If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (19 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

"Now, I ain't queer or nothin', but as I drove him around, I could feel that he had a... a

magnetism.

But, I ain't queer or nothin'."

We were later treated to a song he produced in Memphis. A woeful tale about Vietnam, this spoken song lauded the soldiers of the United States Marine Corps:

"He was a

real

Deer Hunter..." the lyrics droned. "Not like that

Fonda

Woman..."

As much as we appreciated his efforts, the quality and presentation of the song were so low-grade, that if any of us had made eye contact with each other, it would have been all over. Snickers were hastily disguised as coughs and sneezes.

Still, when Gary wasn't masterminding some self-serving event, he led us around to various backwater places to find a cabin. In more

really

remote areas (as opposed to

regularly

remote), Gary would insist that we wait in the car while he "hollered" at the prospective owners. We were fine with this.

One location, a former first-class resort in the twenties, was now overrun by squatters. As a semi-sheltered suburban boy, I had never encountered anything quite like this. Inside a former "guest cabin" sat the scruffiest, most rampantly bearded, dentally challenged folks you've ever seen. But they were gracious hosts, urging us to "set down awhile" with them on their orange crates or springless mattresses to chat.

HOME SWEET "HOME"

Eventually, November 13, a day before the shoot was to begin, the search led us to a cabin not far from our rented house. Visually, it was ideal. The rustic homestead boasted an overgrown driveway, easily a quarter mile long, that wound down into a feral, isolated valley. It was storybook Tennessee -- something Ma and Pa Kettle would settle into. Practically speaking, however, the place was a bad idea waiting to come to fruition.

As we soon found out, this was no ordinary cabin. There was something of a history to the old place. In the thirties, so the story goes, a young girl named Clara lived in the cabin with her family. One night, a terrible thunderstorm swept through the valley. During that storm, her parents were both brutally and inexplicably murdered. Our stunned girl, escaping that grim fate, wandered aimlessly until she was taken in by neighbors.

To this day, apparently, every time there is a terrible storm, Clara would wander from the Morristown Manor resthome, looking for her parents. She was found, just days before we arrived, wandering in the hills behind our cabin.

Well, Clara or no Clara, the reality of it all was that there was no electricity, no running water and no telephone service in the cabin. Cattle had the run of the place and had managed to deposit easily four inches of manure in every room. There were no doors, the rooms were very small and the ceilings were claustrophobically low. This sucker needed work -- a lot of it. Art Director Dart reckoned it would take about a week of pretty hard work to get it in shape.

But we had a film to shoot, so it was decided that the cabin would be prepped while some simple exterior shots were done. The general edict came down that anyone who wasn't actively filming had to work in the cabin -- actors

included.

There were walls to be knocked out, ceilings to be raised, a trapdoor with a partial basement to be hollowed out and years of newspaper-based wallpaper to be stripped away.

Dart with a circular saw was something to behold. He cut out windows, evened out the front porch and built furniture with "Hitchcockian" flair -- tilted at cock-eyed angles. Ma and Pa Kettle would have been proud.

Brother Don seemed to have a talent for stonework, so he was assigned to put a new craggy face on the fireplace. Sam encouraged him to position the stones above the hearth like angry, jagged teeth.

Eventually, power and telephone lines were installed and the basic work was completed. Our single, rotary telephone sat in a bare, back room. We never did get any kind of plumbing worked out, but it was all part of the charm.

18

"ON YOUR MARKS, GET SET..."

November 14, the race began.

Right from the get go, filming was a comedy of errors, or

terrors,

if you will. Within minutes of leaving for the first location, an abandoned bridge, the production van got lost and we spent a half-hour trying to locate it. No sooner had we found it than Sam drove his "Classic" into a ditch and we had to get a tow truck to haul it out.

The next location was an isolated dirt road. Sam felt that a high, wide shot would be best. We weren't versed in the etiquette of location shooting, so no effort was made to get permission of any kind. We just hopped the fence and set up the camera. Things were going pretty well, until Josh spotted a large bull glaring at the crew.

"Sam... there's a bull." Josh stated, flatly.

"Yeah, hang on," Sam replied, focused on the shot at hand.

"No, Sam, you don't get it. The bull is coming this way."

Sam got it in a hurry and he was chased about a hundred yards by the angry bovine.

Man, what next?

I thought.

A

cliff

was next. About two hours later, Brother Don, scouting for an additional vantage point, lost his footing and tumbled headfirst off a nearby cliff. Apparently he was well enough to get up under his own power, but he was taken to the hospital for some tests. Other than that, day one was very productive.

