Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (5 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

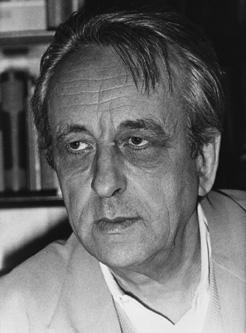

The contribution of Antonio Gramsci, the radical Italian Marxist theorist and activist (1891-1937) to the analysis of ideology is significant in ways both different from and parallel to Mannheim’s. Gramsci modified the Marxist understanding of the term working

within

a broadly Marxist tradition. He is best-known to students of ideology for his notion of hegemony. Ideological hegemony could be exercised by a dominant class, the bourgeoisie, not only through exerting state force but through various cultural means. Gramsci shifted ideology away from being solely a tool of the state. Ideology operated and was produced in civil society, the sphere of non-state individual and group activity. Here again the intellectuals surfaced as the major formulators and conductors of ideology and as nongovernmental leaders wielding cultural authority. Their permeation of social life was characteristically based on the manufacturing of consent among the population at large, so that the masses would regard their own assent as spontaneous. That process of forming consent – which Gramsci termed leadership as distinct from domination – necessarily preceded, and paved the way for, the dominance wielded through governmental power. Gramsci was therefore inclined to sharpen the distinction between ideology as a more conscious creation for its producers, and a more unconscious one for its consumers.

One perspicacious move forward of Gramsci’s in investigating ideological hegemony was his sensitivity to its importance, albeit from a Marxist perspective. The establishment of hegemony involved the coordination of different interests and their ideological expressions, so that an all-embracing group, possibly society as a whole, would be engaged. Hegemony produced compromise – an equilibrium that took some account of the subordinate groups. Marxist class confrontation gave way to the building up of solidarity in a manner that could serve the Marxist end of a unified community. That was so because different ideologies maintained a state of conflict until one of them, or a combination of some, prevailed. The result was an intellectual, moral, economic, and political unity of aims with the semblance of universality. But there was also a liberal undertone to Gramsci’s theory of ideology, which he himself did not emphasize. It was based on a voluntarism embedded in civil society that we associate – at least on the surface – with free choice, consent, and material or

intellectual markets. Another chink had been opened in the Marxist armour.

Gramsci saw the notion of hegemony as a great advance, both philosophical and political, towards a critical and unified understanding of reality. In the course of the historical process a new intellectual and moral order could evolve, an ‘autonomous and superior culture’ with ‘more refined and decisive ideological weapons’. Gramsci’s theory of hegemony attempts to raise some questions Marx had left unasked. What are the forms that ideological control takes? What is the relationship, and the difference, between ideological and political domination? Can we account for the multiplicity of ideologies, and for their rise and fall? In what sense, if any, do people

choose

to believe in an ideology? With these questions on the agenda, a range of possible answers would be provided during the remainder of the 20th century.

Gramsci’s theory of hegemony notwithstanding, his role is retrospectively more important for another aspect of analysing ideology. As against the abstract and rarefied nature of the Marxist conception of ideology, exposed as a way of concealing and inhibiting correct social practices, Gramsci sought to explore the working of ideology as a practice in the world. We might refer to ideology as a thought-practice. This simply means a recurring pattern of (political) thinking, one for which there is evidence in the concrete world. The evidence for our thinking lies in our actions and utterances. Our thought-practices intermesh with, and inform, material and observable practices and acts. Sometimes it makes more sense to trace a movement from theory to practice; at other times the theory can be extracted from the practice itself. We are always looking at a two-way street.

4. Antonio Gramsci

.

For example, a belief in free choice is a recurring pattern among liberals, applied to innumerable situations such as voting, shopping, or choosing a partner. In the case of voting it can be held as a conscious general ideological principle. Voting is a deliberate

exercise of political choice at the heart of liberal ideologies, linked to the core notion of consent. Shopping is participation in economic free-market transactions, though shoppers are rarely aware that their practice embodies the principle of free trade. Selecting a partner for emotional and sexual relationships is a conscious ideological thought-practice only when put in the context of arranged marriages. Otherwise it is an ideologically unconscious practice that has to be decoded by analysts as an embodiment of the voluntary principle. We do not choose partners just because we wish to demonstrate our adherence to the principle of free choice, but it is a largely invisible instance of such choice. The upshot of all this is to see ideologies as located in concrete activities, not as floating in a stratosphere high above them. The dichotomy between doing and thinking is challenged, for thinking is an activity that displays its own regularities. Political thinking is evident in reflection on how to organize collective behaviour, but it may also be retrieved through unpacking empirically observable acts.

Marx and Engels had dismissed German philosophy as a metaphysical form of ideology, practised by a few professionals. Gramsci sought to bring philosophy down to earth by suggesting that most people were philosophers in so far as they engaged in practical activity, activity constrained by views of the world they inhabited. At a stroke, Gramsci demystified philosophy and reintegrated it into the normal thought-processes of individuals. He did this, however, while retaining a threefold structure of political thought. There were individual philosophies generated by philosophers; broader philosophical cultures articulated by leading groups; and popular ‘religions’ or faiths. The second type was an embodiment of hegemony, and displayed the features of coherence and critique that hegemonic groups eventually imposed on the thinking under their control. The third type existed in embryonic form among the masses, for whom general conceptions of the world emerged in sudden and fragmented flashes. Importantly for Gramsci, each of these three levels could be combined in varying proportions to produce a different ideological cocktail. The

distinction between the philosophical and the ideological began to evaporate the moment political thought was situated in the concrete world and directed at it.

