Hetty Feather (21 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

I crept back to my own bed as soon as Eliza started

dozing, but I couldn't sleep. I lay there, crying, my

fists clenched. I felt so stupid. I'd believed every

word Jem had said. I'd loved him with all my heart.

I'd trusted him. I'd been so sure that he really would

wait for me.

'Oh, Jem, how could you repeat everything to

her

?' I whispered into my pillow. 'You're wicked,

wicked, wicked.'

But as the night wore on, I started to feel I was

being ridiculous. Jem hadn't been

deliberately

unkind. I knew he wasn't really a wicked boy. He was

a sweet, kindly soul who simply wanted to comfort

his silly little sisters. I could see it was ludicrous

for my five-year-old sister Eliza to talk of Jem as

her sweetheart and future husband. It was equally

ludicrous for me to think Jem truly wanted to marry

me. We'd both been little children. Jem was telling

us a fairy story to try to kid us we'd live happily ever

after. Of course he wouldn't marry either of us.

He'd remember us both fondly, if a little sadly.

Then, in the fullness of time, he'd fall in love with

some village lass like Nat's Sally and marry her. His

future was plain to me now. And my future was plain

too. I was Hetty Feather, a foundling, imprisoned in

the hospital. When I was fourteen, I'd leave to be

a servant. That was all I had to look forward to. I

would be a drudge for the rest of my days.

The hospital cook scalded her hands badly with

boiling water, and could not work for weeks.

Ida was asked to take over her duties until Cook

recovered. She was allowed to choose one of us girls

to help her in the kitchen. Ida selected the great

fourteen-year-old girls at first, as expected – but then

announced she'd like to give some of the younger

girls a chance.

'I'd like to try out Hetty Feather for a day,'

she said.

Matron Bottomly snorted derisively. 'You'll

regret

that

decision,' she said, but she let Ida have

her way.

All the other girls moaned and grumbled

and said it wasn't the slightest bit fair. I said

nothing at all. I stayed silent when Ida set me

to peeling the vegetables, freshly picked from

the hospital garden. She told me to have a little

nibble at the carrots and pod a few peas for myself,

but I didn't bother. I even shook my head listlessly

when she offered me a spoonful of syrup from

her larder.

'You're always hungry, Hetty! Aren't you feeling

well?' Ida said, putting her hand to my forehead.

'I'm all right. Leave me alone,' I said, shrugging

her hand away.

'Oh, Hetty, please, dear, tell me what's wrong,'

said Ida.

'Nothing!'

I snapped. 'Stop pestering me.'

If I'd spoken like that to Miss Morley or Matron

Bottomly, they'd have slapped me for impertinence,

but Ida just looked wounded. Her big blue eyes

blinked at me reproachfully. I felt bad because she

had always been so very kind to me – but I was

tired

of being kind back. I'd spent weeks making a fuss

of Eliza and listening to her endless prattle about

Jem when every word was a torment. I couldn't tell

her to shut up and keep out of my way. She was my

little sister after all. I knew just how sad and lonely

she was feeling, how very bleak the hospital seemed

after our cosy cottage.

When I'd first come here, it had meant so much

to me that Harriet had made a special pet of me.

I felt duty bound to do the same for Eliza, even

though the sound of her squeaky little voice made

me wince, and her habit of quoting Jem in each and

every sentence drove me to distraction.

I

had

to stop myself hurting her – but I didn't

see why I had to take such care with silly old Ida.

I wished she wasn't so stupidly sensitive. She had

spirit enough with the others. I'd seen her put Sheila

in her place often enough, and she was wonderfully

sharp with the nurses, even though forced to toady

to Matron Stinking Bottomly. Why did she have to

care what I said?

I sighed at her set shoulders and wounded

expression. She was making pastry, thumping her

rolling pin with unnecessary pressure. Ida had

introduced pies into our diet while Cook recovered,

and they were much appreciated by everyone.

I idly picked up all the cut-off ribbons of pastry. I

started to fashion them into a big fat dough lady.

I turned her into a matron with a silly cap and a

grim expression.

Ida stopped making her endless huge pies and

stared at my creation. She smiled, forgetting she

was offended. 'That's so good, Hetty!'

'No, it's not,' I said, and I suddenly squashed the

figure flat.

'Oh, look what you've done! I wanted to bake

it to keep her. My, you're in a bad mood today,

aren't you?'

I shrugged and made patterns in the spilled flour

on the kitchen flags with the toe of my boot.

