Hetty Feather (24 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

'I

can't

go back! Oh, please, please let me stay

with you!'

'Dear child, I wouldn't be allowed to keep you.

Folk would say I had abducted you. They would

fear for your moral welfare here in the circus –

and rightly so. No, after the show I will accompany

you back to the hospital myself.' She looked at

a brass clock ticking on a shelf. 'I must start

getting ready now. Do you want to watch me one

more time?'

'Yes, of course!'

I thought she might send me out of the wagon

while she got ready, but she let me stay to watch

her transforming herself. She sat before her mirror,

placed the great red wig back on its stand, and tied

her own ruffled wisps back under a kerchief. Then

she applied greasepaint to her pale face, a thick

white, with bright pink on her cheeks. She put blue

on her lids and outlined her eyes with black kohl,

and then set her lips in a strange thin smile so she

could fill them in with carmine paint.

She went behind a screen, took off her dressing

gown and put on her pink spangled dress and white

tights. I heard her sighing and groaning as she

struggled into the tight costume and squeezed her

swollen feet into little pink ballet shoes. Then she

emerged self-consciously and carefully put the red

wig back on her head.

She stood before me, my Madame Adeline, ready

to pass muster in the circus ring, though now, close

up, I could still see the lines on her face under the

thick make-up, the sadness of her eyes beneath

her blue lids, the sag of her ageing body in the

unforgiving costume. I felt a fierce protective love

for her, as if she was truly my mother.

'You look beautiful, Madame Adeline,' I lied.

She gave me a kiss on the cheek and then went

to wipe the smudge of carmine away, but I protected

it with my hand, wanting to wear the marks of

my kiss with pride. She slipped her green dressing

gown round her shoulders and took me to the

entrance of the tent, open now, with people pouring

in to see the show.

'Make sure this child gets a good seat,' she said

to one of the circus hands. 'I will come and collect

her after the show to take her back home.'

She went off with one last wave to me. I sat in the

front, waiting tensely, while the audience chatted

and chewed food and started calling out impatiently

for the show to start.

Then Chino came capering into the ring, followed

by his clown friend, Beppo. Everyone laughed at

their foolish antics, but now that I knew Chino

was just a sad old man doing his job I could not

find him funny. I did not even enjoy it when he ran

rings round Elijah the elephant and performed the

clockwork-mouse trick. I could not marvel at Elijah

either as he wearily performed each plodding trick,

his skin sagging, his tiny eyes half blinded by the

bright flare of gaslight.

I watched the lady walking the tightrope, grown

very plump, though she was still as nimble dancing

up in the air. I saw the silver-suited tumbling boys,

three of them now, one as small as me. I wished

Gideon was with me to see them leap and cartwheel.

I saw the gentleman throwing daggers at the lady,

the seals clapping their flippers, the man eating fire.

It was as if they were all phantoms in a dream. I

had pictured them vividly so many times, glorifying

everything, so that now their real acts seemed a dull

disappointment.

'Now, ladies and gentlemen, girls and boys,

Tanglewood's Travelling Circus is proud to present

Madame Adeline and her rosin-backed performing

horses!'

I sat up straight, fists clenched, scarcely able to

bear the tension. Madame Adeline came cantering

in on a piebald pony, another following close

behind. The two horses stepped in time to the

music, sometimes hesitating and missing the beat.

They were old now, their manes yellow-grey, their

flanks sunken.

Madame Adeline stood up on the back of the lead

horse, straight and proud as ever, smiling with her

carmine lips. I watched her perform every trick,

leaping precariously from one horse to another,

swinging her legs, standing on her hands, jumping

through hoops – my heart in my mouth in case she

slipped.

'Hello, children,' she called. 'Who would like to

come and ride with me?'

She looked straight at me and beckoned. I had

to go to her. I felt foolishly conspicuous in my ugly

brown frock. Small though I was, I was clearly the

eldest child scrambling into the ring.

Madame Adeline smiled at me and helped me

up onto the first piebald horse, swinging herself

up after me. We trotted round the ring while

everyone clapped.

'Shall we perform properly for them, Hetty?'

Madame Adeline murmured into my hair.

'Yes, yes!'

Madame Adeline clucked and our horse gathered

speed, galloping round and round the ring while I

grabbed his mane and dug my knees in hard to keep

my balance.

