If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (31 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

30 – Sitting Up Straight

When we rejoined the ladies in the drawing room, Princess took me by the arm and hand and led me into a corner. Most intimate and cosy. Is flirtatious. I tried not to press her hand back, lest

lèse-majesté

.

James Lees-Milne on meeting Princess

Michael of Kent, 23 August 1983

When there are guests in your living room, there’s always been a tension between paying respect – which means keeping at a suitable distance from another individual’s personal space – and offering intimacy. As a form of flattery intimacy trumps respect, because it implies the dropping of barriers and the creation of trust. Hence the informal barbecues for world leaders that George W. Bush used to host at Camp David.

Henry VIII would likewise drape an arm round the shoulders of a favoured ambassador or courtier. But then – just like a lion – he could round upon and maul a man just as soon as he became overfamiliar: the king ‘could not abide to have any man stare in his face when he talked with them’.

This knife-edge that has to be walked between respect and intimacy creates another danger: manners that are simply too nice. Then as now, being overly well-mannered is unmanly and debilitating. In a Stuart snuff shop full of fops, ‘bows and cringes

of the newest mode were here exchanged twixt friend and friend, with wonderful exactness’. It’s a recognisable description of high camp. Behaviour books from every period recommend striking a balance between manners and brutality, but no one can ever define exactly what that balance should be. Learning it at the knee of one’s mother is the mark of a true gentleman, and the pretenders who have to read about such things in books never quite catch up.

In his classic

Über den Prozess der Zivilisation

(1939), Norbert Elias made a striking link between fancy manners and political absolutism. He traced a path through history which saw societies dominated by independent warriors, or knights, gradually give way to courtly ones, in which a single dominant figure lords it over everyone else. The knights were uncouth and violent – as they had to be, to win power. They used brute physical force to seize the food and land to which they felt entitled. The courtiers of an absolutist king did not win their power through force, because the physical needs of the upper classes were now met by a taxation system. Instead, they competed with each other through their exquisite, nuanced and civilised behaviour.

If we follow in Elias’s footsteps from the medieval to the modern period, we can chart the arrival of new concepts such as ‘shame’ or ‘embarrassment’, emotions that had a much weaker hold on medieval psyches. Elias describes ‘shame’ as ‘a fear of social degradation … which arises characteristically on those occasions when a person who fears lapsing into inferiority can avert this danger neither by direct physical means nor by any other form of attack’. Bowing, hat etiquette, proposing toasts, dancing: all provided a Tudor or Stuart with new means of humiliating his enemies or winning admiration from his friends.

In the grand, formal and stately great chambers of Hardwick Hall, or its seventeenth-century successors, one was expected to behave in a grand, formal and stately manner. It was unthinkable for a servant on duty in these rooms to address his master

without making a bow. Good servants were expected to be:

so full of courtesy as not a word shall be spoken by their masters to them, or by them to their masters, but the knee shall be bowed … their master shall not turn sooner than their hat will be off.

And this kind of behaviour was not just for servants. The fifteen-year-old wife addressed in the advice book

Le Ménagier de Paris

is told, literally, not to look at another man, or even another woman:

Keep your head upright, eyes downcast and immobile. Gaze four

toises

(about 24 feet) straight ahead and toward the ground, without looking or glancing at any man or woman to the right or left, or looking up, or in a fickle way casting your gaze about.

In the reception rooms of a Tudor house, it would be equally unthinkable for two people of different rank to be seated in the same kind of chair: inevitably the more elaborate chair, placed nearer to the fire, would be occupied by the more senior person. Even walking up and down the long gallery had its own terms of engagement, described in this essay called

Rules to be Observed in Walking with Persons of Honour

(1682):

If you walk in a Gallery … be sure to keep the left hand; and without affectation or trouble to the Lady, recover that side at every turn. If you make up the third in your walk, the middle is the most honourable place, and belongs to the best in the company, the right hand is next, and the left in the lowest estimation.

And yet it’s worth remembering that all this was a performance for the benefit of others. When alone, people could, and did, behave more naturally. Off duty, you might ‘loosen your garters or your buckles, lie down upon a couch, or go to bed, and welter in an easy chair … negligences and freedoms which one can take only when quite alone’. Queen Elizabeth I, always very conscious of her image, would never allow herself to be seen in an un-queenly state. She had the windows overlooking the Privy Garden at Hampton Court blocked up so that on cold

mornings, when she liked to lollop about vigorously in the gardens ‘to catch her a heat’, she could do so unobserved.

Britain’s political revolution of the seventeenth century caused another revolution: in body language. Charles I was defeated in battle and eventually executed by his own subjects for pushing his royal prerogative too far. During the period after his defeat, when the English Commonwealth replaced monarchical rule, a new form of greeting began to appear that reflected the fact that the social hierarchy had been destroyed. The doffing of the hat to one’s superior was replaced by a form of greeting which assumed that both parties were equals: England’s new, democratic rulers prided themselves upon refusing to bow, insisting instead upon shaking hands.

Once absolute political rule began to decline, the most extreme excesses of courtly behaviour and manners also lay in the past. Even after Charles II had been ‘restored’ to England’s throne, a series of further revolutions saw the power of the Stuart kings eroded in the much more limited job descriptions of the Hanoverian kings. Likewise, the new, sociable age of the eighteenth century was less formal than the previous one in its behaviour. The Georgians aimed to create an atmosphere of relaxation rather than stern stateliness: as Lord Chesterfield put it, ‘one ought to know how to come into a room, speak to people, and answer them, without being out of countenance, or without embarrassment’.