'Don't do that, you're just treading it in,' said Ida.

She took a deep breath, still unaccountably intent

on humouring me. 'How about your taking a turn

with the pastry rolling?'

'I don't want to.'

'It's a skill to be proud of, making good pastry.

I've picked up a lot of knowledge working in the

kitchen. I could teach you all sorts, Hetty. Maybe

you could eventually get a position as a cook-general

if you learned a few recipes.'

'I don't

want

to be a cook-general,' I declared.

'It's far better than being a kitchen maid or a

tweeny.'

'I don't want to be any kind of stupid servant,' I

said.

'Especially

in a kitchen.'

This time I'd really gone too far. Ida flushed. She

thumped the pastry with her rolling pin. She looked

as if she'd like to give me a good thumping too.

'Oh, I'm all too well aware that you look down

your nose at servants,' said Ida. 'So pray tell

me, Hetty, what exactly

are

you going to do with

your life?'

I could not answer her. I had clung to the idea

of marrying Jem for so long. Now I could see how

painfully silly I had been.

'What was it again?' said Ida angrily, putting her

floury hand to her ear as if I'd spoken. 'Run away to

the circus to join your real mother?'

It was my turn to flush. I'd forgotten I'd once

told Ida about Madame Adeline. She was another

childish dream. I remembered the roar of the crowd

as we cantered around the ring, the sound of all

those many pairs of hands clapping me . . .

I stuck my head in the air. 'I might just do that

very thing,' I said.

'Oh, Hetty, as if that circus lady could

possibly

be

your mother!'

'She could be. She practically said so,' I said

fiercely. I did not really believe it now, but I could

not bear to let my last dream fade away.

'You're getting a big girl now,' said Ida, shaking

her head. She'd rubbed a floury sprinkle over her

cheeks and her cap was awry, making her look

foolish. 'You're far too old for these silly daydreams.

You've got to be practical, know your place, work

hard, make something of yourself.'

'Like you, you mean?' I said spitefully.

'You might not think much of my position,

Miss High and Mighty, but it suits me perfectly,'

said Ida. 'I work hard and I keep respectable and I

save my wages.'

'Yes, but what

for

? You do the same thing day

after day, week after week, year after year. You must

be mad, Ida. You don't have to stay here.

You're

not

a foundling. You could walk out and get a better job

anywhere.'

'I've got a good job

here

and I was very lucky to

get it too, coming from the workhouse,' said Ida.

'You're talking nonsense, Hetty. I know you must

be missing Polly sorely but there's no need to take it

out on me. I've tried my best to cheer you up.'

'I shall never be cheerful here, never never never,'

I declared.

I simply could not stop myself. Ida was my only

true friend left in the hospital and yet I seemed

determined to alienate her. I stayed rude and sulking

all day, doing the barest minimum of work.

'Judging by today, I doubt you can even be a

servant when you leave here, Miss Hetty Head-in-

the-Air,' Ida sniffed. 'No one in their right mind

would ever take you on as a skivvy, let alone a cook.

Now, are you going to snap out of it and be a good

sweet girl tomorrow?'

I snapped my fingers and then presented her with

my own glum face. 'Does it look like it?' I said.

'Well, go away and stew, you stupid girl. I'll pick

someone else to come and help me.'

'As if I care,' I said, and marched out of the

kitchen.

I cared dreadfully when Ida picked

Sheila.

I knew

she'd done it deliberately to annoy me. Ida didn't

like Sheila any more than I did. She just wanted to

pay me back. It was bitterly painful to peep through

the kitchen hatch and see Ida and Sheila stirring a

vat of rice pudding together, laughing away. When

Ida saw me looking, she popped a handful of raisins

into Sheila's grinning mouth. She gave a little nod,

as if to say,

That will show you, Hetty Feather.

It showed me all right. It looked as if I'd lost my

last friend at the hospital through my own stupid

behaviour. I should have gone to Ida privately and

apologized, but I was too proud. I stalked around by

myself, dutifully keeping an eye on little Eliza but

otherwise taking no notice of anyone.

I sat listlessly in the classroom, never bothering

to answer a single question now. I felt so dull and

slow I could scarcely lift my pen to write any words.

I found my grades slipping. I had been first equal

with Polly at everything, but now I was sliding down

almost to the bottom of the class, along with Mad

Jenny and Slow Freda and Stutter Mary, the three

sad girls who could barely read and write.

