In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (8 page)

Read In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind Online

Authors: Eric R. Kandel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

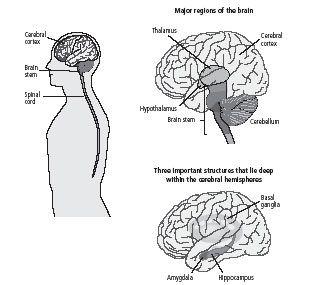

3–3

The central nervous system.

The deficiencies in our description would probably vanish if we were already in a position to replace the psychological terms by physiological or chemical ones….

Although most psychoanalysts in the 1950s thought of mind in nonbiological terms, a few had begun to discuss the biology of the brain and its potential importance for psychoanalysis. Through the Krises, I met three such psychoanalysts: Lawrence Kubie, Sidney Margolin, and Mortimer Ostow. After some discussion with each of them, I decided in the fall of 1955 to take an elective at Columbia University with the neurophysiologist Harry Grundfest. At the time, the study of brain science was not an important discipline at many medical schools in the United States, and no one on the NYU faculty was teaching basic neural science.

I WAS STRONGLY SUPPORTED IN THIS DECISION BY DENISE

Bystryn, an extremely attractive and intellectually stimulating Frenchwoman I had recently started to date. While I had been taking Hausman’s anatomy course, Anna and I had started to drift apart. A relationship that had been very special for both of us when we were together in Cambridge did not work as well with her in Cambridge and me in New York. In addition, our interests were beginning to diverge. So we parted ways in September 1953, soon after Anna graduated from Radcliffe. Anna now has a highly successful practice of psychoanalysis in Cambridge.

I subsequently had two serious but brief relationships, each of which lasted only a year. As the second relationship was breaking up, I met Denise. I had heard about her from a mutual friend, and I called her to ask her out. As the conversation progressed, she made it clear that she was busy and not particularly interested in meeting me. I nevertheless persisted, pulling out one stop after another. All to no avail. Finally, I dropped the fact that I came from Vienna. Suddenly, the tone of her voice changed. Realizing that I was European, she must have thought that I might not be a complete waste of her time and she agreed to meet with me.

When I picked her up at her apartment on West End Avenue, I asked her whether she wanted to go to a movie or to the best bar in town. She said she would like to go to the best bar, so I took her to my apartment on Thirty-first Street near the medical school, which I shared with my friend Robert Goldberger. When we moved into the apartment, Bob and I renovated it and built a very nicely functioning bar, certainly the best among our circle of acquaintances. Bob, a connoisseur of scotch, had a fine collection, even including some single-malt scotches.

Denise was impressed with our woodworking skill (mostly Bob’s), but she did not drink scotch. So I uncorked a chardonnay and we spent a delightful evening in which I told her about life in medical school and she talked about her graduate work in sociology at Columbia. Denise’s specific interest was in using quantitative methods to study how people’s behavior changed over time. Many years later, she applied this methodology to the study of how adolescents become involved in drug abuse. Her epidemiological work was of landmark proportions: it became the basis for the gateway hypothesis, which holds that particular developmental sequences underlie progressively more severe drug use.

Our courtship was amazingly smooth. Denise combined intelligence and curiosity with a wonderful capability for beautifying everyday life. She was a fine cook, had excellent taste in clothing—some of which she made herself—and liked to surround herself with vases, lamps, and art that enlivened the space in which she lived. Much as Anna influenced my thinking about psychoanalysis, Denise influenced my thinking about both empirical science and the quality of life.

She also strengthened in me the sense of being a Jew and a Holocaust survivor. Denise’s father, a gifted mechanical engineer, came from a long line of rabbis and scholars and had trained as a rabbi in Poland. He left Poland when he was twenty-one years old and went to Caen in Normandy, France, where he studied mathematics and engineering. Although he became an agnostic and stopped going to synagogue, he kept an impressive collection of Hebrew religious texts in his large library, including the Mishnah and a Vilna edition of the Talmud.

The Bystryns stayed in France throughout the war. Denise’s mother helped her husband escape from a French concentration camp, and they both survived the war by hiding from the Nazis in the small town of St.-Céré, located in the southwest. During a good part of that time, Denise was separated from her parents, hidden in a Catholic convent in Cahors, about fifty miles away. Denise’s experiences, though much more difficult, paralleled mine in a number of ways. Over the years, our memories of our individual experiences in a Europe dominated by Hitler proved to be enduring for each of us and brought us closer together.

