How to rite Killer Fiction (14 page)

Read How to rite Killer Fiction Online

Authors: Carolyn Wheat

How about her lost voice? How does our Manhattan mermaid become unable to speak because she made a bargain with a magician to win her prince?

This book begins with a prologue showing our heroine on her way to the prince's secret cabin in the woods (okay, we're sneaking into Bluebeard territory here) to open the Door That Must Not Be Opened. She has tools with her, obviously intended to effect her entry into the cabin, and as she passes the winter-bare trees she nails bits of cloth to them for markers so she can find her way back (recalling Hansel and Gretel). As she walks she thinks about going to the sheriff: "But he would surely refuse to help and would simply stare at her with that familiar look of speculative disdain."

The town belongs to the prince. Any time she voices the slightest doubts about the prince or raises a question about the dead wife, she's met with the same blank stares, the same robotic assurance that there's nothing wrong. As far as making herself heard, she might as well have no voice because nothing she says is listened to or acted on. (Of course, being from Manhattan makes her doubly suspect.)

The worst part is that her own daughters stop listening to her. They love their new house and new life and the horses and the kindly prince and to them our heroine begins to seem like a wicked stepmother intent on depriving them of joy.

This time the Little Mermaid

can

undo the bad bargain she made. Borrowing from Bluebeard's brave wife, she opens the Door That Must Not Be Opened and lets all the secrets out, and that power is what allows her, at long last, to be heard. That and one very unexpected ally: the ex-husband (just think of him as the dwarf who got away).

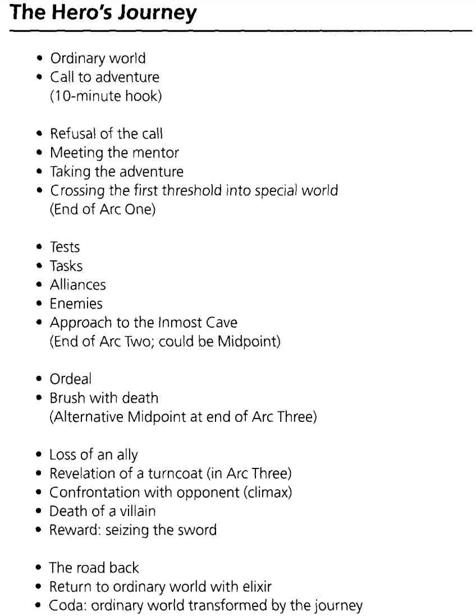

The Hero's Journey_

Joseph Campbell died in 1987. He's not writing movies in Hollywood, but sometimes it seems as if his spirit infuses many screenwriting classes these days. Whether it's an interior journey like the one in

A Beautiful Mind

or a blockbuster explosion-riddled thriller like

Independence Day,

we love seeing the hero's journey over and over again.

What is the journey, and how does it inform suspense writing?

Our hero begins his journey in the ordinary world. This is Cinderella's house before her father remarries, or, in T. Jefferson Parker's

Little Saigon,

hero Chuck Fry's world before his brother's wife is kidnapped. Some external event forces change and decision, and pushes the hero out of the ordinary world into a special world where new realities, new rules, must be learned, and where there will be tests and tasks to be mastered.

The Little Mermaid's special world is our ordinary one, because her ordinary world lies under the sea. Clark's heroine is taken from her ordinary world of Manhattan to the special world of her prince's domain; Fry's special world is that of the Vietnamese exiles. Even though they live in Orange County, California, and he makes no physical journey to find them, their world is alien to him. Accepting the adventure and crossing into the special world marks the end of Arc One and the beginning of the big bad middle.

The middle of the story is where the growth occurs. Here the hero meets allies and learns to distinguish (through trial and error) between those he can trust and those he can't. Tests and tasks abound, skills are learned, a mentor gives direction (in

Little Saigon

a Vietnamese elder helps Fry understand some of what's going on), and the hero moves inexorably toward a direct confrontation with evil.

Evil may reach out and harm the hero, but eventually, he must move in the direction of the evil instead of running away. Once freed from police custody, the Fugitive (in the movie of the same name) doesn't hop a plane and go to Peru, he marches straight into the very hospital where he once practiced, risking being seen and captured, in order to find the one-armed man. When the Wizard of Oz tells Dorothy to get a straw from the Wicked Witch's broomstick, she doesn't shrug and say, "I guess I can't get home then"; she sets off toward the witch's castle to do what has to be done. When Clark's mermaid finds out about The Door That Must Not Be Opened, she steels herself to open it, no matter what the consequences. The cops, the Vietnamese, and Fry's own brother and father all beg him to stay out of the kidnapping case, but he doggedly continues his quest for the truth that will free his sister-in-law.

These heroes enter the Inmost Cave, the most dangerous place they can be, the heart of their enemy's power, because they must. And they encounter death. Snow White "dies" when she eats the poisoned apple; Jenny McPartland is urged to "become" her dead predecessor; Fry faces death when he's pitted against ruthless Vietnamese gangsters.

The ultimate confrontation pits good against evil. Good wins, but we're never quite sure it's going to, and we never know exactly how our innocent and seemingly less powerful hero will find the tools and the heart to prevail.

What heroes win is the elixir, a fancy name for their new knowledge, their hard-won insights and maturity. In

A Cry in the Night

, it's the knowledge that our heroine, like the Little Mermaid, gave up too much of herself for her prince. In

Little Saigon

, the elixir is Fry's reconciliation with his family.

In some books, there's also a sacred marriage. Not only has Clark's heroine escaped her Bluebeard of a prince, but the local vet will make a wonderful real prince and he won't ask her to wear another woman's identity in order to be loved.