'Your star turn now!' said Madame Adeline.

'Time to stand up.'

It was much harder now that I was taller

and Madame Adeline not so strong. I wobbled

precariously, trying desperately to keep my boots

connected with the horse's back. I could only

manage a split second before I collapsed back onto

the horse with a bump – though everyone still

clapped.

We slowed down and I scrambled off inelegantly,

terrified that folk would see I wore no drawers.

Madame Adeline held my hand and we took our bow

together.

'Well done, dear Hetty,' she whispered. 'Watch

the rest of the show and then I will come for you to

take you back.'

I smiled and nodded at her – but after she'd left

the ring I stood up and sidled my way along the row

to the end. I slipped out of the tent.

'Goodbye, dear Madame Adeline!' I whispered,

blowing a kiss in the direction of her wagon.

I could not return to the hospital and the terrible

punishment attic. I had run away for ever. I had to

fend for myself now.

I stepped out purposefully, though I had no idea

where in the world I was going. The fairground

smell of onions and fried potatoes made my mouth

water. I had no money – but I watched a finicky lady

nibble at a cone of fried potatoes, pull a face and toss

them to the ground. I darted forward and snatched

them up. I wolfed them down hurriedly. That was

supper taken care of.

It was starting to get dark, so now I needed a bed

for the night. I wandered past the noise and glare

of the fairground onto the wild heath. At first there

were still couples all around me, strolling through

the trees, rustling and giggling in the bushes, but

after five or ten minutes' walking I seemed to be all

alone. I knew the heath wasn't proper countryside,

but it had the same good fresh earthy smell.

I stared up at the stars and moon, marvelling in

spite of my desolation. I had not seen the night sky

properly since I was five. I held my arms up as if I was

trying to embrace the constellations. I remembered

Jem naming some of the stars for me, and my eyes

filled with tears. I knuckled them fiercely. I had

done enough crying for today. I had to be practical

and find a safe place to sleep.

In the dark I could not find a hollow tree to

turn into a squirrel house, so I found a large bush

instead. The ground felt dry and sandy underneath.

I crawled under the thick branches and curled up in

a ball, cradling my head with my hands.

'This is

better

than a squirrel house,' I told myself.

'This is a cosy little burrow, and if I shut my eyes I

shall picture it properly.'

I pictured a sweet bedchamber with a patchwork

quilt of buttercups and daisies and clover. It was

very similar to the illustration of the field-mouse's

burrow beneath the cornfield in my

Thumbelina

storybook. Oh, how I wished I had my precious gift

from Ida with me now. However, I'd read it so many

times I knew the story almost by heart. I repeated

it to myself – and by the time Thumbelina flew off

with her swallow I was fast asleep.

I woke with a start in the middle of the night,

cold and stiff and terrified. I could not make my

picturing work now. I felt utterly alone, like the last

child left on earth. I could not stop myself weeping

then. I went back to sleep wondering if I might not

even be better incarcerated in the punishment attic

of the hospital.

I felt more cheerful when I woke in the soft

summer daylight. I rolled out from under my bush,

stretched heartily and strolled about. I had no privy

but it was easy enough to squat behind a tree. Now

I needed a washroom. To my delight I found a series

of ponds, gleaming silver-grey in the early sunshine.

I had no idea how to swim, but I took off my boots

and stockings and dress and had a quick splash in

the shallows.

I had no towel to dry myself so I ran madly all

the way round the pond, and when I came back to

my clothes I was nearly dry. I smoothed the creases

from my dress as best I could, and polished the dust

from my boots with a clump of leaves. I let my hair

loose, combed it with my fingers, and then replaited

it as neatly as I could.

Now I needed breakfast! This was more of a

problem. I wandered around looking for nuts or

berries but I could not find any at all. Perhaps if I

found my way back to the fair I'd be able to forage

for thrown-away scraps? But I'd wandered so far

now I had no sense of direction. I simply walked

on,

not sure whether I was heading north or south, or

simply going round in circles.

I saw a blue wisp of smoke coming from a small

copse, and as I drew nearer I smelled a wonderful

savoury cooking smell. I crept closer and came upon

a group of dark gypsies in strange bright clothes

frying some kind of meat. I wondered if they might

share their meal with me. For a few seconds I even

had a fantasy of becoming a gypsy girl and travelling

in their caravan and selling clothes pegs and telling

fortunes, but their dog barked at me furiously and a

ragged child started hurling stones at me.