One incident in Denise’s life made an indelible impression on me. In the few years she spent in the convent, no one but the Mother Superior knew that she was Jewish and no one put any pressure on her to convert to Catholicism. But Denise felt awkward in relation to her classmates because she was different. She did not go to confession, nor did she take holy communion at mass every Sunday. Denise’s mother, Sara, became uncomfortable about her daughter’s standing out in this way and was afraid that her true identity might be uncovered, which could endanger her. Sara discussed this dilemma with Denise’s father, Iser, and they decided to have Denise baptized.

Sara traveled on foot and by bus the almost fifty miles from their hiding place to the convent in Cahors. When she arrived at the convent, she stood in front of the heavy, dark wooden door and was about to knock on it and announce her presence, when at the last moment she could not bring herself to convey the fateful decision. She turned around without entering the convent and walked back home, certain that her husband would be furious that she had not lessened the danger to their daughter. When she entered the house in St.-Céré, she found that Iser was immensely relieved. All the time that Sara had been gone, he had obsessed about the error he had made in agreeing to allow Denise to be converted. Despite the fact that Iser did not believe in God, he and Sara were very proud to be Jews.

In 1949 Denise, her brother, and her parents immigrated to the United States. Denise attended the Lycée Français de New York for one year and was admitted to Bryn Mawr College as a junior at age seventeen. On graduating from Bryn Mawr at nineteen, she enrolled as a graduate student in sociology at Columbia University. When we met in 1955, she had started research for her Ph.D. thesis in medical sociology with Robert K. Merton, one of the great contributors to modern sociology and a founder of the sociology of science. Her thesis was a study of the career decisions of medical students based on an empirical longitudinal survey.

A few days after I graduated from medical school, in June 1956, Denise and I married (figure 3–4). After a brief honeymoon in Tanglewood, Massachusetts, where I spent some time studying for the national boards in medicine—a point that Denise has never allowed me to forget—I started a one-year internship at Montefiore Hospital in New York City while Denise continued her doctoral research at Columbia.

3–4

Denise at our wedding in 1956. She was twenty-three and a graduate student in sociology at Columbia University. (From Eric Kandel’s personal collection.)

Denise sensed, perhaps more than I did, that my idea of examining the biological basis of mental function was original and bold, and she urged me to explore it. I was concerned, however. Neither of us had any financial resources, and I thought it essential to have a private practice in order to support us. Denise simply gave the issue of money short shrift. It was of no importance, she insisted. Her father, who had died a year before I met her, had advised his daughter to marry a poor intellectual because such a man would value scholarship above all and would strive to pursue exciting academic goals. Denise believed she was following that advice (she certainly married someone who was poor), and she always encouraged me to make bold decisions that favored my doing something genuinely new and original.

Biology is truly a land of unlimited possibilities. We may expect it to give us the most surprising information, and we cannot guess what answers it will return in a few dozen years…. They may be of a kind which will blow away the whole of our artificial structure of hypotheses.

—Sigmund Freud,

Beyond the Pleasure Principle

(1920)

I

entered Harry Grundfest’s laboratory at Columbia University for a six-month elective period in the fall of 1955, hoping to learn something about higher brain functions. I did not anticipate embarking on a new career, a new way of life. But my very first conversation with Grundfest gave me reason to reflect. In that conversation I described my interest in psychoanalysis and my hope of learning something about where in the brain the ego, the id, and the superego might be located.

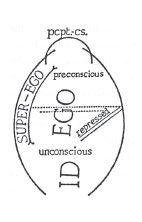

My desire to find these three psychic agencies had been sparked by a diagram Freud published in the course of summarizing his new structural theory of mind, which he developed in the decade 1923 to 1933 (figure 4–1). That new theory maintained his earlier distinction between conscious and unconscious mental functions, but it added three interacting psychic agencies: the ego, the id, and the superego. Freud saw consciousness as the

surface

of the mental apparatus. Much of our mental function is submerged below that surface, Freud argued, just as the bulk of an iceberg is submerged below the surface of the ocean. The deeper a mental function lies below the surface, the less accessible it is to consciousness. Psychoanalysis provided a way of digging down to the buried mental strata, the preconscious and the unconscious components of the personality.