A week later, shooting a night scene at the same bridge location, Sam had a little run-in with a tree branch. A construction winch was drawn around the side of the bridge to bend a steel girder into position. Unbeknownst to anyone, the cable was also around a large tree branch that promptly snapped when tension was applied to the cable. It flattened Sam -- a limb of easily fifty pounds. He staggered back and sat on the wrecker, dazed. "Sam, you okay?" I asked.

"Why wouldn't I be?" he asked back, a blank look on his face. At first glance he seemed fine, but upon closer inspection he was pale, his lips were white and crusty, and a small amount of blood trickled from his left nostril.

"Well, you don't look so good. What the hell happened?"

"Oh, I just needed to sit down for a... for a little bit..."

With that, he rallied himself and carried on shooting. On the way home that night, he passed out cold.

During the next three months,

Evil Dead

left a path of destruction through the South as wide as Sherman's march to the sea.

Among other things, we destroyed the paint job of a white pickup truck, bent the housing of our 16mm camera, ripped the roof off a rental truck with the help of a low-slung tree branch, and crushed the septic system of my folks' house in northern Michigan.

SAM, I AM

When not plagued by Murphy and his endless series of laws, we did manage to get some work done. For instance, Sam made some remarkable strides as a visually oriented director.

Early on, his directing style became evident. He was never big on shooting a "master" (usually a wide shot, allowing the scene to play from beginning to end). He was much more apt to break scenes down into a series of shots, based on his own indecipherable thumbnail sketches, and shoot only the pieces he needed. This afforded him a great deal of precision, but it's not a method that's applauded by your organically inclined actor. The funny thing was, the actors were all so green (myself included) that none of us really knew the difference.

Sam also wasn't one for the standard medium shot, close-up, over-the-shoulder angles that most film and television shows use to "cover" a scene. As an actor, I found myself being photographed from every conceivable angle. If Sam could have put that camera up my nose, I think he would have done it.

There is an entire sequence in the film where every shot was photographed at a forty-five-degree "Dutch" (tilted) angle. That's quite severe. I must admit, we all thought Sam was crazy when this scheme was revealed, but he was the director. The results were very effective and hold up pretty well, even against the cock-eyed, "MTV style" used regularly today.

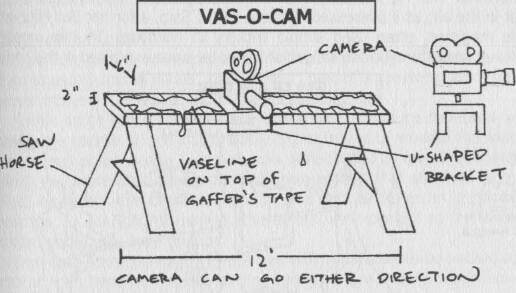

As a result of Sam's boldness, this shoot spawned a number of low-tech but unique camera rigs. Early "tracking" shots were easily accomplished from a wheelchair. When the moves needed to be smoother, or more precise, the

Vas-o-Cam

was used.

This was basically a poor man's dolly. It consisted of several two-by-fours, placed on top of saw horses. The two-by-fours were covered with silver duct tape, thereby providing a smooth, knot-free surface. The tape was then "greased" with household Vaseline. Next, the camera was bolted to a "U"-shaped wood device that laid on top of the Vaseline. Now, the camera could smoothly proceed along its track, stopping on a dime if need be. This device was lightweight, very portable and, even better,

really

cheap.

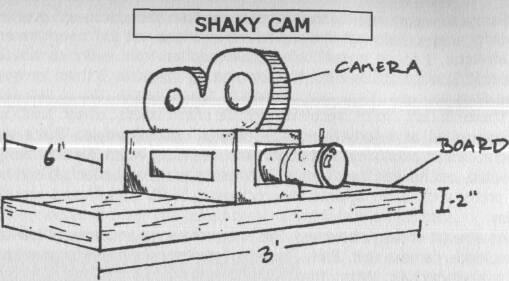

The next invention-of-necessity was the

Shaky Cam.

This was the polar opposite of its big-budget (hence completely unavailable to us) brother, the

Steadi-Cam.

Our version was merely a three-foot hunk of two-by-six board with the camera bolted in the middle. The cameraman slapped on a wide-angle lens, grabbed the board at either end and ran like hell. On film, the end result was an evil, roaming entity that could leap tall shrubs in a single bound.