though I knew she would not relent.

At last I drank the water down in three great gulps,

and ate the single slice of dry bread. It was almost

pitch dark now, and I hunched up on my blanket. I

could not think up a single new story, but old tales

from the

Police Gazette

started swirling in my mind.

Mad Flora crouched beside me, knife clutched at the

ready. The Meat-axe Murderer slavered at the door,

dripping with blood.

I pulled the blanket right over my head, but

they crept underneath too. I put my hands over

my ears because they were whispering menacingly,

threatening me.

'Oh, Hetty, are you in there?'

Wait! Was this a real voice, outside my attic

prison? I heard knocking at my door.

'Hetty? Have they locked you in there?'

I knew that husky voice.

'Is it really you, Ida?'

'Oh dear God, they've really locked you up

inside.'

'Ida, please, turn the key and let me out!'

'I can't, my love, those witches have taken

away the key,' she said. She sounded as if she was

crying herself.

'How long are they going to keep me here?' I

asked desperately.

'I don't know. I think maybe all night long. I'm

so very sorry, Hetty. I only just found out. I didn't

see you at dinner but I thought I'd simply missed

you. When I did not see you at supper either, I asked

Polly and she said they'd taken you away to punish

you. She was in tears too, poor girl, saying it was all

her fault, that you were trying to protect her from

Miss Morley. What did you

do

to her, Hetty?'

'I snatched her ruler away when she'd struck

Polly. Oh, how I wish I'd struck her with it. I hate

her. I hate them all.'

'I hate them too. You must try to be brave, dear

Hetty. They will have to let you out tomorrow. If

they don't, I will go to a governor's house and report

them for wicked cruelty,' Ida said wildly.

'I'm not sure I can manage a whole night,' I

wept. 'It's so dreadfully dark and I'm so scared all

by myself.'

I thought of little Gideon then, all by himself in

the squirrel house the night we went to the circus.

No wonder he'd been so traumatized. Was I going to

be shocked senseless too?

'You're not alone, Hetty,' said Ida. 'I will stay. I

cannot get in, but I am only the other side of your

door. I will wait until you go to sleep.'

'But you will get into trouble if they catch you.'

'They won't catch me. If I hear anyone coming,

I'll run along the corridor and hide, and then

creep back afterwards. I'm not leaving you here so

frightened.'

'You're so good to me, Ida.'

'I'd give anything to look after you properly,

Hetty. For two pins I'd slap those evil witches until

they gave me the key, and then I'd let you out and

have you sleep in my own bed – but I have to keep

my position. I'd never get any other work without a

good reference, and I'm not going to end up in the

workhouse. I'll tell you a secret, Hetty. I spent three

years there, and it was a dreadful, dreadful place.

No, I'm doing well for myself now and saving up my

wages. I've the future to think of.' She paused for a

long moment. 'Shall I tell you . . .?'

'Tell me what, Ida?'

'No, no, maybe not now, not yet.' She was silent.

'Are you still there, Ida?' I asked anxiously.

'Yes, of course I am. You curl up, my dear, and try

to go to sleep. Did they give you a mattress?'

'I've got a blanket, but it smells so horrid.'

'Put your cap over your nose – that will

smell of fresh laundering and hair oil, good smells.

Now, you're the girl for picturing. Picture you're

lying on a soft scented pillow, so fresh and dainty,

and you have a feather mattress and a beautiful

warm quilt. Oh, you are getting so cosy now, aren't

you, dear?'

'I didn't think

you

could picture, Ida!'

'I can do lots of things, Hetty. Now nestle under

your splendid quilt. Shut your eyes, dear. You're

getting very sleepy. You're going to go fast asleep

and have happy dreams,

such

happy dreams. One

day all your dreams will come true, Hetty. All my

dreams too . . .' Ida's voice murmured on and on,

and somehow the stout door splintered away and

we were together, both of us in our soft feather bed,

lying on fresh pillows . . .

Then I woke up with a start, my neck twisted, my

whole body aching, locked in the dark all alone. But

somehow it wasn't quite as bad as before because

Ida's voice echoed in my head, helping me picture

the bed, and after a long time I fell asleep again.

Then I heard the key in the lock. The door opened

and I was blinking in daylight.

