If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (33 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

By 1694, the English state had decided to make money out of marriage, and a tax was introduced. Clandestine marriage, a ceremony performed in secret so that anyone objecting to the union was given no chance to speak, was gradually stamped out. The Marriage Act of 1753 tightened things up further, with weddings allowed only between 8 a.m. and midday, as part of the Sunday service. This explains why a wedding meal is still known as a ‘breakfast’: for centuries it took place in the morning.

Although he lived in the age when love was supposed to play a part, Charles Darwin took a scientific and pragmatic view of a marriage proposal. Despite the annoyance of losing the ‘freedom to go where one liked’ and the ‘conversation of clever men at clubs’, and of having ‘less money for books &c’, he decided that ‘a nice soft wife on a sofa with a good fire’ would be good for his health. So, he concluded, ‘Marry Q.E.D.’

33 – Dying (and Attending Your Own Funeral)

My dearest dust, could not thy hasty day

Afford thy drowsy patience leave to stay

One hour longer: so that we might either

Sit up, or go to bed together?

Lady Catherine Dyer’s epitaph for

her husband William, 1641

These last chapters have described how people’s homes intersected with the great wide world outside. That relationship between public and private life continues even after a person’s death.

The age at which people can expect to die has been gradually creeping upwards since Norman times. The median age of everyone in Britain today is thirty-eight, whereas in fourteenth-century society it was just twenty-one. Only 5 per cent of fourteenth-century individuals made it to the advanced age of sixty-five. People in the past therefore were considered to have reached maturity much more quickly. Boys as young as seven were expected to work, and could from that age be hanged for stealing. Youthful societies tend to be more violent, more brutal – but maybe, also, more vigorous and more creative.

But there are also some surprising continuities between today and the past. Even in the Tudor and Stuart periods old age began at fifty or sixty, probably a greater age than one might

expect given that children became adults much sooner. We’ve been misled by the figures for average life expectancy into thinking that everyone expected to die at about forty. They didn’t. While people were used to their fellows dying at a young age, this was considered unfortunate. ‘Threescore years and ten’ was the perceived ‘natural’ length of a life. Even then the elderly were a significant consumer group, and purchasers of a variety of age-related paraphernalia. Henry VIII had ‘gazings’, or spectacles, with lenses of rock crystal from Venice, and also a couple of wheelchairs (‘chairs called trams’).

The sufferings of old people sound similar throughout the centuries, while the complaints about them sound ever thoughtless. The Jacobean Thomas Overbury ranted about the ‘putrified breath’ of old men, their annoying habit of coughing after each sentence, and of ‘wiping their drivelled beards’. ‘Elderly gentlewomen are useful persons to make tea, and take snuff, and play low whist,’ and not much else, complained the magazine

John Bull

in 1821.

Old age was clearly not only a physical problem but a social one too. Lady Sarah Cowper in the early 1700s sounds remarkably modern when she complains: ‘I seem to be laid by with all imaginable contempt as if I were superannuate at 57 past conversation.’ Yet she was also (inconsistently) contemptuous about her contemporaries who sought to look younger than their years. One acquaintance

affects the follies and airs of youth, displays her breasts and ears, adorns both with sparkling gems while her eyes look dead, skin shrivell’d, cheeks sunk, shaking head, trembling hands, and all things bid shut up shop.

Women have always been affected more by old age than men. A lifetime of heavy labour and poor diet would have made the effects of the menopause – decreased bone density, excess hair and the loss of teeth – even more exaggerated, so a Tudor woman would have quickly passed from youthful desirability

to a witch-like appearance. The medical theory of the four humours worked against them too: once they were no longer producing milk or monthly blood, their bodies were thought to be ‘drier’ and therefore more like men’s. They were considered, ‘under the stopping of their monthly melancholic flux’, to have turned into second-class men, without men’s strength or reason.

After your death your intimate history was still not quite over: you had to experience your own funeral. There was an average of seven days between death and burial, for example, for those buried in the eighteenth-century Christ Church in Spitalfields, London. That final week would be spent in your own living room, and family and friends would come to visit. The Stuart wig-maker, Edmund Harrold, described what happened after the sad death of his wife ‘in my arms, on pillows’. His community helped him to make heartbreaking small decisions about her clothing – ‘I have given her workday cloth[e]s to mother Bordman and Betty Cook our servant’ – and the big one about what to do with her body: ‘Now relations thinks best to bury her at [the] meetin[g] place in Plungeon Field, so I will.’

The passing of a medieval earl required the turn-out and lineup of all his friends, servants, supporters, tenants and hangers-on. The remnants of that tradition could still be seen in play at the death of Andrew Cavendish, eleventh Duke of Devonshire, in 2004, when scores of servants lined up along the drive at Chatsworth House to salute his hearse. If you had no friends, your heirs could buy them for you. A staggering 31,968 people attended the funeral of the Bishop of London in 1303; many were paid to turn up. In remote Hertfordshire the ancient custom of ‘sin-eating’ endured in the 1680s. Poor people would be hired to attend and ‘to take upon them all the sins of the party deceased’.