Chesterfield still paid serious attention to body language, but now the emphasis was on elegance rather than formality. ‘I desire you will particularly attend to the graceful motion of your arms,’ he recommended, in ‘the manner of putting on your hat, and giving your hand’. Conduct was even more relaxed across the Atlantic. ‘Formal compliments and empty ceremonies’ did nothing for Martha Washington, chatelaine of the US’s presidential household from 1789. ‘I am fond only of what comes from the heart,’ she said.

Clothing also dictates body language, and for women the wearing of stays encouraged a stiff and upright carriage. It’s handy to have something to do with the hands placed on display by the wearing of hooped skirts, so Georgian accessories were brought into service: ‘snuff, or the fan supplies each pause of chat’. The French today are much bigger kissers than the English, but this was not so in the eighteenth century. Then, a Swiss visitor wrote home from England: ‘let not this mode of greeting scandalise you … it is the custom of this country, and many ladies would be displeased should you fail to salute them thus’.

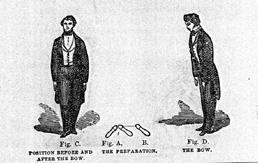

Hints on how to bow, from

A Complete Practical Guide to the Art of Dancing

(1863)

In the nineteenth century, though, a certain pursing of the lips occurred, and the free and easy Georgian manners began to be seen as vulgarly uninhibited. Ironically, it was partly the medical advances of the Enlightenment which seemed to push women back into a more ceremonial age. The realisation that women were fundamentally different from, rather than a weaker version of, men led to the idea that ladies were fragile things needing constant protection. This was achieved by turning attention to decorum and manners. Ladies were considered to have mislaid the ability to make jokes, or even to walk; thus the now-lost art of leaning upon a gentleman’s arm was born. This new morality

brought to an end the kind of entertainments that had enlivened Georgian drawing rooms. There was no more dubious gambling or dancing. ‘Waltzing is so dangerous’, wrote the anonymous author of

Advice to Governesses

(1827), ‘that I wonder how a prudent mother can tolerate the amusement.’

In the late Victorian period, America and Europe clash in Edith Wharton’s historical novel

The Buccaneers

. ‘The friendly bustle of the Grand Union, the gentlemen coming in from New York … with the Wall Street news’ were sadly lacking in the cold, aristocratic British drawing rooms which a group of young American heiresses nevertheless wish to conquer. The young conquistadors found themselves ‘chilled by the silent orderliness’ of the British household. The maid-servants were ‘painfully unsociable’, and they ‘were too much afraid of the cook ever to set foot in the kitchen’.

This makes British drawing rooms sound stiff and retrograde, but they had at least become the part of the house dominated by women. Once, the master of the house had controlled his family’s social life, just as he did its financial or reproductive plans, but somewhere along the way men relinquished their role as hosts. In 1904, Hermann Muthesius explained that

the Englishwoman is the absolute mistress of the house, the pole round which its life revolves … the man of the house, who is assumed to be engrossed in his daily work, is himself to some extent her guest when at home. So the drawing-room, the mistress’s throne-room, is the rallying-point of the whole life of the house.

Muthesius also noted that the woman ‘keeps an eye on all exchanges with the outer world, issues invitations and receives and entertains guests’, and this is the topic of the next chapter.

31 – A Bright, Polite Smile

Everyone complains of the pressure of the company, yet all rejoice at being so divinely squeezed.

François de La Rochfoucauld

on London parties, 1784

Everyone has seen the bright, polite and slightly false smile pasted upon the lips of a host and hostess. Now we move on to the actual hour of a living-room performance, from the amazing conspicuous consumption of the Stuart masque to the formal Victorian fifteen-minute call.

Being sociable has always been something of a duty, and the line between the convivial and the tedious is a fine one. Eleanor Roosevelt calculated that in the year of 1939 she had shaken hands with 14,046 people. ‘My arms ached,’ she recollected, ‘my shoulders ached, my back ached, and my knees and feet seemed to belong to someone else.’ But the people whose hands were shaken were doubtless pleased with their experience. Generosity, gift-giving and hospitality are essential for holding society together.

How to entertain your guests? Well, Tudor or Stuart guests might have been treated to a formal masque, a kind of dramatic and musical entertainment involving professional and amateur performers alike. Henry VIII thought it amusing to appear in disguise at one of Cardinal Wolsey’s parties, and to make the

ladies dance with him. On another court occasion, Anne Boleyn made her debut in a masque called ‘

Le Chateau Vert

’ in the character of ‘Perseverance’ (this turned out to be most appropriate in light of the subsequent lengths to which she would go to bag the king). Singing or musical entertainments were always popular, and Henry VIII poached some of the best singers from Cardinal Wolsey’s boys’ choir for his own. Masques continued into the next century, getting more and more lavish or even debauched: at one performance for the rather seedy James I, the actress playing the Queen of Sheba smeared cream and jelly all over the drunken King Christian of Denmark. The two ladies supposed to be playing Faith and Hope drank too much and were found spewing behind the scenes.