'Well, well, well, Hetty Feather!' Matron Bottomly

peered in at me, a look of triumph on her ugly face.

'You look suitably chastened, child. Are you truly

sorry, or do you need another twenty-four hours to

teach you your lesson?'

'I am very sorry, Matron,' I said meekly, my head

bowed, because I could not stand the thought of

further imprisonment.

'I am glad to see you truly penitent at last,' said

Matron Bottomly, smiling grimly. 'I'm pleased that

vicious spirit of yours is broken at last. Now perhaps

you will show suitable respect to your elders and

betters.'

Oh, how I hated her, talking about me as if I was

a tamed wild beast. Of course I wasn't the slightest

bit sorry I'd stuck up for poor Polly. I had no respect

whatsoever for Matron Bottomly or Miss Morley.

They were undisputedly my elders but they certainly

weren't

my betters. They were cruel, wicked women,

not fit to look after children. How dare they beat us

and lock us up like criminals and act as if it was for

our benefit!

I resolved to run away.

'Oh, Hetty, I will run away too,' Polly said,

hugging me.

Her hands were still scored with red weals from

Miss Morley's ruler, and her eyes were red too,

because she'd cried bitterly the entire time I'd been

incarcerated.

We tried to concoct a sensible plan of action. We

fancied ourselves the cleverest girls but we lacked

inventive ideas. We knew so little of the world

outside the hospital. We only knew our foster homes

– and so we thought of our lost foster mothers.

'If Miss Morrison knew the way we are treated

here, I'm sure she'd take me back into her care.

She'd take you too, Hetty, because you are so bright

and clever.'

'If Mother knew they'd kept me locked up in an

attic all night, she'd

definitely

take me back – and

my goodness, Jem would rise up and seize Matron

Bottomly and kick her up her stinking bottom,'

I declared. 'And of course you could stay with

us,

Polly.

You might care for my brother Nat, who is almost

as dear as Jem, and then you can marry him when

we are older and we can live in adjoining cottages.'

We alternated futures, flying between one

household and another, the way we'd pictured

our pretend visits as little children. It had been so

easy when we were small girls, but now it seemed

incredibly difficult. We could fly there in an instant

in our imagination, but it was a far harder task

working out each step in reality. We had no clear

idea how to get to our foster homes. I knew we had

to go on a long journey by train, but I did not even

know the names of the stations – and though I had

a little money (Jem's sixpence and my Christmas

pennies), I knew they would not be nearly enough

to pay the fare.

'How will we actually get out of the hospital?'

said Polly.

We rarely set foot outside the grounds. We had

been taken to tea at a governor's house several

times, and once some girls had been picked to go

on an outing to Hampton Court – but not us. We

were always carefully guarded, and the grounds

were regularly patrolled by staff. Surely if we simply

started running, they would seize us and bring

us back? I could not stand the thought of further

incarceration in the attic room.

'We have to make firm plans,' I said, though I

did not have any idea how to do this. I'd lived in the

hospital so long that the outside world had faded

like a dream. I had pictured home often enough, but

I'd added so many details that now I wasn't sure

what was real.

The mother and father in my mind were now like

good guardian angels. Yet contrarywise I could also

remember Mother paddling me, Father shouting

angrily. My brothers and sisters seemed like siblings

in a storybook, not really connected to

me.

Martha

was now simply the girl in spectacles who sang

sweetly in the chapel on Sundays.

I even felt I'd lost contact with Gideon. I'd dared

my dressing-as-a-boy trick twice more in the infants

school, and last year at the boys' sports day I'd

looked hard for him. He eventually spotted me and

risked edging close to say hello. I did not recognize

him till he did so. He was so tall now, and had filled

out a little, seeming less sad and spindly.

'Hello, Hetty,' he said softly.

'Oh, Gideon, it's really you!' I said.

I did not care about hospital rules. I threw my

arms around him. However, it felt odd, as if I was

embracing a stranger. We asked each other politely

if we were all right, but then stood smiling shyly,

at a loss for further conversation. I was so glad he

was still talking properly, but I did not like to point

this out in case it embarrassed him. Eventually I

asked him if he ever thought of Mother and home.