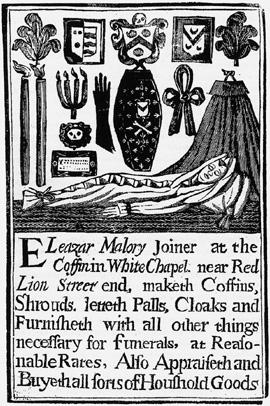

From 1660 it became illegal to be buried in anything other than a woollen shroud. The law was passed to support the British wool industry against the slave-serviced and aggressively expanding cotton industry. The profession of undertaker

developed in the late seventeenth century to co-ordinate the activities of the coffin-maker, coach-hire company and upholsterer; previously all had been commissioned separately by the dead person’s family. The upholsterer was required to hang the living rooms of a house in mourning with black fabric; your heirs might also order a ‘funerary hatchment’ from the College of Arms (a painted diamond showing your family’s arms) to hang over the front door. The 1666 funeral directions for Sir Gervase Clifton, of Clifton Hall, Nottinghamshire, illustrate how his living rooms were decorated for the occasion:

The trade card of one of the earliest professional undertakers. They undertook to co-ordinate the coach-hire firm, upholsterer and apothecary, all of whom had previously been commissioned separately

The hall to be hanged with a breadth of black baize

The passage into my lady’s bedchamber to be hanged with a breadth of baize

The great dining room, where the better sort of mourners are to be, to be hanged with a breadth of baize.

The body to be there.

Undertakers obviously had an interest in encouraging people to put on a show, and eventually, as a super-successful Victorian profession, they became subject to ridicule for their pompous and overbearing attitudes.

The display of the corpse of an important personage was a hugely important ritual. But sometimes grand funerals could take several weeks to arrange. The actual body would have rotted before then, so a wax or wooden image or ‘representation’ was used to stand in for it. The tail end of this custom can be seen in the display at Westminster Abbey of the curious waxworks representing Charles II, William III and Mary II, and Queen Anne. Making these funerary figures was the origin of Madame Tussaud’s business.

The early embalming of bodies was a very inexact science, and if it went wrong the build-up and explosion of gases in the coffin could be spectacular and damaging. Charles the Bald, the Holy Roman Emperor, died away from home in 877. His attendants ‘opened him up’, ‘poured in such wine and aromatics as they had’ and began to carry his body back towards St Denis. But the stench of the putrefying corpse caused them to ‘put him in a barrel which they smeared with pitch’. When even this failed, they carried him no further and buried him at Lyons.

Removing the internal organs was a wise precaution against putrefaction: this is why Jane Seymour’s viscera are buried at Hampton Court Palace (where she died) rather than at Windsor Castle (where she was officially buried). It was said that Henry VIII’s body exploded as it lay overnight in its coffin at Syon Abbey, a staging post on his final journey towards his own burial at Windsor, and that dogs licked up matter dripping onto the church floor. (We might add that dogs also licked up the blood of the biblical Ahab as a punishment for falling under the influence of his pagan wife Jezebel. So perhaps this story was spread about by the supporters of Katherine of Aragon, still trying to get Henry back for his treatment of his first wife.)

Elizabeth I, famously virginal, lost her final battle to prevent

her body from being penetrated by a man. Her Privy Councillors, well aware of her wish not to be autopsied, had their attention distracted by the business of proclaiming James I as her successor. Contrary to her orders, Secretary Cecil gave ‘a secret warrant to the surgeons’, let them into her chamber, and there ‘they opened her which the rest of the council afterwards passed over, though they meant it not so’.

These surgeons removed her entrails, but the techniques for preservation were still inadequate. Elizabeth’s body was stuffed with herbs, wrapped in cerecloth, nailed up in a coffin and left at the Palace of Whitehall to be watched over by her ladies-in-waiting. But that night Lady Southwell, sitting up in vigil with the dead queen, was horrified to experience the ‘body and head brake with such a crack, that [it] splitted the woods’.

A century later, embalming was more effective when Mary II met her death from smallpox in 1694. ‘Rich gums and spices to stuff the body’ kept her safe from the worst ravages of decay until her funeral. Charles I’s corpse also survived well after his execution in 1649. When his coffin was opened in 1813, his body was discovered to have been

carefully wrapped up in cere-cloth, into the folds of which a quantity of unctuous or greasy matter, mixed with resin, as it seemed, had been melted, so as to exclude, as effectually as possible, the external air.

This had been so effective that, when it was unwrapped, ‘the left eye, in the first moment of exposure, was open and full, though it vanished almost immediately’.

The surgical advances made by Dr John Hunter in the eighteenth century included a new expertise in preserving cadavers which rendered the wax representation obsolete. One of Dr Hunter’s associates, a Dr Martin Van Butchell, had his own dead wife’s blood vessels injected with carmine and glass eyes inserted. He kept her in his sitting room and introduced her to visitors to the house. It was only the second Mrs Van Butchell who finally insisted that her predecessor should leave.

Meanwhile, those lower down in society put up with burials that ranged from pragmatic (plague victims dissolved in pits of quicklime) to the ignominious (an unmarked mass grave created after a battle). But a dead person of any pretension would commonly lie in their living room while mourners were summoned by the tolling of the parish church’s ‘passing bell’ to pay their respects, bringing sprigs of rosemary or rue.

It’s true that the increasing intricacy of mourning dress and the petty rules regarding its timing began to make the Victorian cult of grief appear overblown and insincere. But the great advantage of the funeral-with-a-cast-of-thousands was its cathartic, crowd-pleasing quality. Now our corpses are shuffled off quietly to the cemetery or incinerator, and we’re embarrassed by loss and sorrow. If this book can teach us anything, though, it’ll be the fact that this might change yet again.