They were clearly not making me welcome so

I wandered on, hungrier than ever. I reached the

edge of the heath at last and walked out onto the

pavement, feeling strangely disorientated to be

back in the town so rapidly. I kept my eyes peeled

for dainty ladies throwing away half-eaten food, but

there were mostly gentlemen in the streets, walking

quickly, glancing at their watches, running to catch

omnibuses, obviously off to work.

I walked on and on, peering in at the windows of

all the big grand houses. I could sometimes see right

down into the basement kitchens, with servants

scurrying around.

'I am

never

going to be a servant,' I said to myself,

trying to lift my spirits. 'I am Hetty Feather and I

am not taking orders from anyone. I am as free as

the air. I can go anywhere. I can do anything. I can

totally please myself.'

But my spirits still seeped right down into my

hard boots, and I was snivelling as I walked, unable

to control myself. I was so tired and light-headed

I sank to the ground, leaning against someone's

wall. I covered my face with my hands so that folk

passing by would not see I was crying. Then footsteps

paused in front of me. Something landed in my lap.

Oh Lord, was this another child throwing stones? I

took my hands away from my eyes – and stared at a

big bright penny shining on the brown stuff of my

dress. I looked up and a kindly-looking lady nodded

at me.

'There, dearie,' she said, and went on her way.

She thought I was a beggar child! My face flamed

red – but my hand grasped the penny.

'Thank you so much, ma'am,' I called after her.

Perhaps her gesture inspired the other passers-

by. Maybe they hadn't even noticed me before. But

now my tear-stained face attracted attention, and

another penny soon landed in my lap, a farthing,

and then a halfpenny, soon a whole jingle of copper

coins.

Oh my Lord, this was easy! I could sit here at

my leisure and look mournful and folk would pay

me! But then I saw a dark-uniformed man in the

distance, a helmet on his head. I was pretty sure he

was a policeman. I was also pretty sure that begging

was against the law.

I gathered my coins into my fist, scrambled up

and ran off as fast as I could. I careered down long,

long roads of houses, my throat aching, my heart

jumping in my chest, not even daring to look round

in case he caught me. I feared the police had prisons

and I did not want to end up in a cell.

Then I came to a parade of shops and dared to

pause at last. The policeman was nowhere in sight.

I loitered in front of every shop window, and then

came to a stop outside a baker's shop. The smell of

freshly baked bread brought a flood of water to my

mouth and I felt faint.

I stared at the cakes and buns on display in the

window. There were slabs of the pink and yellow

cake, Madame Adeline's favourite, and white-iced

fancy cakes, and red and green and yellow jam tarts,

and all manner of golden latticed pies and glazed

buns, shiny and soft and curranty.

I had no idea how much such wonders would cost.

They could be sixpence each, even a sovereign for

all I knew. Perhaps the woman in the white apron

inside the shop would scoff at my impertinence if I

proffered my small handful of coins. But I was so

hungry I decided to risk it.

I opened the door and stepped inside. 'If you

please, ma'am . . .' I started shyly.

'Yes?'

'I – I'd like to purchase a little cake – or maybe

a bun?'

'Well, make your mind up, dear,' she said, but she

didn't sound too impatient.

'Perhaps a cake, the pink and yellow one –

and

a

bun?' I suggested, and then I anxiously showed her

my coins. 'Do I have enough money?'

'More than enough, dear.'

She put my cake and bun into a white paper bag,

twirled it round so that the corners were twisted

fast, took twopence halfpenny from my hand, and

gave the bag to me.

'Thank you kindly, ma'am,' I said.

She laughed a little then. 'You've got the best

manners of any street child I've ever come across

before!' she said. 'Goodbye, dear. Take care of

yourself.'

I

could

take care of myself! I had found a place to

sleep, a place to wash, I had earned lots of money,

and now I could breakfast like a queen! I ate my cake

and bun, and when I came to a tea stall I bought

myself a large mugful for another penny. Then I

went marching on, refreshed and renewed, peering

all about me.

