Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet (19 page)

Read Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet Online

Authors: Frances Moore Lappé; Anna Lappé

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Political Science, #Vegetarian, #Nature, #Healthy Living, #General, #Globalization - Social Aspects, #Capitalism - Social Aspects, #Vegetarian Cookery, #Philosophy, #Business & Economics, #Globalization, #Cooking, #Social Aspects, #Ecology, #Capitalism, #Environmental Ethics, #Economics, #Diets, #Ethics & Moral Philosophy

Part III

Diet for a

Small Planet

Revisited

1.

America’s Experimental Diet

T

O

EAT THE

typical American diet is to participate in the biggest experiment in human nutrition ever conducted. And the guinea pigs aren’t faring so well! With a higher percent of our GNP spent on medical care than in any other industrial country and after remarkable advances in the understanding and cure of disease, the life expectancy of a forty-year-old American male in 1980 was only about six years longer than that of his counterpart of 1900.

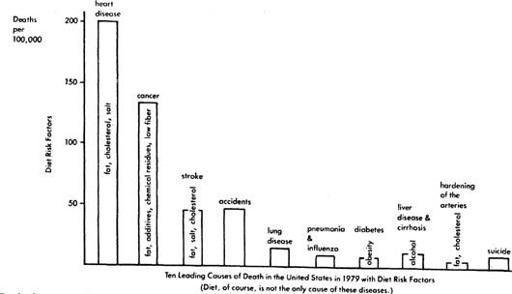

Why haven’t our wealth and scientific advances done more for our health? Medical authorities now believe that a big part of the answer lies in the new American diet—an untested diet of high fat, high sugar, low fiber, which is now linked to six of the ten leading causes of death. (See

Figure 4

.)

The first two editions of this book are full of nonmeat recipes, just as this one is. But in my discussion of nutrition I stuck to the protein debate because I wanted to demonstrate that we didn’t need a lot of meat (or any, for that matter) to get the protein our bodies need. Now I think I missed the boat, for the

Diet for a Small Planet

message can’t be limited to meat. At root its theme is, how can we choose a diet that the earth’s resources can sustain

and

that can best sustain our bodies? To answer that, I had to investigate more than meat.

Figure 4. Impact of the Experimental American Diet

As I looked at the radical change in the American diet, I was most struck by our soaring meat consumption. In my lifetime beef consumption has doubled and poultry consumption has tripled. What I didn’t adequately appreciate was how much our

entire

diet had been transformed. In the 1977

Dietary Goals for the United States

, health authorities summing up information gathered by the Senate Select Committee on Health and Nutrition concluded that Americans are eating significantly more fat, more sugar, and more salt, but less fiber and too many calories. No fewer than 16 expert health committees, national and international, now agree that each of these changes is linked to heightened risk of disease.

1

Many other people are concerned that the food additives and pesticide residues we are ingesting may also pose health hazards.

Most striking is that each of these health-threatening dietary changes is actually a byproduct of two underlying ones:

more animal food

, and

more processed food

. “Processed” simply means that between the ground and our mouths someone takes out certain things and puts in other things—and not always things that are good for us. The problem is not that Americans are adding more sugar and salt to their recipes or cooking with more fat; the problem is that these are being added

for

us. All we have to do is take the fatty, grain-fed steak from the meat counter, the potato chips from the shelf, or the Big Mac from its styrofoam package.

Eat at Your Own Risk

You’ll notice that when scientists speak of diet and disease they are careful to say that such-and-such a way of eating affects the “risk” of getting a particular disease. That’s because it is almost impossible to

prove

that diet causes a particular disease. For instance, you can’t prove that your father’s heart attack was caused by high blood pressure that was caused by his high salt diet.

Scientists must largely rely on “guilt by association.” By comparing populations, they can observe which diets are associated with which types of disease. But comparing different societies with different diets is less than convincing, since there is always the possibility that genetic differences among populations and other environmental factors play a decisive role. So the most telling observations are those of a single population group which changes its diet. Here is a sampling of such evidence:

• The traditional Japanese diet contains little animal fat and almost no dairy products. Japanese who migrate to the United States and shift to a typical American diet have a dramatically increased incidence of breast and colon cancer.

2

• The citizens of Denmark were forced to reduce their intake of animal foods by 30 percent during World War I, when their country was blockaded. Their death rate simultaneously fell 30 percent, to its lowest level in 20 years.

3

Denmark’s experience was not unique: in a number of European countries, where World War II forced people to eat less fat and cholesterol and fewer calories, rates of heart disease fell.

• In some third world countries a small class of urbanites have adopted the new American diet over the last 20 years. Coronary heart disease now occurs more and more frequently in some of those countries, such as Sri Lanka, South Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines, the World Health Organization reports.

4

Other important evidence comes from different diet and disease patterns in populations that are similar in most other ways. For example, a study of 24,000 Seventh Day Adventists living in California showed that the nonvegetarian Adventists had a three times greater risk of heart disease than those eating a plant food diet.

5

In her fascinating, thoroughly researched book

Jack Sprat’s Legacy

(Richard Marek, 1981), Patricia Hausman convinced me that health authorities around the world virtually all agree: the typical American diet is a high-risk diet. The “debate” over the risks associated with the new American diet is perpetuated by the media and vested interests in the meat, dairy, and egg industries, who have spent millions of dollars trying to publicly deny these risks, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Eight Radical Changes in the U.S. Diet

The food industry was quick to attack the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs for daring in 1977 to suggest a change in the American diet. How ironic. Never has a people’s diet changed so much so fast as ours has over the last 80 years. And that change, as we shall see, has been in large part caused by the food industry itself.

