Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (12 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

Clearly, a strong affinity obtains between the contemporary study of ideologies and conceptual history. Variability, conflict, context, and the existence of fields of meaning are features held in common. Conceptual historians, obviously, concentrate on change over time. In particular, Koselleck has proposed the idea of shifting horizons of meaning. The meanings of concepts depend on the fusion of past and present horizons, or perspectives. For example, the persistent reference of 19th-century liberal ideologists to past Greek ideals of democracy infused 19th-century views with notions of the nobility of democracy and free speech. In parallel the 19th-century suspicion of the quality of rule that could emanate from the uneducated masses caused its intellectuals to superimpose a representative democracy on the direct democracy inherited from Greece. The representative model, however, was heavily qualified by restricting the vote to those who had an economic stake in the system, and by preferring the governing class to be trained in certain skills. The future is also subject to the projection of expectations nourished in past and present experience. Collective memory is both accumulative and serves as the basis from which to launch future visions. Thus celebrations of the millennium were shaped by past Christian religious experience and by an inherited method of time-keeping that endows round numbers with ceremonial significance. But it was also a statement

of expectations of a new beginning, grounded on 19th- and 20th-century hopes for infinitely self-propelling social and technological progress.

Conceptual historians are less fastidious about the sources they use than are philosophers. The classical texts beloved by political philosophers are only one of their concerns, and they are quite happy to peruse newspapers, pamphlets, speeches, party manifestos, and official publications. This move away from elitist articulations is close to the heart of students of ideologies, who share with conceptual historians the common purpose of comprehending ordinary political speech and thought. This quest for the commonplace and the widespread indicates the important step of normalizing ideologies instead of pathologizing them. It brings ideologies into the ambit of the phenomena one would expect to explore when conducting standard political research.

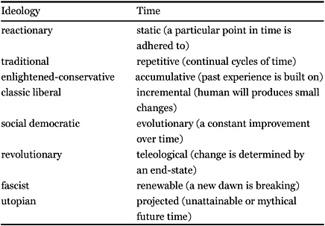

Conceptual historians have reminded us that time is a crucial dimension for studying concepts (and by extension ideologies). Historians of ideas have done this for a while, but one weakness of their past approach has been to abstract the history of a concept from its context. The history of freedom has all too frequently been presented as if one could trace its evolving meanings from ancient times to the present and rest content with that. The historian Quentin Skinner and others have corrected that view through directing historical research towards the intentions of actors and authors, for which an appreciation of the contexts and discontinuities of ideas is essential. When applied to ideologies, time becomes an interactive factor not only in locating but in constituting them. Time, we now know, is not the remorseless ticking of clocks, but can be bent to the human will and subjected to the human imagination. Various conceptions of time animate different ideological tendencies, as the list illustrates in rough terms.

Social and historical time does rely on some indisputable facts, but one central feature of ideologies is to link both diachronic and synchronic facts selectively in a web of resourceful imagination. The disjointed becomes joined up; the random becomes open-ended and progressive, or closed and oppressive. Conceptual history and the study of ideologies are cognizant of human agency in choosing our futures, but they are aware of the manifold constraints within which such choices operate. One dictum of Marx’s has re-acquired a resonance that analysts of ideology would do well to heed:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past.

Past packaging limits analysts of ideology in interesting ways, and they have to toe a fine line. The notion of family resemblances enables scholars, as we saw above, to refer to a plethora of socialisms held together by this Wittgensteinian device. Because the monolithic view of ideology at the centre of the Marxist approach

was challenged by the indeterminate meanings ideologies could carry, a richer and more pluralistic view of their internal variations emerged. On the other hand, we have already stressed that ideologies differed from the more open texts discussed by hermeneutic scholars

because

of their historical formation, and

because

they constituted political traditions. Those traditions constrained the prospect of an infinite number of liberalisms knocking on the door of the family home and claiming membership. Ultimately, the study of ideologies must be grounded on empirical data, because it concerns actual manifestations of collective political thinking.

How do we decide that a particular set of beliefs is part of ideology A rather than ideology B? This calls for a balance between self-definition (liberals are all those who proclaim themselves liberals) and other-definition (liberals are those who some external authority – say, a scholar of liberalism or a politician – declares to be liberal according to some well-defined criteria). Adolf Hitler’s claim to be a national socialist then poses a classificatory problem. Is Nazism merely a version of socialism with a nationalist twist? Here self-definition may not be enough. But, rather than simply assert that it isn’t socialism, we require an empirical test of self-definitions. We might read, say, a hundred texts that claim to be on socialism. Some family features will then emerge from our readings, and on their basis we can decide whether national socialism resembles those features sufficiently for it to be deemed a member of the socialist family, or whether the name is (deliberately) misleading and Nazism is really a very different kind of ideological animal. Those texts – as conceptual historians recognise – constitute a past field of mutually reinforcing meanings from which we cannot completely escape.

