I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend (16 page)

Read I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend Online

Authors: Cora Harrison

‘Men fall at her feet all over Europe,’ Jane said with an air that impressed me very much, but then she spoiled it by adding, ‘even my father,’ and that made us both giggle.

We both pinned our wrappers to the shoulders of our gowns and stuck a couple of new quills in our hair. Then we tried sweeping up and down the bedroom saying, ‘la’ and ‘

chérie

’ to each other. We both decided that a train certainly made you feel much more elegant — especially as we had to keep our noses in the air in order to prevent the quills falling out of our hair.

And then Jane whispered to me that she had seen Eliza kissing Henry — on the lips too! And that the kiss lasted for ages!

I thought of how I would feel if Henry kissed me like that; I felt quite jealous of Eliza but I didn’t want to show it, so when I saw Jane looking at me I said that Eliza had a way of pursing up her lips and perhaps that was what made Henry do it, and Jane nodded wisely. ‘That’s the secret of sophistication,’ she said. ‘You must always look as if you are ready to kiss a man once you are alone.’

‘What about a girl’s reputation though?’

‘Perhaps it’s better to get married first,’ said Jane thoughtfully. ‘If you were a sophisticated widow with plenty of money left you by your husband, then you could do what you wanted.’

Monday afternoon, 14 March 1791

Mrs Austen was in very good humour this afternoon. About twelve o’clock, when I began my usual chore of dusting and polishing the sideboard, rubbing up the brass handles on the many drawers and trying to work around the books and papers and cricket balls and spinning tops and an old doll belonging to either Jane or Cassandra and all the other items that littered the shelves and cubbyholes of that huge piece of wall furniture, she stopped me.

‘Never mind about that now, dear,’ she said. ‘Jane, leave the kettle — it can do without a polish for once. Go upstairs and put on your bonnets and cloaks, the two of you; we’re going shopping at Overton.’

‘We’re getting new gowns!’ exclaimed Jane.

Mrs Austen nodded. ‘Make haste,’ she said. ‘We should go in the next few minutes. Where is Cassandra? We’ll miss the coach. I declare she takes longer over those hens every day.’

‘Here I am, Mama.’ Cassandra came in with pink cheeks and the three of us went clattering upstairs to get ready.

‘Such excitement!’ exclaimed Eliza, coming out of her room and smiling with amusement. ‘Ah, at your age there is nothing so exciting as a new gown!’

‘Are you coming, Eliza?’ asked Jane.

‘

Chérie

, I would love to, but I am only here for a

few days and I feel that I owe it to your brother to give all of my energies to the play.’

‘She’s a great performer,’ said Jane, grinning as I closed the door of our bedroom behind us. ‘She sounds just like a classical actress wedded to her art. I bet she just wants to flirt with Henry.’

‘Or James,’ I said.

‘Or both,’ said Jane. And we giggled, but I kept thinking that I hoped Eliza would flirt with James, not Henry.

Overton is a small town compared with Bristol, but still it holds all the shops necessary to the people who live in the countryside around. There are five grocers, two butchers, four tailors, seven shoemakers, one hairdresser, two breeches makers, a clockmaker and two millinery and haberdashery shops. As soon as we had got down from the coach and Mrs Austen had expressed a hope to the coachman that there would be clean, dry straw for our feet to rest on when we returned, we went straight to Ford’s, the biggest shop in the town.

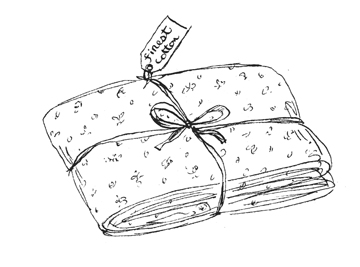

‘You’ve come just at the right moment, ma’am,’ said Mrs Ford when Mrs Austen explained our errand. ‘I’ve just got the prettiest selection of muslins, new in from Bristol.’ She bustled off and was back in a moment with

her arms laden with a rainbow of stuff, all lovely pale colours: lavenders, yellows, pinks, blues and delicate greens.

‘I was thinking of pink for all three,’ said Mrs Austen bluntly. ‘It would save money.’

Cassandra made a face, and I took my eyes reluctantly from a sky blue. I love blue, and my mother always told me it suited me best of all.

‘Why do Jane and Jenny have to have pink?’ Cassandra sounded quite upset. ‘If we are all dressed the same, it will make me look about fifteen. You know pink suits me best, but I don’t want us to look like triplets.’ She picked up a pink and gazed at it longingly.

‘That’s a lovely colour, Miss Austen,’ said Mrs Ford. ‘That’s a true shell pink. It will go very well with your complexion and your grey eyes.’ She took her eyes from Cassandra and glanced from Jane with her dark hair and her dark eyes to me with my blonde curls and blue eyes.

‘This would look good on Miss Jane,’ she said, picking up a primrose-yellow muslin and holding it against Jane, turning her around to see her reflection in the large cheval looking glass that stood on the floor next to the counter.

‘I like that much better than the pink,’ said Jane with conviction. ‘I’m sick of pink.’

‘Well, don’t have a new gown then,’ said Mrs Austen drily. ‘Wear your old one.’

‘How can I?’ Jane clasped her hands dramatically. ‘Dearest Mama, you know that I look like a half-grown pullet in that.’

