Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (7 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

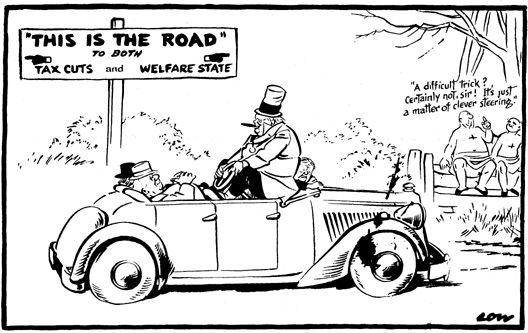

7. This is the Road

.

The climax of this popular rejection of ideology was spearheaded by the attempt of several reputable scholars to declare the end of ideology in the 1950s and 1960s. This stark rejection of ideology was the product both of the historical interpretation adopted by these scholars – and their mimics in the mass media – and of the espousal of an even more restrictive theory of ideology than the one that had emerged from Marxism. They believed that the defeat of the totalitarian regimes signalled the demise of brutal strife for world ideological domination. Rather, both Russians and Americans sought a consumer-oriented society and aspired to similar creature comforts. The result would be a convergence between previously hostile world-views, dictated by the necessities of good living. This view appeared plausible at the time. After the

ideological ‘over-heating’ of the 1930s and 1940s, the 1950s seemed particularly sterile. Western societies were emerging from a devastating war, while the granting of independence for European colonies was only beginning. Economic stability by means of a mixed economy was a major political goal. On the positive side, great strides had been made in establishing welfare states in Europe but, in ideological terms, this created the impression of consensus politics and the termination of divergence over principles.

The end-of-ideology theorists were taken in by a series of delusions. The first was a logical error. If conservatives, liberals, and socialists all agreed on implementing the principles of the welfare state – namely, a state supported redistribution of social goods and the underpinning of human flourishing as a central political aim – this did not imply the end of ideology but the confluence of many ideological positions on a single point. There could still be a (more or less) common ideology of the welfare state. The second was a faulty historical prediction. The 1960s were about to witness an explosion of new ideological variants, particularly in the Third World. African socialisms, Indonesian guided democracy, pan-Arabism, all these now entered the political arena, demonstrating the ingenuity of the human mind in devising new forms of sociopolitical thought.

The third was an analytical mistake. Ideologies do not only diverge over grand principles but also over peripheral and detailed practices. Even were we to assume complete agreement on the principles of the welfare state, ideological dissent could simply be deflected to what may seem to be technical questions: (

a

) how do we raise the money for welfare services? (

b

) which groups should receive priority in obtaining state help, given that budgets are always limited? These questions, however, clearly elicit a plethora of different ideological solutions. Direct taxation or indirect taxation involve divergent principles. The former may be graduated, making the rich pay proportionately more. The latter could impose a similar tax on rich and poor, thus becoming a regressive rather than a

progressive tax. Who should get help first is a question of sorting out priorities: do the young have precedence over the very old? The unemployed over the sick? The physically disabled over the mentally disabled? Single mothers over asylum seekers? These all are major ideological distinctions that reflect very different understandings of the values involved in policy-making.

In response to question

(a)

, assuming that welfare states promote some form of equality, equality emerges as the proportional ability to bear a financial burden; and the advocacy of redistribution from rich to poor, given an original unfair distribution. Here is one set of issues that centrally concerns all ideologies: which pattern to adopt in distributing scarce social goods? In response to question

(b)

we have a competition among needy groups, all with legitimate claims for assistance in coping with life circumstances over which they have very limited control. This set of issues, too, centrally concerns all ideologies: how to prioritize competing claims from deserving or vulnerable groups while maintaining the vital political support without which an ideology may flounder.

The ‘end of ideology’ was in several ways also a retrogressive

theoretical

stance. It reverted to endowing ideology with an aura of apocalyptic thinking, the unfolding of an historical truth with scientific pretensions, a method of social engineering, and the passion of a secular religion. It picked up the thread that saw ideology as the creation of intellectuals as ‘priests’, derogatorily depicted as distanced from society and pursuing ‘pure’ thought. For one of its main detractors, Daniel Bell, ideology was an ‘irretrievably fallen word’; for another, Edward Shils, ideologies were always alienated from their societies and always demanded individual subservience to them. The Marxist conception had apparently brought Western theories of ideology to a dead end. That overlooked the subtle insights that Mannheim, Gramsci, and Althusser had in their different ways enabled the concept of ideology to acquire; indeed, it overlooked the subtleties that Marx himself had developed on the topic. Contra the ‘end of ideology’

advocates, the usefulness of the

notion

of ideology – let alone the actual systems of ideas signified by that notion – was still clearly evident. While some avenues appeared to close, others were opening up.

The development of the social sciences in the United States brought in its wake a non-Marxist view of ideology, removed from the theoretical concerns that preoccupied European scholars. The empirical bent of political science focused on field research, on the attitudes and opinions of the new mass publics that were attracting the increasing attention of the discipline. That process was further fuelled by the extolling of democratic politics and the ‘common man’, in part as an antidote to the dictatorial and elitist voices of the 1930s. Ideologies were now tantamount to political belief systems, and the task of the researcher was to describe them and to place them in categories that could be ‘scientifically’ generalized and, more often than not, measured. Statistical methods came into their own in exploring the distribution of beliefs, their aggregation, and variation. One could combine individual opinions – dispersed across a given population – into groupings that shared common experiences.

