I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend (17 page)

Read I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend Online

Authors: Cora Harrison

Tonight Jane was busy with her notebook while I was doing my journal. I had just finished writing all of this when she said, ‘Look at this. You can stick it in your journal. I might use it in a story some time.’

Mrs George Austen

The Parsonage

,

Steventon

.

Dear Madam

,

We are married and gone

.

Tom and Cassandra Fowle

.

Her Highness Madam Austen, having read this letter which, of course, sufficiently explained the whole affair, flew into a violent Passion and having spent an agreeable half an hour calling them all the shocking Names her rage could suggest to her, sent after them 300 men with orders not to return without their bodies whether dead or alive, intending that if they should be brought in the latter condition, to have them put to death in some torture-like manner, after a few years’ confinement

.

Tuesday, 15 March 1791

We had just finished breakfast and Jane and I were airing our bedroom when the dressmaker, or mantua maker, as Cassandra grandly called her, came around. We saw her on the sweep when we looked out of our bedroom window. She was a small woman with a pale face and rounded shoulders and she was carrying a flat basket in her hand.

Jane and I were downstairs before she reached the front door.

‘Miss Jane Austen,’ she said, dropping a curtsy. ‘Miss Cooper,’ she said to me, and then as Cassandra came out of the dining room, she dropped another curtsy and murmured, ‘Miss Austen.’

‘Come in, Mrs Tuckley, come into the best parlour. Mrs Austen is there.’ Cassandra was very grand today. I don’t think that she has quite forgiven Jane and me for spying on her and Tom Fowle in the rhododendrons yesterday — she wouldn’t speak to us for the rest of the day.

‘She should thank us,’ Jane had said this morning when we were brushing our hair. ‘If we don’t tease them, he might never declare his intentions to Papa.’ She lowered her voice and hissed, ‘He might abduct her by midnight in a post-coach and then she would be ruined.’

The idea of decent, kind, shy Tom Fowle abducting

the very virtuous Cassandra had made us both laugh so much that Mrs Austen tapped on the ceiling of the parlour below and told us to hurry down.

‘I’ve just brought some patterns today, ma’am,’ said Mrs Tuckley. ‘I thought that the young ladies could choose the styles that they like and then I could make sure that you had enough material and I could start work first thing tomorrow. I should have the gowns ready for a week on Saturday with no trouble, because my niece is coming to help me tomorrow and she is a good, fast worker.’

‘The young ladies can do their share also,’ said Mrs Austen firmly.

Jane made a face, probably only because she is in the middle of her novel

Love & Freindship

(as she spells it). Jane is very accomplished with her needle, better than I am.

‘Let’s see the patterns,’ she said, lifting the cover off the basket.

‘Jane!’ reproved Mrs Austen.

‘We have seven yards of pink muslin for me and twelve yards of white muslin for the two young girls to share between them,’ said Cassandra to Mrs Tuckley in a very matronly manner.

‘Two young girls and one elderly one,’ whispered Jane to me, and we

both had a giggle at that. I stopped first because I feared it wasn’t very polite to Mrs Austen when she was going to such a lot of trouble for us.

‘These are the paper patterns that I made from the Misses Biggs’ new gowns,’ said Mrs Tuckley, bringing out some large shapes of brown paper from her basket. ‘These ones are from Miss Bigg’s gown, these are from Miss Elizabeth’s gown and these from Miss Alethea’s gown.’ While she was talking to us she was able to sort out the patterns in a moment although they all looked the same to me.

Cassandra didn’t look too pleased at that. ‘Catherine Bigg will be at the Assembly Hall’s ball at Basingstoke; I don’t want to look the same as her.’ I could see that Mrs Tuckley was looking a bit worried so I picked out some black silk ribbon from her basket.

‘If this was to be plaited across the top of the bosom it would look very unusual and different and it would go well with the pink,’ I said, and Cassandra even smiled at me.

‘You are very artistic, Jenny,’ she said approvingly.

Mrs Tuckley looked relieved. ‘I’ll slot it in and out of the muslin, Miss Austen.’

Cassandra nodded graciously. She liked the very polite way that Mrs Tuckley talked to her and the way that Mrs Tuckley was always so careful to give her, as eldest girl in the family, the title of Miss Austen while Jane was just Miss Jane. Cassandra will

probably make a very good mistress of a house when she and Tom Fowle get married.

