In Search of the Niinja (20 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

In China, the art of the thief appears to be separate from the art of the spy and is less frequently discussed. The art of thieving is clearly considered a skill, yet it is associated with brigands and bandits (not spies) as it was in Japan – remembering that in Japan the art of the shinobi and the

Nusubito

thief were close, if not identical on occasion.

A leader of Ch’u

in China

sent out a request for anyone who was skilled in the art of theft: ‘One man in Ch’u who excelled in thieving came to see him and said to his attendants “I heard that my lord is seeking men skilled in the Way, I am a thief who would like to offer my skill as one of your followers.”’ The leader from Ch’u sent this thief to the enemy army of Ch’i

,

who were camped close by. The first night the thief stole the general’s war curtain,

56

which was taken to the Ch’u side the next morning. On the second night, the thief took the general’s pillow. On the third night the thief stole the general’s hair pin. As a result of this the general of the army of Ch’i broke camp and left, saying that if he stayed a third night, then it would be his head that was stolen. The general’s ministers ask why he shows the thief such respect, hinting at a difference in understanding of the relative standing of the arts of thieving and spying.

According to Sawyer in his extensive work on the Chinese classics, some ancient Chinese considered a man who could sneak into a complex unnoticed, a ‘Dog-thief’. This is a small but invaluable piece of evidence. The Japanese

Gokuhi Gunpo Hidensho

manual discusses ‘Dogs’ in terms of defence against intruders and states:

How to know if a ‘Dog’ has infiltrated:

On the external side of a fence, dig a ditch three feet deep and three and a half meters wide, then place a layer of sand at the base, which measures around eight centimetres in depth. Do this so you can see the footprints of any ‘Dog’ which infiltrates [your position]. Remember, ‘Dogs’ are clever and they will hide their footprints, therefore you should neatly rake the sand into patterns

57

and observe [the sand] carefully.

The same manual also states: ‘In ancient China, the people there used to check ahead for ambushes by sending their Dogs to detect them.’

58

Thus in ancient China and Sengoku-period Japan, people who infiltrated your position were known as ‘Dogs’ and generally fulfilled the role of shinobi as one who creeps in. This puts the ‘Dog-thief’ in both counties and with identical skills. From the

Bansenshukai

we get confirmation that ‘Dogs’ are in fact high level performers of silent infiltration or

In-nin

: ‘At the time of the attack, send Meakashi scouts or “Dogs” to see how numerous the enemy are or if they are asleep or not.’

A section of the

Bansenshukai

dedicated to burglary talks of big ‘Dogs’, and of small ‘Dogs’, and ‘how to open the doors’.

Question: Granted, now it is understood that watchmen should be selected with special care, but can we use those who are restless and impatient for other jobs instead of watchmen?

Answer: It goes without saying that proper selection is the same for Meakashi scouts, Oinu big ‘Dogs’ and Koinu small ‘Dogs’, Fire Performers, Fire Assistants and other such jobs, but only watchmen are mentioned specially, because as watchmen remain outside and people of this world think that it is an easy job and do not select people carefully but use even cowards without due care and attention, this often ends in a catastrophe. Therefore, I have given emphasis to watchmen here.

The difference between big and small ‘Dog’ is not fully understood and could mean leader and support thief. Whilst thieves are universal, through linguistic similarities and actual usage we can see that Japanese ninja thieving arts were influenced by and descended from the earlier Chinese ‘Dog-thieves’.

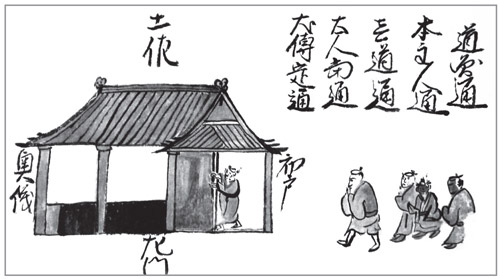

This image is taken from a ninja scroll in the private collection of Dr Nakashima Atsumi and is concerned with infiltration into a mansion. The script at the top describes the use of ‘dogs’ as infiltration agents.