In this milieu ideologies were taken as explicitly known to their bearers – or, in psychological language, cognitive. The technique was known as behaviourist, that is, focusing on concrete and observable forms of human conduct, not on broader social forces or unconsciously held worldviews. Ideologies were, moreover, assumed to contain not only factual information about a political system but moral beliefs about human beings and their relation to society. Those were thought to hold the key to human action or inaction. Notwithstanding, that methodology was far more indebted to the sociology of the day than to philosophy. Furthermore, these belief systems were acknowledged to be ‘emotionally charged’ rationalizations and justifications, in the

words of one of the key writers on this approach to ideology, Robert E. Lane. In sum, ideologies were there to be discovered by the keen social scientist.

Notably lacking was any sense of grand political and ideational schemes – after all, the role of American political parties did not include the disseminating of the great ideological traditions, as did their European counterparts. Instead, ideologies were thought to be rather unstructured and lacking analytical depth. We all held them as part of our psychological and mental equipment. Their study could enable scholars (and politicians) to take the attitudinal pulse of their societies and to draw their own conclusions. Left-right continuums, mimicking the seating arrangements made famous during the French Revolution, could be employed to gauge opinion on war and peace, social services, or political reform. Two-by-two boxes could help distinguish between authoritarian and democratic personalities married to either rational or irrational conduct, or correlated with a predilection for state planning versus free markets. None of these modelling devices could express the complexity of ideological structure and the interweaving of such categories. That application of the social sciences simplified life, and prevalent perceptions of ideologies were tarred with that simplicity. The potential of ideology as a pivotal organizing concept of political thought looked unpromising.

At that point succour came from outside the discipline of politics. The borrowing and exchange of explanatory paradigms among disciplines is one of the most fertile ways of developing new thinking in a given field, and they paved alternative paths forward for interpreting the nature of ideology, giving its conceptualization a much-needed boost. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote a seminal article in 1964, in which he portrayed ideologies as an ordered system of complex cultural symbols. These symbols acted as representations of reality and provided the maps without which

individuals and groups could not orientate themselves with respect to their society. If one political system had frequent recourse to marches and military parades, these served as cultural symbols of national vigour. An ideology could then prioritize power over, say, welfare. If another political system blamed foreigners or a particular ethnic group in its midst for economic and social malaise, they too served as cultural symbols of certain behavioural traits that the members of that society envied, desired, or dissociated from themselves. An ideology could then displace internal political criticism onto those ‘anti-social’ symbols.

Geertz’s contribution to the theory of ideology was to grasp that ideologies were metaphors that carried social meaning. Put differently, they were multilayered symbols of reality that brought together complex ideas. Take an ideology that, for example, advocated the importance of the ballot box. That concrete symbol could be employed as a rhetorical device locating ultimate decision-making in the people (though democratic theory may suggest otherwise). It could also be an emotional representation of why loyalty to the system should be forthcoming, and serve as an institutional deflection of political responsibility away from the leadership. The ballot box could also paper over contradictions and ambiguities. It combined the notion of devolved and accountable power with a situation of individual choice in which the voter was socially isolated from group consultation and accountable to no one. These conflicting elements of democracy were obscured through the symbolism of the ballot box.

For Geertz, the symbol-systems we call ideologies constituted maps of social reality. Maps, after all, are themselves symbols, simplifying the terrain through which they are intended to guide us. Maps are selective; they protect us from over-information that may be quite useless. If I wish to drive from London to Birmingham, I do not need to know every bump in the road, and I wouldn’t be able to handle, physically or mentally, such a detailed map. It certainly

wouldn’t fit in the car. Ideological maps, however, are special kinds of maps. They have flexible notions of proximity between the components of the ideology. They may, for example, bind the idea of legitimacy to the institution of hereditary monarchy, or align it with the directives of a sacred text, or attach it to the seal of popular consent. We may consequently conclude that ideologies are symbolic devices that order social space. They tell us what to look out for but, as we noted in

Chapter 1

, there may be competing ideological maps for the same social reality, maps that trace different routes among the social principles and practices they detect. Thus, the encouraging of liberty may lead to individual development and be valued for that reason, but it may also lead to lifestyle choices that fly against conventional morality, and hence be condemned. The one may be a liberal path that trusts individuals to make rational use of their liberty; the other a conservative path that insists on social constraints and objects to individual experimentation.

In addition, ideologies also order social and historical time. Historical time is far from being a record of everything that ‘happened’. It is a selective and patterned listing of events (some of which may even be mythical, such as the founding of Rome by Remus and Romulus) that are woven together to form an ideological narrative. English history has singled out landmarks such as the Magna Carta of 1215, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the several enfranchisement Acts between 1832 and 1918 as formative political experiences. That story – symbolizing England and later the UK as a nation with a strong heritage of liberty – is one of which UK citizens are expected to be proud, but it is only one of many stories we could tell about the history of this nation, not all of which would be flattering. A history of the role of women in the UK would produce a very different tale. In this capacity, ideologies are collections of symbolic signposts through which a collective national identity is forged.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein also contributed importantly to the study of ideology, though his contribution was indirect and unintended. Wittgenstein argued that language was akin to a game, and a central characteristic of a game is that it has rules. Using a language meant learning its rules. Rules both permit and constrain; they may be general or highly specific. From this others deduced that ideologies, too, are a form of language game, whose meaning and communicative importance can only be determined by noting their grammar (the fundamental structures and patterns of relationship among their components), their conventional employment in a social context, and the degree of acceptability of the rules by which they play. I would only subscribe to Nazi doctrines if the rules of Nazism made sense to me. They would do so if I accepted that the word ‘Aryan’ was a desirable, and the word ‘Jew’ an undesirable, term for the features of a group. Moreover, the rules of that language game pitted Aryan against Jew as opposites. By further classifying Jews as ‘subhuman’, their elimination could not, by definition, be a crime against

humanity

.