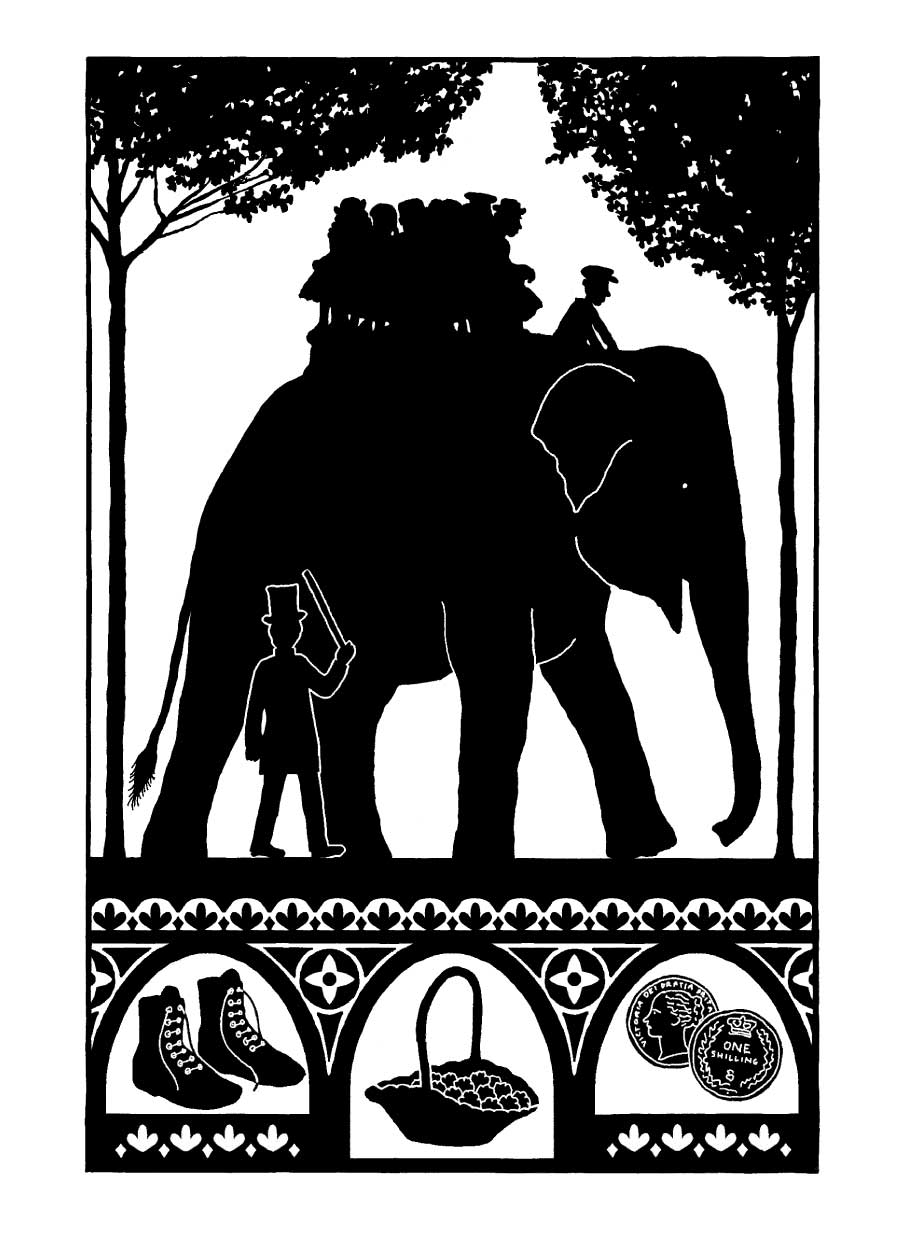

I found myself wandering in more huge parkland.

For a moment I thought I was back in Hyde Park

because I heard an elephant trumpeting – but

I discovered I was near the Zoological Gardens. I

peered through the railings and saw an elephant

even larger than Elijah with a curved seat on his

back. Ten or twelve children were strapped onto the

seat, while another boy rode bareback on his neck,

his boots nudging the beast's great ears.

I had a desperate desire to ride an elephant too!

I paid sixpence to get into the zoo, and another

twopence for a ride. This was the last of my money

so I very much hoped the ride would be worth it. I

queued impatiently at the landing stage amongst a

great crowd of girls and boys, waiting until at last

it was my turn to be hoisted onto the great grey

creature.

