In Search of the Niinja (23 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

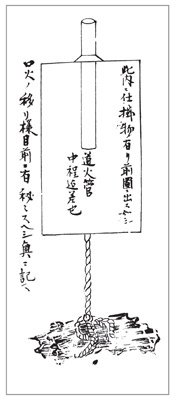

The landmine shown is similar to the ones in the ninja manuals and

Sung Ying-hsing

states that the fuse is possibly bamboo containing embers and bitumen, similar to the Japanese version. Japanese fire skill manuals show in detail sub-aquatic mines that are used to destroy enemy ships.

A Japanese version of the sub-aquatic mine.

A Chinese fire arrow.

Author and academic Joseph Needham’s extensive work catalogues the common use of rockets and incendiary projectiles and establishes their prevalent employment in Chinese warfare. The use of these weapons was well known to the ninja. The shinobi arrows closely match those of the Chinese military.

Fire arrows in the

Bansenshukai

and the

Shinobi Hiden

’

s

Youchi Tenmon Hi

exactly match the Chinese description from the

T

’

ai-pai Yin-ching

: ‘Take small gourds full of oil, affix them to the tips of arrows and shoot them onto the roof of towers and turrets.’

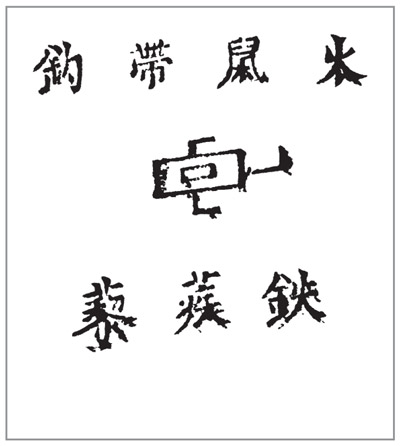

The concept of ‘fire rat’ can be found in both Chinese warfare and entertainment. A fire rat (

Huo lao shu

)

61

is a small incendiary ‘rocket’ or firecracker that jumps around the floor in a rat-like fashion. This has been used as both a weapon and a child’s toy and is still in use in China and Japan today. As a weapon, it is a small cylinder with hooks embedded in the sides and the aim is to put several in a container and throw them at the enemy, so that the fire rats shoot out and attach themselves via their hooks to enemy troops and buildings, causing fires and distractions.

In the shinobi sections of the

Gunpo Jiyoshu

manual a form of explosive hand-thrown arrow is described and illustrated. It is accompanied by an intriguing quote: ‘This should be used just as the name implies ‘

Nezumihi

, or Rat Fire’. The connection does not stop there; the ideograms themselves are identical to the Chinese and the Japanese description fits entirely with their use.

The weapon in the manual may be the container that housed these fire rats, as stated in the Chinese manuals, or a larger single fire rat. The latter is probably more likely as the conical end of the weapon is not designed to penetrate (like others in the manual) but would aid a spinning motion. It has to be imagined that a good quantity of these were thrown during a night attack.

A Chinese fire rat.

The

Shoninki

adds to its instruction on tools for carrying embers the statement ‘This [tool] is also good for

Jiyaki

.’ The meaning of

Jiyaki

when literally translated is ‘ground burning’ and is relatively difficult to find in Japanese.

Jiyaki

is burning the ground around an army, paying attention to the wind, making use of dry grassy areas. The counter to this was to identify areas which would be open to

Jiyaki

attacks and pre-burn them, or if a

Jiyaki

attack was initiated, then to set a fire behind the troops to allow for open ground to form before the enemy fire reached your own troops – a dangerous gamble. Remembering that this was only done in dry seasons and on massive scales, it would only take the wind to shift or a miscalculation for utter disaster to hit. The

Ts

’

ao-lu Ching-Lueh

shows how to defend against this ground burning skill: ‘Should you happen to encounter fire, cut down grass and reeds to the side of the army and in accordance with the wind, burn them in advance [of the approaching fire].’

The Japanese larger fire rat.

All of these examples show without doubt that there is a shared understanding of espionage methods between Japan and China. All of the Chinese references predate the ninja, some by a considerable amount of time, showing that China influenced Japan, not only in literature, art, architecture and religion, but also warfare and as a part of that warfare, the secret agent. What we cannot know is how that information came to Japan, whether carried by trained combatants or tacticians who took it over and taught the skills to the Japanese, or through literature. It is most likely that the Chinese information came gradually to Japanese shores in various forms, where it was adapted to create the ninja, a Japanese product in its own right.

Notes

49

Often read as

Yutei,

but which is phonetically spelled out as

shinobi

here, however, it appears that the author simply copied a Chinese encyclopaedia and substituted the word

shinobi no mono

to suit a Japanese audience. This means that the two may not be directly linked and that the author was explaining what this Chinese word would be translated to in Japanese, or alternatively, it could be that

shinobi no mono

is the correct reading for this ideogram in Japanese.

50

One possible reading.