Labeling an ideology ‘socialism’ itself moulds an identity that constrains the future movement of the encompassed concepts, and acts in the political world as consciousness-shaper and a regulator of political conduct. ‘Socialism’ becomes an idea-entity that

occupies some of the essential space available for the expression of political ideas. ‘Socialism stands for …’ is a common mode of bestowing the illusion of autonomous life on these specific, contingent, yet aspirationally durable, constructs and traditions. The weaving of that imaginative coherence is a major component in parcelling out the realm of the political. Among themselves, the major ideological families both channel the ways in which those ideas are legitimated, understood, and taken seriously, and crowd out other ways of enunciating effective political thought. Access to the meanings of political concepts is then mediated, and significantly rationed, by having to use the gateways provided by extant ideological families – a practice cemented by a tacit appeal to these labelling conventions.

The clash of the Titans: the macro-ideologies

We leave for a while the various ways of analysing ideologies and move to survey the forms that political ideologies have adopted. Throughout much of the 20th century the prevailing ideologies have been overarching, inclusive networks of ideas that have offered solutions, deliberately or by default, to all the important political issues confronting a society. Those macro-ideologies have sought social and political acclaim and dominance on both national and international levels. In recognizing their centrality we are deferring to the power of tradition and convention as classifiers of ideologies, not forgetting that other classifications could be retrospectively possible. Liberalism, conservatism, socialism, fascism, communism, and other major families, have been virtually reified as political actors in their own right. Indeed, much of the past century can be viewed as a generally vitriolic, and frequently bloody, battleground among them. Far from being marginal epiphenomena, ideologies have shaped the political experience of the modern world.

Most modern ideologies have adopted an institutional garb, in the form of a political movement or party. This is hardly surprising if we recall that ideologies are competitions over providing plans for public policy. Yet it would still be a mistake to assume that conservatism or liberalism are absolutely identical to what Conservative or Liberal parties stand for. Ideologies are rarely

formulated by political parties. The function of parties in relation to ideologies is to present them in immediately consumable form and to disseminate them with optimal efficiency. Parties operate at the mass production end of the long ideological production line. Ideologies

emerge

among groups within a party or outside of it. Those groups may consist of intellectuals or skilled rhetoricians, who themselves are frequently articulating more popular or inchoate beliefs or, conversely, watering down complex philosophical positions.

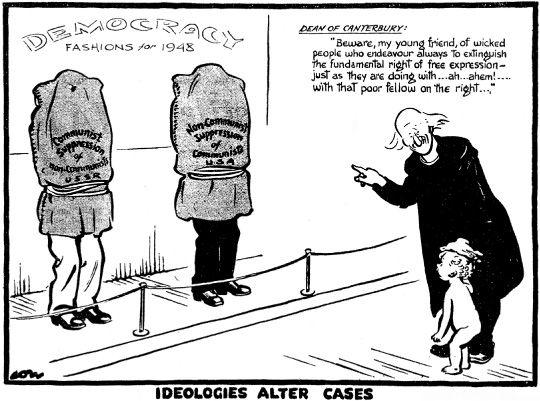

It is common to describe ideologies as ranging from the left to the right in a continuum of beliefs from communism, through socialism, liberalism, and conservatism, to fascism. Recently, attempts have been made to challenge this ordering. Green political thinkers have famously described themselves as neither left nor right, but in front; some versions of fascism have also, but more dubiously, claimed to be neither left nor right; and the 1990s obsession with ‘third ways’ has proffered a synthesis of a dialectic view of ideological politics. The advantage of these classifications is that an attractive clarity descends on the marketplace of political ideas – a very useful illusion when mustering support. The left-right continuum, however, is itself largely ideological. It serves the purpose of bestowing a moderate or, respectively, radical or even dangerous aura on an ideology; it suggests that to move among ideologies can be a gradual process; and it indicates that ideologies are mutually exclusive and hence offer clear-cut alternative choices.

10. Ideologies alter cases

.

None of these implications is correct, but we need both micro- and macro-analysis in order to remedy them. The micro-analysis is provided by the morphological approach to ideologies that offers a way of assembling them and exploring their inter- and intra-relationships. The macro-analysis is provided by looking at ideologies as traditions over time and space, whose imagined aspects themselves become part of political reality. The two approaches are complementary: they offer alternative access to

studying the same thing. Beginning with the conceptual structure, we may apply the notions of decontestation, family resemblances, core, adjacent, and peripheral concepts, and permeable boundaries to some of the main ideological groupings. Most modern ideologies are complex. They cannot be summarized in oversimplified generalizations such as: liberalism is about liberty; conservatism is about preserving the status quo; and so on. They all exhibit a cluster of core concepts, none of which can be maximized without some damage to the others, and consequently to the ideological profile as a whole. As noted above, the proportionality principle teaches us that, if one concept expands to fill up all available space, it will end by crushing the others or subsuming them within its domain.

Liberalism consists of several core concepts, all of which are indispensable to its current manifestations. The supposition that human beings are

rational

; an insistence on

liberty

of thought and, within some limits, of action; a belief in human and social

progress

; the assumption that the

individual

is the prime social unit and a unique choice maker; the postulation of

sociability

and human benevolence as normal; an appeal to the

general interest

rather than to particular loyalties; and

reservations about power

unless it is constrained and made accountable – all these are the minimum liberal kit. Superimposed on that kit is a crucial disposition: a

critical questioning

of motives and actions that introduces a readiness to rethink one’s own conceptual arrangements and practices, and to tolerate those of others.