‘Here’s Elizabeth’s pattern for you, Jenny — she’s about your size.’

As soon as Jane handed it to me, I couldn’t help giving a cry of delight. ‘Oh, it’s got a train on it!’

‘They’ve all got trains.’ Mrs Tuckley was looking at Mrs Austen a bit nervously. Mrs Austen had pursed her lips and was looking disapproving. ‘Don’t worry about that, ma’am. The young ladies will be able to help each other to pin them up before they start dancing so the material won’t get spoiled.’ She was talking very quickly now. No doubt she was anxious to use these patterns, as they would save her quite some work. I was anxious too. I had never had a gown with a train before, but I could just imagine how fine I would look as it flowed behind me when I walked down the long passageway at the Assembly Rooms that Jane had told me about. Perhaps Henry would hand me out of the coach, which was to be hired for the evening, and we would walk in together, the tips of my fingers just resting on his arm, perhaps with a blue ribbon holding back my curls — if I can get my hair to stay in curl — and the train whispering along the ground behind me.

Now I must write about George. Today was a success. We fed him the apple slice by slice, and each time we made him make the sign with his fingers. In

the beginning we had to position his fingers, but once he got the idea that he would only get the apple if he made the sign, he did it himself. Bet came along while we were teaching him and she asked what we were doing. Jane told her that we were teaching George to read and she just laughed and went away.

I said to Jane that I thought Bet was unkind, but Jane shook her head and told me that Bet could not read herself and probably thought it was a very hard thing to do.

‘She’s just jealous perhaps,’ I said when we were walking home, but Jane wouldn’t agree. That’s the nice thing about Jane. Once she gives her friendship she won’t let anyone say a word against a friend, and Bet was a friend of hers.

‘Bet and I were brought up together until I was three years old,’ she said. ‘She’s my foster-sister.’

I was amazed at that and she nodded. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘My mother left us all down in the village until we could walk and talk and dress and feed ourselves. She only took us back when we wouldn’t be a nuisance to her.’

She didn’t say anything for a while. Then she added, very sadly, ‘And George never learned to do anything, so he was just left down in the village.’

Wednesday, 16 March 1791

‘Jenny, this is something that I’ve had for you for a long time. I took them from your poor mother’s jewellery box before

Madam

(Mrs Austen always called Augusta

Madam)

could take them for herself.’ As usual, Mrs Austen was in a rush. She took a box from her reticule, handed it to me, put down her teacup, finished her pound cake in two bites, pushed open the breakfast-room door and in a moment was outside shouting orders to the gardener to be sure to get more potatoes planted today than he managed to do yesterday.

The breakfast room was very quiet after she left, Mr Austen sipping his tea and reading a poem by Cowper, Henry frowning over a piece of paper from his pocket with some figures on it and Jane scribbling in her notebook. Cassandra had gone to feed the hens and all of the other boys had gone into the schoolroom. Cousin Eliza was having breakfast in bed as she did most mornings.

I opened the box very slowly. It was a beautiful box, made of thin sandalwood covered in blue silk. I had often admired it on my mother’s dressing table.

But I had never seen it opened before. It had always stayed locked.

The box was full of pale blue glass beads. They glistened in the

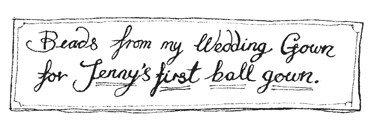

light of the pale winter sun that came through the breakfast-room window. I couldn’t stop myself giving a cry of delight. Everyone looked at me with surprise. There was a piece of paper on the top of the box with the words ‘Beads from my wedding gown for Jenny’s first ball gown’ written on it. I’ve stuck it in here as I don’t ever want to lose it.

I felt very sad for a moment after I put the note down; no doubt my mother had kept these glass beads from her wedding gown in memory of my father.

‘What’s the matter, Jenny?’ asked Jane.

I couldn’t speak, but I handed her the piece of yellowed paper. She glanced at it quickly and Henry looked over her shoulder.

‘What colour is your gown, Jenny?’ Henry put away his figures and looked at me kindly.

I told him about the white sprigged muslin, almost whispering the words because I was just thinking how beautiful the gown would look if the beads were sewn all over it. I would have to talk to Mrs Tuckley about it.