51

The term

Gotonpo

has become a popular word in the modern ninjutsu community, however, it has not been found in any historical ninja manual to date and was introduced to the Japanese popular culture via this encyclopaedia. It is evident from this document that these are not practical ways of hiding as they are based on magic and are Chinese folklore. Also, it must be understood that the author had no actual training in or knowledge of ninjutsu, he simply translates a Chinese document and overlays the Japanese word

Shinobi no mono

and attributes these magical skills to the Japanese ninja. This makes this skill of

Gotonpo

dubious as, at present, it has no direct reference to an actual ninja manual and unless an example can be found, it must be concluded that this skill set was inserted into ninja history without documentation.

52

At this point the quote from the Chinese manual ends and the Japanese commentator continues.

53

It is worth noting here that some Japanese researchers attempt to show a wholly Japanese origin to the ninja and that China played no part in their development. These researchers tend to come from the post-Chinese invasion and World War II generation and naturally are prejudiced against any form of Chinese connection. On the whole, the evidence points to a mainland origin of the skills of the ninja.

54

The original radical was moon.

55

In the

Bansenshukai

one anecdote was a story of vengeance whilst the other shows the primary aim was the death of the lord.

56

A form of segregation in a battlefield camp.

57

An alternative version of this appears in the

Gunpo Jiyoshu

.

58

The context shows that this is a human and not an animal.

59

This section is possibly one of the closest Chinese examples of a ninja-like figure.

60

The example given is that of a sparrow.

61

According to Needham.

Unknown Ninja Skills

Do not fire guns from your castle at night because the birds will take flight and a shinobi will get in.

62

Medieval War Poem

T

he Historical Ninjutsu Research Team have, whilst investigating and translating historical manuals, come across various skills that were not within the general public understanding of the ninja. The following selections are examples of ninja skills that are not fully represented in the manuals or are only mentioned in passing, with little or no explanation or in an indirect manner.

The ninja spy concentrated on imitating the lesser roles in life. Many people consider that there are a limited number of disguises for the ninja; examples like the

Shoninki

’

s

‘Seven Disguises’ help promote this idea. However, nearly all ninja manuals that deal with this spying element say these disguises are not fixed and are in fact only a guideline. A shinobi would take on the guise of a trader, a (low ranking) samurai, a street performer, a servant, a beggar, a pilgrim, any form of monk or priest, or any other required masquerade. He would adopt the guise of someone of a low level and normally someone who would have a reason for travelling. We often forget that in a bustling city of maybe tens or even hundreds of thousands of people, a shinobi would be hard to find amongst all the beggars and travellers.

A ninja must know the job and background of anyone he wishes to emulate, if he is a fortune teller, he must be able to tell people’s fortunes in the way people expect, or if a monk, he must have a solid knowledge, including a temple to support his claims.

The ‘Five Types of Spy’ from the

Shoninki

were discussed earlier, however, they should be reiterated here to reinforce the idea that ninjutsu was highly involved in the area of undercover espionage. To show further examples (out of the many) the

Koka Ryu Densho

lists the following selections:

The Five Types of Practical

63

Training [Required For Infiltration in

Koka Ryu Ninjutsu

]

1 Of Gods and of Buddhism [and all required sections religious training]

2 Medicinal Training

64

3 Craftsmanship and the Arts of the Merchant

4 Sake Manufacture and Farming

65

5 The ‘Arts’ [including, dance, theatre, street performance]

The Seven Forms of Infiltration

66

1 Through Temples and Shrines

2 As a Medicine Peddler

3 As a Craftsman or Merchant

4 As a Sake [merchant or] Farmer

5 Through exploiting the Arts and Performance

6 [Damaged Text]

7 Through Greed or Desire

The above systems and selections are mainly what we would consider ‘short term’ spying but we do in fact find a selection of ‘long term’ spies in use. What is often overlooked is the idea of ‘sleeper agents’ within the enemy, from low-level serving maids used for collecting information and opening doors and locks when required, to traders that have been established for many years with shops and clientele or even ‘hermit samurai’ who live on the outskirts of a town but are known to the townsfolk. It is these long-term established spies who act as a network to be used by the ninja. Information about this network is scarce and hard to come by and it is only identified through subtle hints given in various texts. The

Bansenshukai

is one of the only manuals (to date) to talk of this network directly and advises that people should be sent out years in advance to set up such positions and to wait for times of war. The

Shoninki

also talks of visiting shinobi in the area you infiltrate. A few manuals talk of getting to a form of safe house when you get to an area and meeting up with the ‘correct people’ when you arrive at your destination. This network of shinobi appears not to be bound by political shifts, it seems that shinobi of opposing sides would or could interact. We must remember that the ninja of Iga and Koka were considered the best of Japan and they were sent all over the country to serve various lords. This fact automatically creates a network of people who have shared blood relations. The people of this loose network would know of other groups or people that any ninja might need to visit, creating a larger and integrated spy network, albeit without a central command. Spying is the foundation skill of the shinobi, which all the other skills rest on.

67