4–1

Freud’s structural theory. Freud conceived of three main psychic structures—the ego, the id, and the superego. The ego has a conscious component (perceptual consciousness, or

pcpt.-cs

.) that receives sensory information and is in direct contact with the outside world, as well as a preconscious component, an aspect of unconscious processing that has ready access to consciousness. The ego’s unconscious components act through repression and other defenses to inhibit the instinctual urges of the id, the generator of sexual and aggressive instincts. The ego also responds to the pressures of the superego, the largely unconscious carrier of moral values. The dotted lines indicate the divisions between those processes that are accessible to consciousness and those that are completely unconscious. (From

New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

[1933]).

What gave Freud’s new model a dramatic turn was the three interacting psychic agencies. Freud did not define the ego, the id, and the superego as either conscious or unconscious, but as differing in cognitive style, goal, and function.

According to Freud’s structural theory, the ego (the “I,” or autobiographical self) is the executive agency, and it has both a conscious and an unconscious component. The conscious component is in direct contact with the external world through the sensory apparatus for sight, sound, and touch; it is concerned with perception, reasoning, the planning of action, and the experiencing of pleasure and pain. In their work, Hartmann, Kris, and Lowenstein emphasized that this conflict-free component of the ego operates logically and is guided in its actions by the reality principle. The unconscious component of the ego is concerned with psychological defenses (repression, denial, sublimation), the mechanisms whereby the ego inhibits, channels, and redirects both the sexual and the aggressive instinctual drives of the id, the second psychic agency.

The id (the “it”), a term that Freud borrowed from Friedrich Nietszche, is totally unconscious. It is not governed by logic or by reality but by the hedonistic principle of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. The id, according to Freud, represents the primitive mind of the infant and is the only mental structure present at birth. The superego, the third governor, is the unconscious moral agency, the embodiment of our aspirations.

Although Freud did not intend his diagram to be a neuroanatomical map of mind, it stimulated me to wonder where in the elaborate folds of the human brain these psychic agencies might live, as it had earlier stimulated the curiosity of Kubie and Ostow. As I mentioned, these two psychoanalysts with a keen interest in biology had encouraged me to study with Grundfest.

Grundfest listened patiently as I told him of my rather grandiose ideas. Another biologist might well have dismissed me, wondering what to do with this naïve and misguided medical student. But not Grundfest. He explained that my hope of understanding the biological basis of Freud’s structural theory of mind was far beyond the grasp of contemporary brain science. Rather, he told me, to understand mind we needed to look at the brain one cell at a time.

One cell at a time! I initially found those words demoralizing. How could one address psychoanalytic questions about the unconscious motivation of behavior, or the action of our conscious life, by studying the brain on the level of single nerve cells? But as we talked I suddenly remembered that in 1887, when Freud began his own career, he had sought to solve the hidden riddles of mental life by studying the brain one nerve cell at a time. Freud started out as an anatomist, studying single nerve cells, and had anticipated a key point of what later came to be called the neuron doctrine, the view that nerve cells are the building blocks of the brain. It was only later, after he began treating mentally ill patients in Vienna, that Freud made his monumental discoveries about unconscious mental processes.

I found it ironic and remarkable that I was now being encouraged to take that journey in reverse, to move from an interest in the top-down structural theory of mind to the bottom-up study of the signaling elements of the nervous system, the intricate inner worlds of nerve cells. Harry Grundfest offered to guide me into this new world.

I HAD SPECIFICALLY SOUGHT TO WORK WITH GRUNDFEST

because he was the most knowledgeable and intellectually interesting neurophysiologist in New York City—indeed, one of the best in the country. At the age of fifty-one, he was at the peak of his very considerable intellectual powers (figure 4–2).

Grundfest had obtained a Ph.D. in zoology and physiology at Columbia in 1930 and continued there as a postdoctoral fellow. In 1935 he joined the Rockefeller Institute (now Rockefeller University) to work in the laboratory of Herbert Gasser, a pioneer in the study of electrical signaling in nerve cells, a process at the very heart of how nervous systems function. At the time that Grundfest joined him, Gasser was at the high point of his career, having just been appointed president of the Rockefeller Institute. In 1944, while Grundfest was still in his laboratory, Gasser was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

4–2

Harry Grundfest (1904–1983), professor of neurology at Columbia University, introduced me to neuroscience, letting me work in his laboratory for six months in 1955–56, at the beginning of my senior year in medical school. (From Eric Kandel’s personal collection.)