I wished I'd held my tongue because his brown eyes

grew misty. He shook his head, though I was sure he

was lying. Then one of the boys' teachers looked our

way and Gideon ran off hastily.

I had glimpsed him since, going in and out of the

chapel, but was not even sure it was really him –

there were so many tall thin boys with brown eyes.

I decided I could not include him in my escape

plans. We had been parted too long. It was almost

as if he wasn't my brother any more. There was

only one brother I was sure of. My vision of Jem

shone like a lantern in my head. I was sure I still

knew every freckle on his dear face, every curl of

his hair, every curve of his ear. I knew the sound

of his sneeze, his yawn, his merry laughter. I felt

I could instantly pick him out from fifty thousand

other boys. He would be almost a man now, able to

find work. He could look after me – and Polly too.

She was dearer to me now than any of my sisters.

She did not give answers now in Miss Morley's

class. She wrote down her sums silently from the

board, and if Miss Morley made mistakes, she

copied them without comment – though she bit

her lip. Alone with me, she talked as usual, but she

was quiet with everyone else, her head bent as if to

escape notice.

But someone was quite definitely noticing her.

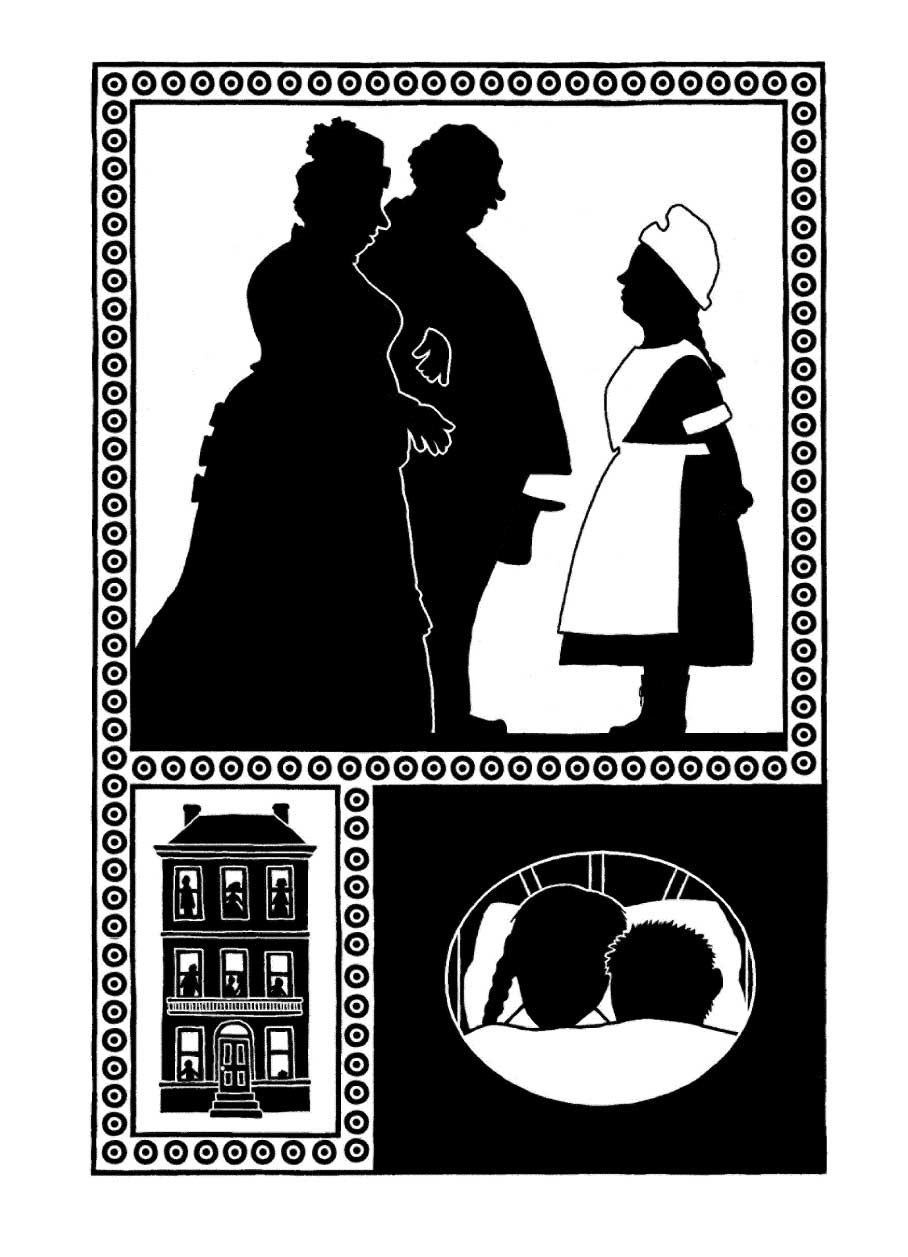

A large woman dressed all in black, with a very

pale face and dark shadows under her eyes, started

coming regularly on Sundays, leaning heavily on the

arm of her husband. She wore an enamelled hair

locket around her neck and had a habit of rubbing

it with her plump white fingers, as if it was a tiny

lamp and she was trying to summon a genie.

She didn't seem interested in the tiny girls who

usually attracted the most attention. She didn't

glance at the capable big girls, almost ready for

work. We were used to strange women eyeing them

up and down, on the lookout for a useful servant.

No, this large lady in black always paused at our

table of ten-year-olds and hovered there, blinking

her shadowed eyes and fingering her locket. She

watched our every mouthful, she strained to hear

our whispered remarks, she peered with her large

head at an angle, as if she was Matron checking

the neatness of our plaits and the cleanliness of our

necks.

The large lady kept looking in our direction. Not

at me, but at Polly.

'That lady in black is really starting to annoy

me,' I grumbled. 'She will not stop staring. Poke

your tongue out at her, Polly!'

'Don't be unkind about her, Hetty. She looks so

sad,'

said Polly. 'Who do you think she can be?'

'Maybe she's your long-lost mother, come back