'I am very good at riding. Please may I sit on the

elephant's neck?' I begged the keeper.

'Don't be silly, missy – you're a young lady,'

said the keeper, and he put one of the boys on the

elephant's neck.

The boy nodded at me triumphantly, pulling a

silly face. Other boys shrieked and squirmed beside

me, jostling for the best position on the seat – but I

was adept at elbowing my way when I wanted. One

of the other girls was hopelessly squashed, however,

with two rude boys practically sitting on top of her.

'Move next to me,' I said.

She smiled at me timidly. She was beautiful, just

like a fairy-tale princess, with big blue eyes, rosy

cheeks and long golden curls. She wore a cream silk

hat and a matching silk dress, with white stockings

and white kid boots with tiny blue buttons.

'Come on, wriggle past those silly boys,' I said,

reaching out and grabbing her.

She squeezed past them and I pulled her

safely down next to me. I could feel her trembling

violently.

'What's the matter?' I asked in astonishment.

'I'm frightened!' she said.

I didn't know if she was frightened of the elephant,

frightened of heights, frightened of the rude boys, or

simply frightened of getting her pretty pale clothes

dirty. I reached out and held her hand.

'There now, no need to be frightened. I will look

after you,' I said. 'My name's Hetty. What's yours?'

'I'm Rosabel,' she said.

I sighed. Trust her to have a beautiful name

too!

The elephant was fully loaded now, so the keeper

gave him a little tap and we set off, plodding down

the path. The boys shrieked loudly and Rosabel

clutched me as if she would never let me go.

'Oh dear, it's so scary! I wish the beast wouldn't

roll

so,' she gasped. She peered down desperately.

'I've lost sight of my mama and papa. Can you see

yours?'

I would have a hard job seeing either!

'I am here on my own,' I said proudly.

'Without even your nurse?' said Rosabel.

'I don't have a nurse any more,' I said. 'I am too

big.'

'No you're not, you're little, much smaller than

me,' said Rosabel. 'Oh,

there

is Mama. I see her

lilac parasol!' She risked letting go for a second,

attempting a little wave.

I stared at her mother. 'She is very young and

beautiful,' I said wistfully.

Her papa was waving too. He looked a kindly,

jolly man, with a pink face.

'Papa is pleased with me for taking the elephant

ride. He feels I am too timid,' said Rosabel. 'But

Mama says all girls are naturally timid.'

'I'm a girl and I'm not the

slightest

bit timid,' I

said.

'Perhaps we could be friends and then you could

teach me how to be bold and independent,' said

Rosabel.

My heart leaped. Maybe Rosabel's family would

take me under their wing? I could be a devoted

companion to their little daughter! They might

even adopt me like Polly. I wasn't sure I should be

happy wearing cream silk dresses and fancy hats

and white boots. I knew how dirty they would be by

the end of the day. Maybe they would let me choose

a darker colour for my clothes, red or blue or purple

–

any

colour so long as it wasn't sludge-brown. I

didn't hunger after dolls and toys but I was sure a

cosseted child like Rosabel would have a whole shelf

of storybooks – and I could share them.

I was still eagerly picturing my future with

Rosabel as the elephant plodded back up the path

to the landing stage. I kept hold of Rosabel's hand

and helped her down carefully.

'Rosabel! Over here, my dear!' both parents

called.

I trotted over with her, but the mama suddenly

looked horrified and even the papa appeared grave.

'Say goodbye to the little girl, dearest,' said the

mama, very firmly.

'She is my new friend Hetty,' said Rosabel.

'Don't be ridiculous, Rosabel. She is just a dirty

street child. Leave go of her hand. You should never

have let her get so near to you!' said the mama.

The papa turned on me. 'Be off with you,' he said,

swotting at me.

If they thought I was a street child, I would

act like one. I stuck out my tongue and waggled it

hard before running away. My feelings were hurt

nevertheless, but I diverted myself by inspecting

all the creatures in their cages: the scampering

monkeys, the pacing lions, the savage bear in his

pit. I felt sorry for all these poor caged animals. I

wanted to set them free so that the monkeys could

snatch up all the flimsy parasols, the lions could

leap at all the scornful parents and the bear maul

them to pieces.