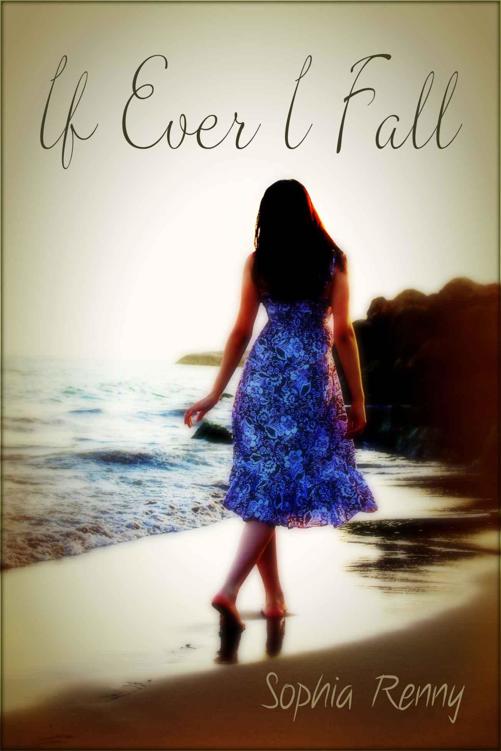

If Ever I Fall (Rhode Island Romance #1)

Read If Ever I Fall (Rhode Island Romance #1) Online

Authors: Sophia Renny

If Ever I Fall

Sophia Renny

Copyright © 2015 Sophia Renny

All

rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or

transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or

other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of

the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical

reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For

permission requests, contact the author via

www.sophiarenny.com

Publisher’s

Note: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are a

product of the author’s imagination. Locales and public names are sometimes

used for atmospheric purposes. Any resemblance to actual people, living or

dead, or to businesses, companies, events, institutions, or locales is

completely coincidental.

Cover

Art Credit: ©iStock.com/Bayram Tunc

Cover

design: © 2015 Sophia Renny

If

Ever I Fall/ Sophia Renny -- 1st ed.

DEDICATION

For M.

Really?

Really.

CONTENTS

The smile on your face lets me know that you

need me

There’s a truth in your eyes saying you’ll

never leave me

The touch of your hand says you’ll catch me if

ever I fall

You say it best when you say nothing at all

When You Say

Nothing at All - Paul Overstreet, Don Schlitz

“You need

to get out more.”

Willa raised her

eyebrows. “I go walking every day unless the weather is horrible. Do you think

we’ve seen the last of the snow yet?”

Collette gave her a

look. “Stop trying to change the subject. You know what I’m talking about.

You’ve been here for over three months. One trip to Newport and another to the

home show is not going out.” She emphasized the last two words with finger

quotes.

It wasn’t the first

time Collette had commented on Willa’s social life, or lack thereof. Yet,

despite her next-door neighbor’s aggressive but well-meaning interference,

Willa always found it difficult to take offense. How could she when the

scolding was spoken with the accent of a fifty-five year old native Rhode

Islander? Willa had fallen in love with the unique, non-rhotic accent within

hours of moving to the Ocean State. If she attempted to capture the sound of

Collette’s voice on paper, it might look something like this:

Stahp trying to change the subject. Ya know what I’m

tawking abowt. You’ve been heah for ovah tree months. One trip to Newpawt and

anothah to the home show is naht goin’ owt.

“I’m a California

girl. Once the weather warms up…”

“When I was your

age, I went out almost every night. Mercy, Audrey and I went clubbing every

Saturday. The doormen knew us by name.”

“Mercy? Seriously?”

“Yeah. Mercy.”

Collette gave a wicked chortle, reminiscing. “Her father would’ve had a heart

attack if he’d found out. All that money he spent to put his kids through

Catholic school. What a waste.”

The older woman set

down her coffee cup with a bang and wagged one finger at Willa. “There you go,

changing the subject again. I’m dead serious about this, Willa Cochrane. You’ve

been holed up in this place for too long. I think you’re getting too

comfortable being inside. I get the reasons why. I really do. But everyone’s

starting to talk.”

“Define everyone.”

“The girls. The

neighbors. Jeannie Clark was asking about you the other day. She says you’re

inside all day. It’s not healthy.”

Now Willa felt a

stir of irritation. “Why should I care what the neighbors think? What business

is it of theirs how I choose to spend my time?”

Collette put up her

hands in defense. “That’s just the way it is around here. We’re not like you

Californians with your fences and gates. We look out for one another. Everyone

loved Pauline. You’re her niece. Of course they’re gonna look out for you, care

about you.”

