If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (15 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

Another Super-8 standby was brought up to Marshall courtesy of Scott's employment at the Walnut Lake Market: canned cherry cobbler. This provided a perfectly thick, pulpy substance for Mary Valenti to vomit out upon being stabbed in the neck.

Titanic

can have all of its fancy computer graphics, I'll take a good off-brand pie filling any day.

This shoot also required my first full-on monster makeup. During the course of the film, my character is found horribly mauled in the woods and later I appear as a possessed creature. Without the luxury of an extended shoot, our scheduling demanded for shooting horror at night and horror in the morning -- roughly translated, it meant that Bruce slept in his makeup. I was still on the waning edge of that "perceived indestructibility" teenagers are blessed with, so I didn't think much about it... at the time...

When the shoot was over, however, I realized that my skin had undergone a disturbing change -- of the DNA variety. Where the latex makeup had been applied, fascinating patterns began to emerge. Coincidentally, they were shaped exactly like my latex appliances. These rashlike apparitions remained with me for months -- a lingering reminder of blatant stupidity. I also found out, after the fact, that the stuff I was almost always drooling as a monster was actually black latex paint. Hell, who needs a functioning intestinal system, we had great-looking bile!

Within the Woods,

as well as serving as a prototype, allowed us to experiment more extensively with the concept of "fakery." It was the first time, in the interests of getting the most out of our schedule, that we blacked out windows to provide the false illusion of night. It also was one of the few times that we actually filmed outdoors at night...

all night.

Despite the newfound hardships, the film came together very well. It was our first collective effort to actively pursue a genre and it worked. Sam had clearly made strides as a filmmaker, and I began to get a basic grip on this elusive,

acting

thing. Well, okay, it wasn't acting, per se, but I had taken a baby step beyond the "mugging for the camera" phase...

Once assembled, we did our own brand of test marketing to see if

Within the Woods

would get a response from regular civilians. What could be a better proving ground than our old high school? A screening was arranged and the feedback was good... and

loud.

Hell, this film got a better response than

Six Months to Live.

We weren't experienced filmmakers by any means yet, but this audible feedback was all the encouragement we needed to take the next leap.

13

THERE'S NO BUDGET LIKE LOW-BUDGET

We had a useful prototype, but what was the next step? The

how

question still fluttered about. With Michigan, you had to plan months ahead, just to factor in the weather. Summer 1979 became the target for shooting, but we had to get our act in gear -- May flowers were already in full bloom.

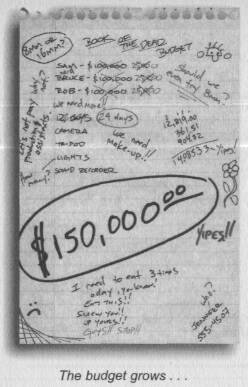

Before we attempted to raise any money, we had to figure out how much was needed. For the first time, we had to determine, in advance, what our film might cost. This was an entirely foreign concept to us, since we had always casually pooled our loose cash and shot whenever we could and with whomever was available. A "professional" endeavor like this would call for renting equipment that wasn't ours, using a real film laboratory and, yikes, even

paying

people.

In my year as a production assistant not long before this, I had become reasonably familiar with a number of motion picture suppliers in Detroit who catered to commercial producers. Technically, we were just doing a long commercial, so we gathered price lists and began to jot some numbers down.

Long before the days of budgeting software, we started with a blank sheet of paper. Not knowing any other method, we proceeded to make the film in our heads, reviewing every phase of production.

"Okay, we gotta rent equipment...

what

equipment? For how long?"

"What do you pay production assistants? Should we pay them at all?" There were the odd "how to make an independent film" guides available, so we got our hands on whatever we could at the local bookstore. Our little hand-hewn budget began to grow... and grow. Eventually, it reached an inconceivable $150,000. For all we knew about raising money, it might as well have been a million.

Being so immersed in the Super-8 format, we convinced ourselves that we could save lots of money if we shot our feature in that same format and blew it up (enlarged it) later to the industry standard of 35mm. Was this an insane idea? We had never seen a film in a theater that had originally been made in Super-8, but there was always a first time...

A company in San Francisco (Interformat Labs) could fill the obscure request. The fellow in charge, Mike Hinton, sent us a test of a film that was shot in Caracas Venezuela on Super-8mm and blown up by them to 35mm. When the test arrived, we marched down to our local Maple 3 theaters in Birmingham and screened it.