Well, okay, that's a chick book. How does all this fairy-tale stuff fit into a suspense novel with masculine energy?

Little Saigon,

T. Jefferson Parker

Once upon a time there were three brothers, and the youngest was called Simple.

Actually, in this book there are two brothers. The older, Bennett, is a Vietnam veteran, brave and strong, his father's right-hand man, responsible and married to a beautiful Vietnamese woman. He's the hero, right?

Wrong. His younger brother, Chuck, the family screw-up, the second-best surfer in Laguna Beach (that second-best theme is going to come up again), the boy who caused his little sister's drowning, the man who lives in a cave-house and runs a tacky surf shop instead of working in the family business—he's the hero and it's his transition from aging boy to mature man that we're going to experience.

Chuck goes through the same maturation process as Jenny McPartland. He's tested by the search for his sister-in-law; he meets a mysterious woman with secrets of her own and has to decide whether to trust her or not; he's helped by an elder in the Vietnamese community, and then that elder is murdered before his eyes.

By the end of the book, he's become a man instead of a boy; he's matched his heroic brother in his ability to go head-to-head with vicious, violent killers and emerge triumphant. Without the testing process, he'd still be second best.

The Night Manager,

John Le Carre

Here's a perfect example of the middlebook as training ground. The title character begins the story as the night manager of a hotel in Cairo. When someone he cares about is ruthlessly killed by bad guys, he lets himself be recruited by British intelligence. His decision to join the team is Plot Point One and his training and first tasks comprise Arc Two.

Arc Two takes the character from raw recruit status to the successful completion of the first task, which also sets up his cover for the ultimate goal, infiltrating the Big Bad Guy's entourage. Task two takes our hero from England to Canada and further away from his ordinary world. By the time he creates the scenario that allows him entry into the world of the Big Bad Guy, we believe that a man whose biggest concern used to be whether or not the presidential suite was ready is capable of bringing down the Big Bad Guy because we've seen him master smaller but still impressive tasks. He's earned the right to play the big time.

Arc Three gives us the infiltration itself. Now he's in the Cave, in this case the tropical island compound and yacht belonging to the Big Bad Guy. He's in a great position to grab up all the secrets and blow this guy's world apart, and all he has to do is not be found out because the moment he's found out, he's a dead man. Every cocktail party, every walk on the beach, is fraught because allies of the Big Bad Guy don't trust him and are working to expose him.

Then he falls in love with the Big Bad Guy's girlfriend. He's in the frying pan already, and Le Carre turns up the heat.

Psyche's Journey to Hades_

The kinds of tests and tasks the hero performs in the middle of a suspense novel resemble the ordeal a goddess of ancient Greece devised for her disobedient daughter-in-law.

Once upon a time there was a girl named Psyche. She was very pretty and nice, but she was a mortal, so when Eros, the god of love, fell for her, his mother, Aphrodite, wasn't thrilled. And when your mother-in-law is a goddess, you'd better watch your step.

In order to hide his godliness from his new bride, Eros told Psyche she was never to look at him in daylight. They made love in the dark, and Eros crept away to sleep alone afterwards. Psyche's sisters thought this was strange, and they urged her to get a glimpse of her husband in case he looked like the Elephant Man or something. So one night Psyche crept into the chamber where Eros slept and held a candle close to his face. She was relieved to find that he was wonderfully handsome, but she stood gazing at him for too long, because the candle dripped hot wax on his face and woke him up.

Eros felt betrayed and walked out on his bride. Aphrodite told him it was no more than he should have expected, marrying an outsider. Psyche was devastated. She cried and mourned, realizing that she should have trusted her man, and she begged the gods to find a way to return Eros to her.

After a suitable period of self-flagellation, Psyche finally got Aphrodite to agree that Eros might come back to her—if and when she completed a few little tasks. Nothing too hard, mind you, just tokens of her good faith.

Task One: Separate the Seeds

The first task sounds easy enough. Psyche is given a bushel of seeds and told to separate them into poppy seeds, sesame seeds, etc. However, not only is the task difficult, but in addition, she is given an impossible time limit because the seeds are so many and so tiny. But Psyche gets help from an army of ants, who quickly divide the seeds into different piles.

The lessons of this task: the art of fine distinctions, of separating seeds, is a metaphor for being able to tell truth from lies, false friends from true. The ants are symbolic, too. Small helpers, people or things that seem insignificant and powerless, can become the best friends a suspense hero ever had.

Task Two: The Golden Fleece

"Get me some golden fleece from the golden rams," orders Aphrodite. This is a task that daunted Jason, and he had boats and men at his command. How is one woman supposed to face charging rams and get their fleece?

Answer: by thinking like a woman instead of a man. Psyche comes to see that she doesn't have to confront the rams to get their fleece. What she needs to do is put them to sleep with beautiful music and then creep into the field and take the fleece while they're unaware of her.

When I say "think like a woman," I don't mean that it's impossible for a female hero to pick up the sword and face danger head-on, only that if you don't

have

to face it head-on, what's wrong with an alternate approach that still gets you what you want? Psyche fulfills the task through intelligence instead of brute force; music soothes the savage beasts and allows her to take what she wants without shedding any blood, human or animal.

Similarly, the suspense hero learns to get information in ways other than simply pulling a gun on someone. Subtlety and intelligence prove mightier weapons than brute force and direct confrontation.

Task Three: Go to Hell

Aphrodite saves the best for last. Having watched her daughter-in-law separate the seeds and obtain the golden fleece, she now sets a task she's certain Psyche can't do. She orders Psyche to go into the dark realm ruled by Hades in order to get her some makeup used by Hades's wife, Persephone.

There are a few rules about going into the ancient Greek version of hell.