I tried even

less

with my household tasks. Every

Sunday I daydreamed in chapel and ate my dinner

stony-faced, staring down all the chattering ladies

and gentlemen. There seemed no point in smiling.

They would never pick

me

to be their new little

adopted daughter. I was small, sour, red-haired

Hetty Feather.

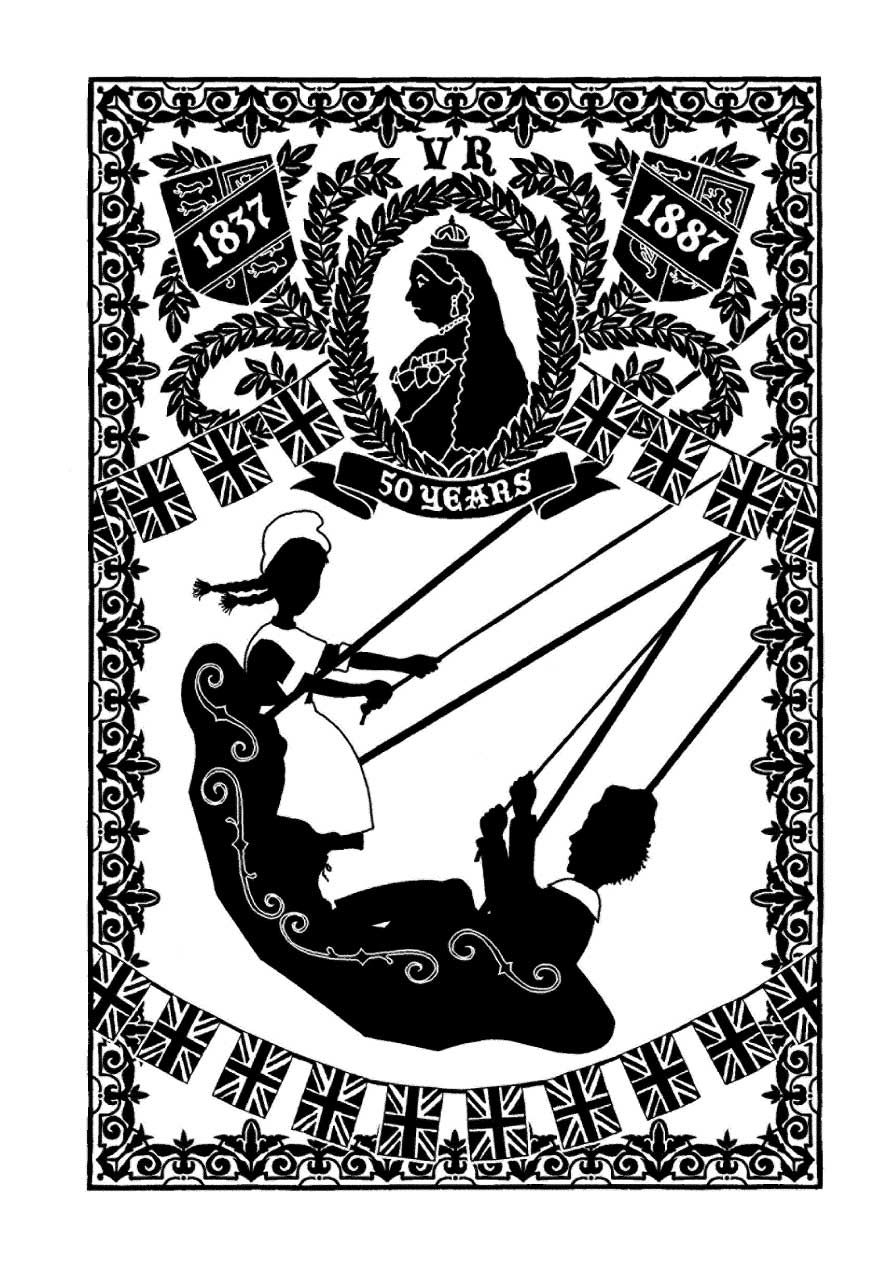

I could not even get interested when everyone

started talking about the Queen's Golden Jubilee in

June. What did I care for our fat little monarch? Miss

Morley's lessons became very focused on the Royal

Personage. At long last she used the coloured maps

on the classroom wall, showing us all the different

lands the Queen ruled over.

When she told us the Queen was also Empress of

India, half the class assumed she

lived

in that huge

hot sub-continent. Miss Morley laughed at such

ignorance. She said the Queen mostly lived here

in London, at Buckingham Palace – and she would

quite definitely be in London on 23 June, the day of

the Golden Jubilee.