Willa stood

abruptly, snagged Collette’s half-empty coffee mug along with her own and

carried them to the sink. She stared out the kitchen window. It was looking to

be a clear day for a change, not a cloud in sight. “I’m going for my morning

walk,” she threw over her shoulder, her tone firm. “Do you have to work at the

library today?”

“No. I have the

next two Saturdays off.” There was resignation in Collette’s voice, though her

expression was kind when Willa pivoted toward her.

“I’m heading up to

Dave’s,” Collette announced, pushing her chair back from the table. “They have

chicken thighs on sale this week. Need anything?”

“No, thanks. I took

care of my weekly grocery shopping yesterday. See?” Willa said with a lightness

she didn’t feel, “I actually got in my car and drove somewhere.”

“Not the same

thing, hon.” Collette sent her a wave before heading for the front door. “It’s supper

and a movie night at my place tonight. The girls are coming over. Six o’clock.

See you then.” And she was out the door before Willa could say yes or no.

It

had been bitter cold with a light snow falling when Willa had arrived in Rhode

Island the first week of January. Never having driven in snow before, she

quickly changed her mind about renting a car, instead taking a taxi the

surprisingly short distance from T.F. Green airport to her aunt’s home in

Conimicut.

She’d been seven

years old the one time she’d traveled across the country with her father to

visit Aunt Pauline. Her father had stayed the night of their arrival before

leaving his only child in the keeping of his older sister while he spent the

summer traveling through Europe.

Willa’s

recollections of that summer were fuzzy, but she did remember this: walking

along the beach at Conimicut Point—just as she was doing now, twenty years

later.

It was the first

Saturday in April and, at just after nine o’clock in the morning, already

showing signs of being the first warm day since Willa had arrived in Rhode

Island. Warm meaning that the temperature might venture above fifty degrees

Fahrenheit.

The winds were

calm, but she kept her hands tucked deep inside the pockets of her jacket as

she took what had become her customary route, first heading along the beach on

the northern shore that was flanked by the mouth of the Providence River on one

side, beach homes on the other. When that portion of the beach was no longer

accessible, she turned around, continuing at a brisk pace beyond her starting

place, heading westward toward the point where—when the tides were low—a narrow

sandbar jutted outwards, aiming for the Conimicut Lighthouse, a structure that

had marked the entrance to the Providence River from Narragansett Bay for well

over a century.

Surrounded by water

on three sides, Conimicut Point offered pretty views of Barrington and Bristol

to the west, the taller buildings of Providence visible to the north, and

Patience and Prudence islands to the south. Sometimes, when it wasn’t too

windy, Willa would walk the sandbar as far as she dared, stopping when the

water began to overlap its banks. Collette had warned her not to walk out too

far; the currents were strong and unpredictable in this place where the bay met

the river.

The tide was high

this morning. A cargo ship slogged through the channel, making its way toward

the Port of Providence. Willa watched it for a while, taking deep breaths of

the briny air. Other than an old man she’d glimpsed walking his dog in the

grassy park area, she appeared to be the only person out this morning.

She embraced these

moments. The calm, the quiet. The lack of urgency. There was nowhere that she

had to be, no lectures to give, no papers to grade, no research to be done, no

colleagues to impress. None of that mattered now; perhaps it never would again.

There was just

this: the sand, the water, a lighthouse, a clear blue sky.

She contemplated

her day. Maybe when she returned from her walk she’d bake some cookies to bring

to Collette’s tonight. Then she might watch a couple more episodes of

Lost

;

she’d started that series on Netflix last week and was already on season four.

She hadn’t made up her mind yet on which series to watch next.

Downton Abbey

?

Grey’s Anatomy

?

Scandal

? So many choices for a girl who hadn’t

been allowed to watch entertainment television while in her father’s house. As

she’d grown older, she’d been so immersed in her studies and work that she

simply hadn’t had time.

Now she had all the

time in the world.

And those were just

the television shows. She’d watched at least one movie every day throughout the

cold and gloomy winter months. How decadent it was to burrow inside her down

comforter and immerse herself in the magic of movies. She watched anything and

everything but found herself drawn towards the chick flicks, both classic and

modern. She was fascinated by the lives the female characters led, the way they

dressed and behaved, the way they interacted with the male characters.

Was that what her

life

could

have been like? Was that how she could be living now?

She didn’t dwell on

those questions for long. She didn’t like to think about most things, period,

other than the simple, mindless pleasures that now occupied her days.