I have looked at each of these changes and asked, what are the risks associated with this change? And

why

the change? (By the way, the best detailed source on the “Changing American Diet” is an excellent book by that name (1978) written by Letitia Brewster and Michael Jacobson of the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington, D.C.)

I will discuss each change separately, but as nutritionist Dr. Joan Gussow wisely observes, our bodies don’t experience these changes separately. “One of the handicaps of most ‘scientific’ investigations of the impact of dietary change is that each is studied separately, whereas the greater threat may be their cumulative impact,” says Dr. Gussow. So we have to look at the whole cluster.

Dangerous Change No. 1: Protein from Animals Instead of Plants

Contrary to what I thought, the dramatic change is

not

in our protein consumption. It has actually varied little over the last 65 years, fluctuating between 88 grams and 104 grams per person per day (roughly twice what our bodies can use). The change is in how our protein is packaged. Sixty-five years ago we got almost 40 percent of our protein from grain, bread, and other cereal products. Now we only get 17 percent of our protein from these sources. In their place, animal products, which then supplied about half of our protein, now contribute two-thirds.

6

U.S. consumption of animal products began to climb after World War II, with beef consumption almost doubling and poultry consumption almost tripling by the late 1970s.

7

T

HE

R

ISKS

There is no medical consensus about the risks of diets high in protein generally or about diets high in animal protein specifically. (There is general agreement about the risks of what results from this new “packaging” of our protein—more fat and less fiber. But I’ll deal with those risks later.) While no consensus exists, there are some intriguing warning signals.

The Senate Select Committee notes: “One series of investigations found that diets that derive their protein from animal sources elevate plasma cholesterol levels to a much greater extent than do diets that derive their protein from vegetable sources. Another line of basic research demonstrated that, in almost all cases, high protein diets are more atherosclerotic than are low protein diets.”

8

(Atherosclerosis is a hardening of the arteries caused by fatty deposits accumulating along the artery walls.)

High-protein diets have also been linked to osteoporosis, the thinning of the skeleton, in some studies. Osteoporosis, which now affects four out of five elderly American women, occurs when calcium is drawn from the bones, weakening them. Pain, fractures, and even the collapse of part of the vertebrae can result. Because more calcium is excreted in the urine in a high-protein diet, this kind of diet may promote osteoporosis. (Apparently, eating more calcium doesn’t help.) One recent investigation found that animal protein did contribute to increased calcium excretion. But there is still much that’s not understood.

9

Dangerous Change No. 2: More Fat

Americans eat 27 percent more fat than did our grandparents in the early 1900s. And more than one-third of that increase has come just in the last ten years. As a result, fat’s contribution to our total calorie intake climbed from 32 to 42 percent, though there are signs that the average may be lowering.

T

HE

R

ISKS

The risks appear to lie in too much total fat, too much saturated fat, and too much cholesterol. Saturated fats, found in animal foods and in some vegetable foods (especially palm and coconut oil), and cholesterol, found only in animal foods (especially eggs, some seafood, and organ meats), generally increase the blood cholesterol level. Eating saturated fat raises blood cholesterol levels more than does eating cholesterol itself.

10

As Patricia Hausman explains in

Jack Sprat’s Legacy

, the higher the blood cholesterol, the greater the rate of fatty deposits that harden the arteries. The more severe the fatty deposits in the arteries, the greater the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other complications of atherosclerosis.

Reducing the cholesterol in the diet does not automatically reduce the cholesterol in the blood for everyone. There may be genetic factors which determine why some people respond to lowered dietary cholesterol and others do not. But to be on the safe side, it would seem prudent to assume that lowering our cholesterol consumption will make a difference.

In a survey of 200 scientists in 23 countries, 92 percent recommended that we eat less fat to reduce our risk of heart disease.

11

In addition to increased risk of heart disease, says Hausman, “studies, spanning up to 40 countries worldwide, confirmed that the total amount of fat in the diet does correlate with some forms of cancer. Studies link six forms of cancer with dietary fat, including cancers of the breast and colon, two of the top cancer killers in the United States.”

12

Dietary Goals for the United States

suggests we return to a diet in which 30 percent of our calories come from fat, instead of the 42 percent we’re averaging now. (The Japanese, notable for their low incidence of heart disease, traditionally have gotten only 10 percent of their calories from fat. Unfortunately, this is rapidly changing as hamburger joints displace the traditional rice, fish, and noodle bars.)

The good news is that eating polyunsaturated fats—safflower, sunflower, corn, and soybean oils—actually

lowers

the blood cholesterol levels, and may help control hypertension as well.

13

So the recommendation is that at the same time as we reduce our total fat, we shift from animal fats and palm and coconut oils to more of these polyunsaturates.

W

HERE

I

S THE

F

AT IN

O

UR

D

IET

?

We are eating more fat, not because we are pouring more oil on our salads or frying more foods at home. Again, we are letting someone else ut the fat in for us. In our “choice” and “prime” steaks, grain has been turned into fat. In those french fries at Burger King, a very low-fat food—the potato—has been transformed into one in which most of the calories are from fat, mostly saturated fat.