Miss Morley seemed utterly obsessed with Queen

Victoria. She gave us dictation about our Loyal

Sovereign, she told us the history of her fifty-year

reign, she even had us calculating how many seconds

would tick by during the Royal Procession if it started

at eleven and ended at two. I assumed this was a

specific obsession peculiar to Miss Morley – but it

seemed to be shared by all the staff. Even little Eliza

started babbling about our Great Queen and showed

me a picture that she'd drawn in the infant class. I

admired it wearily, though her Queen Victoria looked

very like a fat stag beetle with a crown upon its head.

We even prayed for Queen Victoria in chapel

on Sunday, which seemed to me a little bizarre.

Why should all us foundlings, born in shame and

destined to live our lives as servants, pray for such

a fabulously rich and fortunate old woman who

owned whole continents? She should surely be on

her padded knees, praying for God's mercy for us.

At the end of the service Matron Bottomly

marched to the front of the chapel and ascended

the pulpit, her beaky nose pecking the air. She was

smaller than the vicar, so only her head was in view,

sticking up comically like a coconut on a shy. I had

such an urge to aim my hymn book at her!

'I have a very important announcement to make,

children,' she said. 'As you all know, our dear Queen

has ruled over us for fifty wonderful years. Next

Thursday is the day of the Golden Jubilee, when the

whole country will celebrate her glorious reign. We

are going to celebrate too! You have all been invited

to a festive gathering at Hyde Park in London. You

will be given a splendid meal at this venue and join

in all kinds of fun and games, and then Her Majesty

the Queen herself will come and greet you!'

There was a great

'Ooooh'

of excitement and

astonishment, though perhaps we were more thrilled

at the sound of the splendid meal and the fun and

games than the prospect of seeing the Queen.

I was excited too, I could not help it. We were going to

escape the dreary hospital for a whole day! Oh glory!

'Settle down now, children. You must be especially

well behaved. Any child who is seriously surly or

disobedient will

not

be included in the trip to see the

Queen,' said Matron Bottomly – and her ridiculous

coconut head turned so that she was looking straight

at me.

Oh, I understand you

very

well, Matron Stinking

Bottomly,

I thought.

It would give you such huge

delight to be able to deny me my rights. How it

would please you to declare before everyone that

Hetty Feather was too wicked to attend the Jubilee

Celebrations.

I smiled demurely back at Matron Bottomly. For

once in my life I wasn't stupidly going to cut off my

nose to spite my face. My behaviour over the next

few days was exemplary. I tried hard in lessons on

Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, but not

so

hard

that my knowledge irritated Miss Morley. I meekly

wrote down her exact words during dictation. I

figured out each silly sum, finding how many days

it would take Queen Victoria to sail to India if

her mighty ship steamed along at a certain terrific

rate of knots. I wrote a neat, unimaginative essay on

'What I should say should I meet Her Majesty the

Queen'.

I had myself performing copious curtsies,

simpering 'If you please, ma'am,' repeatedly. Miss

Morley gave me a big red tick and wrote

Excellent

at

the bottom of my page. She actually wrote

Excellant,

but I decided not to point this out. I sewed aprons

exquisitely, using tiny stitches and turning each

corner with a perfectly sewn double hem, as if I was

making the finest robes for the Royal Household. I

dusted every corridor and corner of the hospital, my

feather duster reaching

up

to the picture rails and

down

to the wainscoting. I practically lined up every

infant foundling and gave them a good dusting too.

Oh, how irritated Matron Bottomly must have

been when Thursday morning dawned bright and

sunny, and there I was, smiling, as good as gold. She

was probably tempted to give me a slap for sheer

cussedness. She did not have the imagination to

invent some wicked misdemeanour on the spot.

She simply gave me a hard poke in the back and

said, 'Mind your manners while you're out, Hetty

Feather. All of London will be looking at us.'

We were all issued with clean clothes from

top to bottom that Thursday, breaking with all

known custom. Our caps and aprons and tippets

were laundered and starched so snowy white they

looked brand new. Matron had had every big

girl ironing all day Wednesday, when we'd all

shuffled round in our stockinged feet while every

big boy polished our boots. We were given bread

and butter for our breakfast because the nurses

were so fearful the little ones might spill their

porridge down their crisp white chests. Every

child had mouth and hands dabbed at with a damp

cloth after breakfast, and all the infants were

forced into the privies and frightened into copious

evacuation so that none would disgrace the hospital

during our long outing.