to claim you after all this time. She's rich and

respectable now and can afford to buy you back

from the governors,' I said.

'I think her husband

is

a governor,' said Polly.

'I saw him on Friday when the mothers were

petitioning. I remember his whiskers and his fat

watch-chain.'

'Look at the buttons on his waistcoat, all

set to pop off! Have you ever seen such a stomach!'

I said.

'But he looks a kindly man,' said Polly.

Perhaps he read her lips, because just then

he nodded at her and smiled. Polly smiled back

demurely. The lady in black gripped her husband's

arm and swayed a little, as if she felt faint.

'There! She's recognizing you, her little lost

Polly,' I said, carried away with my story.

I started elaborating on my romance, but

Polly wasn't listening. She was looking at the

couple and they were looking at her. It was almost

as if they were alone in the vast dining room. The

hundreds of other foundling girls did not seem to

exist – even me.

I felt my stomach tighten, so much so that I

could not finish my Sunday dinner. I was immensely

relieved when the table was tapped and it was time

to file out. I hurried Polly away from the couple,

suggesting we find a quiet corner to read – but

Matron Bottomly stood in the doorway.

'There you are, Polly Renfrew! Come with me to

my room, child.'

Polly gasped. There was only one reason for going

to Matron Bottomly's room. It meant that you were

going to be severely punished.

'But Polly hasn't

done

anything,' I said, taking

her hand.

'Did I ask for

your

comments, Hetty Feather?'

said Matron. 'Hurry along now, if you please.'

I had to slink away while Polly marched off after

Matron Bottomly. She peered back at me anxiously

and I gave her a cheery wave of encouragement,

though inside I was in turmoil.

I went off to the dormitory and waited by her

bed. I waited and waited and waited. Normally

Matron Bottomly was brisk with her punishments.

She'd give you a severe talking to. If you had been

exceptionally bad, you were whacked with a stick.

I was the only girl so far who'd been locked up in

the attic. She surely wouldn't dream of shutting

Polly

up there. Polly was so scared of the dark.

If she woke in the night, she always needed to

wake me up too so I could hold her hand. If she

was shut up alone in the attic all night, she'd go

demented. I was sure she hadn't done anything

wrong at all – though we were all used to being

seized indiscriminately and punished for some

insignificant or imagined offence.

I cast myself down on Polly's bed, beating it

with my fist in my frustration. 'I hate it here,

I hate it here, I hate it here,' I muttered into

Polly's pillow.