Still, as much as

she’d fought against it, her peace of mind was disturbed by Collette’s words

from earlier that morning. Until now, Willa hadn’t given a second thought to

how outsiders might interpret her behavior since she’d moved into the

neighborhood. For the first time in her life, she was officially on her own,

beholden to no one. Selfish as it might appear, she’d only wanted to focus on

herself, in a way she’d never been able to do before. Why should she feel

guilty about that?

She was supposed to

be in mourning, after all. She was a young woman who had lost both her father

and her aunt—her only family—within the last six months.

She’d scarcely known

her aunt. She hadn’t seen Pauline Cochrane since that long ago summer. Other

than the annual exchange of birthday and holiday cards—sent through her father—Willa

hadn’t communicated with her either.

As for her father…

The profound relief

she’d felt when she’d been informed that her father had died… She could never

share that with anyone.

The instant Dean

Stone had left Willa’s office after conveying the news of Derek Cochrane’s

passing, Willa had vaulted from her chair and spun in circles around the room,

arms outspread, palms up, fingers tingling. The pressing down feeling she’d

carried with her since she was five years old evaporated instantly. It was as

if she’d been a marionette affixed to taut strings all those years, performing

to the puppeteer’s tune. Those strings had been severed at last.

Euphoria had

crashed into uncertainty all too quickly. She’d collapsed to the floor in a

corner of her office, hugged her knees against her chest and slowly rocked back

and forth. She might have been freed from her father’s restraints, but now she

wasn’t sure how to move forward on her own. It was as if her limbs were unable

to carry her without those controlling strings attached.

In the days that

followed, throughout the funeral arrangements and the ceremony itself, one

thought had gained momentum and clarity until it had consumed her every waking

moment: she needed to go somewhere, anywhere, far away from the classes, the

research, the books, the academia that she’d grown to hate.

Out of the blue

came a letter from a law office in Warwick, Rhode Island, informing her of

Pauline Cochrane’s passing, and that she, Pauline’s only living relative, was

named sole beneficiary of her aunt’s estate.

Willa would have

liked to have left her job immediately, to hell with the repercussions. But

there had been contracts to wade through, obligations both verbal and written,

many of them commitments her father had made on her behalf without her

knowledge.

When it was over,

once she’d been able to pack up her belongings and ship them to her new home,

once she’d closed the door to her office for the last time, she’d felt

physically and emotionally exhausted, more tired than she’d ever felt in her

life.

All she’d wanted

was rest and quiet. And these past few months in her new home had provided just

that. It was absolute heaven. Doing nothing. Thinking of nothing. Just

sleeping, baking, watching movies and television, taking long walks.

A simple, logical

self-analysis told her that she was going through the stages of grief. It was

perfectly normal to isolate herself from her loss. But only Willa knew what she

was truly mourning: the loss of her own self, the loss of the little girl she

could have been, the young woman she might have been. She hadn’t reached the

anger stage yet, and she didn’t think she was depressed. She could spend days

analyzing the dichotomy of her emotions, the sense of freedom and peace

juxtaposed with feelings of loss and regret. But she didn’t want to.

Maybe she

was

becoming a recluse.

Leave it to

Collette to pry open Willa’s cocoon; the woman had been blunt and brash from

the moment Willa had met her.

Through her aunt’s

lawyer, Willa had learned that Collette Fournier had been Pauline’s next-door

neighbor for over twenty years. She’d been appointed by Pauline as executor of

Pauline’s estate. Communicating through the lawyer, Willa had notified Collette

of her plans to move into the house and what day she’d arrive.

As soon as the taxi

had pulled into the narrow driveway on that cold evening back in January, a

short, plump woman wearing a purple coat over hot pink snow pants tucked inside

winter boots came trudging through the snow that filled the side yard between

Pauline’s home and a smaller, single-story cottage next door.

“You must be

Willa,” she hollered as soon as Willa opened the car door. “I’m Collette

Fournier. Great to meet ya! Come on. Let’s get your things and you inside the

house. It’s freezing out here. Hey, Brian. How are ya? How’s your ma?”

The older woman

chatted amiably with the taxi driver as she helped him hoist Willa’s two heavy

suitcases from the trunk and then led him towards Pauline’s house. Willa, with

her shoulder bag slung over one arm and her smaller carry-on in tow, followed

them with tentative steps as they took a brick pathway along the left side of

the house. She could tell that the pathway had been shoveled recently, but the

freezing temperature had already iced over sections of the fresh batch that had

since fallen.