The print looked okay, but just okay. We asked the projectionist what he thought about the quality of the film. He assumed it was a blowup from 16mm, a fairly standard process. This was very encouraging to us, but we proceeded to test it for ourselves -- this turned out to be good idea.

What resulted was

Terror at LuLu's --

as in Lulu's Lingerie. Sam's mother had recently opened a string of these shops and it seemed like the perfect place to stage a

Clockwork

-like film.

We cast another aspiring actress, Liz Dennison, as an unsuspecting woman working late at night who is terrorized by a mysterious man/thing. This wasn't so much a story as a technical test, and it only took one night to put this small sequence together. We merely wanted to assemble enough shots -- light, dark and in between, to satisfy our curiosities of how each exposure would hold up in a blowup process.

On the advice of the San Francisco lab, we used a Boleau, the very best Super-8 camera we could find with a very specific film stock. We rented professional lights, for the first time, and used professional cameraman, Steve Mandell, to shoot the thing. In short, we did everything we could to make it work.

The results, once back from the lab in San Francisco, were nothing short of disastrous. Screening it again at the same local theater we stared, slack-jawed, at an image that was obscured by enormous globs of grain -- it looked like the action was taking place in a hailstorm.

This was a real blow -- our budget, meager as it was, didn't seem to support the jump to a more expensive format. On a hot, depressing day in June, the three of us sat on Rob's screened-in porch trying to make the decision to go forward or stop dead in our tracks. We reasoned that a number of the then-classic low-budget horror flicks had been shot in 16mm. By making the leap to that millimeter we were, in reality, merely making it all the more possible to pull off.

We decided, after some wailing and gnashing, to blast ahead in the format.

14

THREE SCHMOES IN SEARCH OF A CLUE

We reasoned that another impediment to raising money was credibility. Three guys with no professional experience, questionable education, and a dream to make a film in Detroit wouldn't exactly make the average investor dive into his pocketbook.

We had to shake the "flaky" image of filmmakers and conquer the Midwest, "kick-the-tires" mentality. If we were going to immerse ourselves in the world of business, we had to

look

like businessmen. Mostly, this meant that we had to dig up, dust off or just plain buy a suit.

Fortunately, a love of "cool old suits" gave me a leg up. I had already accumulated three or four vintage, double-breasted wool outfits. My basic theory had been to haunt Salvation Army stores with a methodical zeal, and soon I knew when and where to look for the good stuff. An annual church bazaar in a nearby wealthy neighborhood produced a great bounty as well -- castaways from the Detroit elite. Hell, if it was good enough for the Fords and the Fishers, it was good enough for me.

My usual layout for a primo suit was twenty-five bucks. Dump another $15-20 on top of that for tailoring, and $10 for some two-toned wing-tip shoes, and you've got yourself, on average, a $50 masterpiece. I was stylin' in the Motor City.

We also needed briefcases, so it was off to Montgomery Ward. I opted for the "double wide," while Rob and Sam took the sleek "slim line" models.

Aside from all the trimmings, we needed confirmation that we were for real. Of course,

we

felt qualified, but a second opinion from someone actually in the film business who could bless us from on high seemed like a useful thing.

The only professional person we knew, a family friend of the Taperts, was a film exhibitor at Butterfield theaters in Detroit. We set up an appointment at Andy Grainger's downtown offices.

Walking into his lobby was like stepping into a time warp. His receptionist still used the forties-style plug-and-patch phone system and the walls were adorned in a rich wood paneling. Appropriately, I was wearing one of my aforementioned vintage suits.

Andy's advice was simple: "Fellas, no matter what you do, keep the blood running down the screen." As a tribute to him specifically, there is a scene in the finished film where an old film projector whirs to life and "projects" blood running down the screen.

Most importantly, Mr. Grainger provided the name of a distributor in New York City whom we could approach for possible distribution -- Levitt-Pickman films. Their claim to fame had been

Groove Tube,

featuring a very young Chevy Chase.

Little did we know that a letter of "intent" was all one could really expect without a finished film, but that was good enough for us and we set up an appointment to meet with them. I'm not sure what dream world we lived in, but we were convinced that the only way to get to New York was by train.

Bruce: Wasn't that kind of an absurd concept?

Sam: We didn't have a car that would make it.