By the time Grundfest had finished his training with Gasser, he combined a broad biological outlook with a solid grounding in electrical engineering. Moreover, he had gained a good grasp of the comparative biology of the nervous system in animals ranging from simple invertebrates (crayfish, lobsters, squid, and the like) to mammals. Few people at the time had a comparable background. As a result, Grundfest was recruited back to his alma mater in 1945 to head the new neurophysiology laboratory at the Neurological Institute of the College of Physicians and Surgeons. Soon after his arrival, he began an important collaboration with David Nachmansohn, a well-known biochemist. Together, they studied the biochemical changes associated with nerve cell signaling. Grundfest’s future seemed assured, but his career soon ran into trouble.

In 1953 Grundfest was summoned to testify before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy. During World War II, Grundfest, an outspoken radical, had worked on wound healing and nerve regeneration in the Climatic Research Unit of the Signal Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. McCarthy implied that Grundfest had been a Communist sympathizer and that he or his friends had conveyed technical knowledge to the Soviet Union during the war. At the McCarthy hearings, Grundfest testified that he was not a Communist. Invoking his rights under the Fifth Amendment, he refused to discuss his own political views further or to discuss those of his colleagues.

Not a shred of evidence was ever produced by McCarthy to support his allegations. Nevertheless, Grundfest lost his funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for a number of years. Nachmansohn, fearing that his own governmental funding might be compromised, shut Grundfest out of their shared laboratory and broke off their collaboration. Grundfest had to reduce his research group to two persons, and his career would have been damaged even more severely had it not been for the strong support he received from the academic leadership at Columbia.

For Grundfest, the reduction of his research capability at what proved to be the peak of his scientific career was devastating. Paradoxically, the circumstances proved beneficial for me. Grundfest had more time available than he otherwise would have, and he devoted a substantial amount of it to teaching me what brain science was actually about and how it was soon to be transformed from a descriptive and unstructured field into a coherent discipline based on cell biology. I knew next to nothing about modern cell biology, yet the new direction in brain research, as outlined by Grundfest, fascinated me and stirred my imagination. The mysteries of brain function were beginning to unravel as a result of examining the brain one cell at a time.

AFTER BUILDING THE CLAY MODEL IN MY NEUROANATOMY

course, I thought of the brain as an organ apart, one that functions in ways radically different from other parts of the body. This is true, of course: the kidney and the liver cannot receive and process the stimuli that impinge on our sensory organs, nor can their cells store and recall memory or give rise to conscious thought. However, as Grundfest pointed out, all cells share a number of common features. In 1839, the anatomists Mattias Jakob Schleiden and Theodor Schwann formulated the cell theory, which holds that all living entities, from the simplest plants to complex human beings, are made up of the same basic units called cells. Although the cells of different plants and animals differ importantly in detail, they all share a number of common features.

As Grundfest explained, every cell in a multicellular organism is surrounded by an oily membrane that separates it from other cells and from the extracellular fluid that bathes all cells. The cell surface membrane is permeable to certain substances, thereby allowing an exchange of nutrients and gases to take place between the interior of the cell and the fluid surrounding it. Inside the cell is the nucleus, which has a membrane of its own and is surrounded by an intracellular fluid called the cytoplasm. The nucleus contains the chromosomes, long thin structures made of DNA that carry genes like beads on a string. In addition to controlling the cell’s ability to reproduce itself, genes tell the cell what proteins to make to carry out its activities. The actual machinery for making proteins is located in the cytoplasm. Seen from this shared perspective, the cell is the fundamental unit of life, the structural and functional basis of all tissues and organs in all animals and plants.

Besides their common biological features, all cells have specialized functions. Liver cells, for instance, carry out digestive activities, while brain cells have particular ways of processing information and communicating with one another. These interactions allow nerve cells in the brain to form complete circuits that carry and transform information. Specialized functions, Grundfest emphasized, make a liver cell uniquely suited to metabolism and a brain cell uniquely suited to processing information.

All of this knowledge I had encountered in my basic science courses at New York University and in the assigned textbook readings, but none of it excited my curiosity or even meant much to me until Grundfest put it into context. The nerve cell is not simply a marvelous piece of biology. It is the key to understanding how the brain works. As Grundfest’s teachings began to have an impact on me, so did his insights into psychoanalysis. I came to realize that before we could understand how the ego operates in biological terms, we needed to understand how the nerve cell operates.