What do we know about ideology, with Gramsci’s help, that we might not have known before? As with Mannheim, Gramsci elevated ideology to the status of a distinct phenomenon worthy of, and open to, study. It inhabited a broad political arena that included moral and cultural norms and understandings, disseminated through the mass media and voluntary associations. And quite crucially it was to be found at various levels of articulation. True, ideology tended to a unity – central to the consensus and solidarity it forged – because the leading intellectuals of a given period subjugated other intellectuals through the attraction of their ideas, and directed the masses. These intellectuals, unlike Mannheim’s, did not dispense with ideology; their mission was to modify it in line with the needs of the time. Part of such a modification would reflect the common sense of the masses, ‘implicitly manifest in art, in law, in economic activity and in all manifestations of individual and collective life’.

Ultimately, Gramsci leaves us somewhat unsure of the nature of ideology, but he equips us with tools that enable us to proceed further. He confusingly vacillated between the Marxist view of ideology as dogma and a valiant attempt to release ideology from its negative connotations. He regarded ideology as achieving unity within a ‘social bloc’ – a cohesive social group – and held out hope for a total and homogeneous ideology that would attain social truth, while urging us to take current instances of ideology seriously. Even more than with Mannheim, a unified expression of the social world would emerge out of ideological pluralism. But Gramsci had a good grasp of the concrete and diverse forms in which ideology presented itself, in particular of its qualitatively variable voices. If Marx and Engels wished us to disregard the airy-fairy thoughts of intellectuals, and if Mannheim wished to reconstitute the intelligentsia as a source of unbiased theorizing about society,

Gramsci recognized the role of popular thinking in dialogue with the intelligentsia, producing the kind of complex ideological positions that characterize the modern world.

The place of Louis Althusser, the French Marxist philosopher and academic (1918-90), in the development of theories of ideology is somewhat less significant than Mannheim’s or Gramsci’s, although Althusser is regarded as a major redefiner of ideology within the Marxist tradition. Althusser followed Marx in assigning the ruling ideology the role of ensuring the submission of the workers to the ruling class. That was achieved by disseminating the rules of morality and respect required to uphold the established order. Official ‘apparatuses’ such as the state, the church, and the military practised control over the ‘know-how’ that was necessary to secure repression and ensure the viability of the existing economic system. But Althusser departed from Marx in acknowledging that ideology was a ‘new reality’ rather than the obscuring of reality. He likened the ideological superstructure to the top storey of a three-storied house. It was superimposed on the economic and productive base – the ground floor – and on the middle floor, the political and legal institutions. These were also part of the superstructure, but one that intervened directly in the base. Although the upper floors were held up by the base, they exercised ‘relative autonomy’.

5. Louis Althusser

.

Effectively, the repressive state apparatus was the dominating political force, but ideology developed a life of its own as the symbolic controller. The ideological state apparatuses were located in religious, legal, and cultural structures, in the mass media and the family, and especially in the educational system. One input of Althusser into changing understandings of ideology was to recognize the variety of its institutional forms – the multiplicity of ideological apparatuses as against the singularity of the illusion that Marx and Engels had decried. A second input was to acknowledge the widespread dispersal of ideology beyond the public sphere to

the private (Althusser did not distinguish between the private area of the family and the broader civil sphere). Political views of the world were present in all walks of life. But as with so many other Marxists, this was a qualified plurality: ideology was plural only in its location in diverse social spheres. It was not plural in its functions, retaining only the Marxist function of exercising unified

hegemonic power so as to maintain existing capitalist relations of exploitation. Althusser refused to be drawn into formulating a theory of particular ideologies, nor was he interested in aspects of ideology that were unrelated to oppressive power.

A third input was the insistence that ideology has fundamental features irrespective of the historical forms specific ideologies adopt. It is one with which contemporary scholars of ideology have much sympathy. Unlike Marx and Engels, Althusser declared that ‘ideology is eternal’. By that he meant that individuals inevitably think about the real conditions of their existence in a particular manner: they produce an imaginary account of how they relate to the real world. Ideology was a representation, an image, of those relations. For example, to describe certain nations as freedom-loving may allude to existing practices in their countries that suggest that individuals do not want to be ruled over arbitrarily: elections, a free press, a judiciary that can regulate the executive. But at the same time, the phrase ‘freedom-loving’ is rich with ideological import. It is an imaginary representation of a nation as a crusader for such freedoms, even when that crusade involves war and intervention in other people’s freedoms, and serves to promote the economic interests of that nation. Ideology permits societies to imagine that such actions really do further the cause of freedom. It provides a view of their real world that explains it and reconciles them to it. Ideology does that by obscuring from a society the illusory and (favoured Marxist term) distorted nature of that representation. Ideology is inevitable because our imaginations cannot avoid such distortions.