I could see that Mrs Ford was trying hard to keep a smile off her face, and one of the young assistants in the background was giggling. I kept my lips tightly pressed together and did my best not to smile at the thought of Jane like one of those lanky half-grown chickens that struts around the farmyard with its long legs and small body.

‘Well, we’ll take seven yards of that pink,’ said Mrs Austen, ‘but, Jane and Jenny, you’ll have to agree on a colour.’

I immediately said that I didn’t mind the yellow, though my eyes were still on that lovely blue. It was like the sky on a fine winter’s day.

Mrs Ford held up the yellow doubtfully against me and then shook her head. ‘Not her colour,’ she said decisively. ‘That makes her look far too pale.’

‘Well, let’s have blue for the two of them,’ said Mrs Austen. ‘You don’t mind, Jane, do you?’

Jane shook her head, but she still looked longingly at the primrose-coloured muslin. Mrs Ford did not bother holding up the blue against her. Anyone could see that it wasn’t her colour.

‘It’s a pity they are not more alike in colouring, ma’am,’ she said to Mrs Austen. ‘You’re right, of course. If you can get something to suit both, you’ll save at least a yard on the making up. Wait

a moment — I’ve got an idea. Where did I put those sprigged muslins?’

‘They’re in the back room, under the tamboured muslins, Mrs Ford,’ called one of the girls, going after the flying figure of her employer.

Mrs Ford didn’t run back though. She walked slowly and carefully, bearing a brown-paper parcel reverently in her arms.

‘There you are, Mrs Austen, ma’am. This came from London yesterday.’ Slowly and gently she stripped off the folds of brown paper.

And there on the counter was lying the most lovely stuff for a gown that I had ever seen in all my life. The cloth was so beautiful, of the finest cotton, and woven so softly, that it looked just like Indian muslin. It was whiter than any snow could be and the tiny sprigs were not of a colour but were silver. Mrs Ford picked it up, and as she moved it on to her arm the light from the oil lamp caught it and made it sparkle.

‘It’s just like frost on snow,’ I said eventually, and Mrs Austen gave me a pleased grin.

‘See how it will suit both of them, ma’am.’ Mrs Ford held it up to Jane. ‘Look, it makes the dark hair and eyes look even darker, and isn’t it lovely with those rosy cheeks?’

And then she held it against me and I looked at myself in the mirror and all the young lady assistants crowded around smiling and whispering praise. I looked at myself and felt that I looked like something from the land of dreams. Only a princess could have a gown as beautiful as this one.

‘We’ll take twelve yards,’ said Mrs Austen decidedly.

After dinner, Jane and I slipped out down to the village. Jane had managed to put a basket under her shawl and in the basket she had a nice ripe apple from the orchard at Steventon. I had done a drawing of an apple and I had written the letter A beside it. I had also copied the finger shape of the sign language from Mr Austen’s book.

George was pleased to see us. He snatched the apple from Jane immediately and started to eat it in huge chunks. I was quite shocked — I didn’t expect him to have good table manners, but it seemed almost as if he were starving. He even ate the core of the apple and the little stalk on the top.

Then we showed the picture and the sign for apple, but it wasn’t a success. He just kept poking in Jane’s basket to see whether she had another one hidden there.

‘Tomorrow we’ll just show him the apple and then we’ll keep it until he makes the sign,’ I said to Jane as we walked back from the village. ‘He’ll soon get the idea.’

* * *

It was so funny today when we were passing the shrubbery — we were walking on the gravel sweep and we were not talking; I think we were both thinking about George — when we suddenly heard a sound — someone saying, ‘Shh!’ very quietly. Jane looked at me with a grin and put her finger to her lips. We both walked on until we came to a laurel bush, and then Jane ducked behind the large green leaves and I followed her. We stood there very silently for a moment.

‘They’re gone.’ It was Cassandra’s voice.

Jane put her finger to her lips again and began to steal deeper into the shrubbery. I followed her, trying not to laugh. We passed a few more evergreen bushes and then stopped. In the centre of the clearing was a huge rhododendron bush. It was a very old one and the branches with their peeling bark splayed out sideways, just a couple of feet above the ground. The bush was covered with small fat flower buds, their tips just showing purple, but deep within the leaves was a flash of pink. Hardly daring to breathe, we came a little closer and there, right in the centre, were Tom Fowle and Cassandra. They had made a little nest with heaps of old sacks and a couple of cushions. They were just lying there, not kissing, not touching, just lying there side by side looking at each other. I tapped Jane on the shoulder and turned and started to go back. Somehow

I couldn’t bear to disturb them. They looked so in love with each other.

‘Don’t tell,’ I said to Jane when we were going in through the door.

‘Of course I won’t.’

But during supper, once Mrs Austen had gone out, Jane couldn’t resist saying to her father, ‘Papa, Jenny and I have been thinking about doing some nature study — perhaps starting off with trees and bushes. Do you think that is a good idea?’

Mr Austen, of course, did, and went into a long explanation about deciduous trees and evergreens — he recommended books and he even told us we would find some excellent examples of evergreens in the shrubbery.

Jane nodded thoughtfully and said, ‘That’s just what I was thinking myself today. Like rhododendrons, for instance.’

It was good luck that Mrs Austen was out of the room because Tom Fowle went bright red and Cassandra blushed a rosy pink. It was funny, because she kept trying to shoot Jane angry glances, but then she would look at Tom and her face would get all soft again. I’m beginning to like Cassandra. I hope things work out for her.