I shut my eyes tight, picturing myself marching

to Matron Bottomly's room and rescuing Polly – but

I so dreaded the punishment attic myself, I didn't

quite have the courage. I lay there, hating myself as

well as the hospital.

At long last I heard Polly's footsteps. I sat up and

stared at her. She wasn't flushed and tear-stained.

There were no cruel red marks on her hands. Yet

she looked immeasurably different. She was walking

slowly, as if treading water, and her eyes were dazed.

She blinked when she saw me.

'Oh, Hetty,' she said, and her hand went to her

mouth. 'Oh, Hetty, I hardly know how to tell you.'

I stood up and faced her. 'What

is

it, Polly?'

'I – I am leaving the hospital,' Polly whispered.

'What?' I said, shaking my head.

'I know. I can scarcely take it in myself, but it's

true. I've to gather up my things and go now. I am

to live with Mr and Mrs McCartney – she is the lady

in black.'

'Oh my Lord! Is she

really

your mother?' I said.

'No, no. She had a daughter our age, Lucy, but

she died of the influenza last winter and now she

wants to adopt me to take Lucy's place.'

'But people aren't allowed to adopt us! We belong

to the hospital.'

'I know, but Mr McCartney is a governor and a

very generous benefactor. They will do whatever he

wants,' said Polly.

'And – and is it what

you

want?' I asked

hoarsely.

'Oh, Hetty, I don't know!' said Polly, tears

suddenly rolling down her cheeks. 'I can't bear the

thought of not seeing you any more – but of course

I want to leave the hospital.'

'Do you

like

them, the McCartneys?'

'I think so. They seem very kind, though still very

sad. I am to have Lucy's room and all her clothes

and even all her toys. She has five large china dolls,

and a doll's house with an entire family of very little

dolls – a mother, a father, a grandmother with little

spectacles, a grandfather with a grey beard, and five

children, one a tiny baby doll in a crocheted shawl.

It was Mrs McCartney's when she was a child and

she described it very carefully. She gave it to Lucy

and now it is to be mine.'

'You are too old for dolls and doll's houses,' I

said sourly.

'I know, but I don't mind,' Polly said.

'

I

mind,' I cried. 'I mind it all. Oh, Polly, don't

go and be their child. Please stay here with me. You

are my only friend. I can't bear it at the hospital

without you.'

'I'm so sorry,' said Polly, hugging me. 'I haven't

any choice. Matron Bottomly says I have to go now.

But I will beg my new mama and papa to bring

me back here to visit you – and I will write to you

lots and lots. Then, when we are fourteen, we can

meet up properly because you will be out of the

hospital too.'

'Yes, but I will be a servant then,' I said. 'You will

be a lady.'

'We will still be

us,

Hetty,' said Polly.

But we knew there was already a divide between

us. I could not be mean enough to rebuke Polly

further. I knew I would have jumped at the chance

of escaping the hospital. I would not have sacrificed

that chance for anyone, not even my dearest friend.

But the McCartneys had not chosen me as their

new daughter. They had chosen Polly, and I could

understand why.

She was fair and neat and placid, while I was

small and fiery with flame-red hair. She had the

table manners of her spinster schoolteacher foster

mother: she cut up her food daintily, nibbled slowly

and drank from her cup with her little finger stuck

out at an elegant angle. I had the manners of a rough

country child: I still bolted my food and talked with

my mouth full and slurped my milk. Polly's voice

was gentle and she enunciated every word carefully,

while I spoke in a wild torrent. Of

course

they picked

Polly.

I swallowed hard, trying to compose myself. I

kissed her wet cheeks. 'I will miss you sorely, Polly,

but I am also truly happy for you,' I said.

'I'm sorry I've been so lucky,' said Polly,

still crying.

'I think those McCartneys are lucky having you

for their new daughter,' I declared.

We hugged again, and then I helped her

gather her few possessions. She insisted on taking

every present I'd ever given her, even the little

squashed heart with huge stitching. Matron

Bottomly came marching into the dormitory, rubbing

her hands.

'Are you ready, Polly dear?' she said, so

sickly sweet now that Polly was leaving. 'Mr

McCartney's carriage is waiting.

What

a fortunate

girl you are!'