A small, yet interesting connection can be seen between the

Shoninki

ninja manual and a statement from the Chinese

Kuan Tzu

. The latter states that Kuan Chung dispatches 80 people to go all over the country as merchants and sell items to people of all provinces. They do this to collate information on all the provinces and to note the wealth of those investigated, and who is ‘dissolute and discontented’. The overall aim was to identify those areas that were in a chaotic state and attack them. This actually helps identify the meaning of a skill described in the

Shoninki

. Natori describes the strategem and how to defend against it; however he does not state why the people wish to know the financial situation of others. This lack of additional information is a typical Natori trait. Through the Chinese description, we now know they were collecting information on the enemy’s economic status in preparation for an attack.

One tactic found in Natori’s writings is the idea of setting up a visit to an enemy residence and distributing gifts to the servants. At this point the ninja, having pleased the enemy, will be in a position to start probing for information. The

Ts

’

ao-lu Ching-lueh

warns against this ploy: ‘Those who provide generous gifts to your attendants want to ferret out secret plans.’ As with the previous example, this is a perfect illustration of Chinese espionage skills in the shinobi repertoire that are too specific to be a coincidence.

Manuals such as the

Shinobi Hiden

expand on collation of information, as does the Chinese

Ts

’

ao-lu Ching-lueh

: ‘When the five types of agents are employed, you must invariably assemble all the data and probe for similarities.’

The

Shinobi Hiden

and others discuss this, and recommend that when controlling agents, one must check their information individually, root out any double agents and fully investigate if one’s own spies are lying.

Ninja manuals instruct on how to find the disillusioned in an enemy camp and bring them to your side, more often then not with the promise of gold. This is reflected in the Chinese manuals:

Internal spies – Relying on those among the enemy who have lost their government positions, such as sons and grandsons of those who suffered corporal punishment and families who have been fined [excessively].

It is as important to find information on ‘stable’ people and a stable area: ‘Have our roving agents [

Yushi

] observe the enemy’s ruler and ministers, attendants and officials, noting who is worthy.’ The Six Secret Teachings says:

Ears and Eyes – Seven of. Responsible for going about everywhere, listening to what people are saying; seeing the changes; and observing the officers in all four directions and the army’s true situation.

One definite sharing of skills can be found in the form of secret letters, as a shinobi is responsible for such communication, as described by the shinobi section of the

Gunpo

Jiyoshu

manual:

Secret communication is a job that a shinobi should undertake. A secret letter should not be normally intelligible if dropped or exposed to others’ eyes. In ancient times, there was a way of writing a secret message with tangerine juice.

Both the Chinese classics and the

Bansenshukai

talk of dividing letters so that if any sections are found or intercepted the contents will not be known. The

Bansenshukai

states:

The written secret agreement should be cut into three so three people can keep it separately and it will make sense only when the general and the ninja combine it together, this is because the characters are divided, further details to be orally transmitted.

The Six Secret Teachings

states:

The letters are composed in one unit, then divided. They are sent out in three parts with only one person knowing [the full] contents.

Secret Signals Officers – Three of; Responsible for the pennants and drums, for clearly signalling to the eyes and ears; for creating deceptive signs and seals and for issuing false designations and orders; and for stealthily and hastily moving back and forth, going in and out like sprits and ghosts.

59

The

Ping-fa pai-yen

states: ‘Establish clandestine watchwords … an invisible writing.’ These watchwords are described in the

Bansenshukai,

which also explains their usage. They are a simple call and response, such as Mount Fuji/snow or tree/forest. They are to be changed daily and have to be easy to remember and are sometimes accompanied by physical gestures.

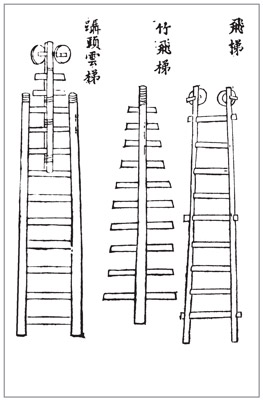

A further connection that can be identified between the two countries in the use of the Cloud Ladder . The linguistic and descriptive similarities show that China should be considered as the originator of this tool.

. The linguistic and descriptive similarities show that China should be considered as the originator of this tool.

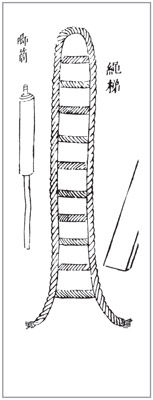

The Chinese rope ladder is identical to the version found in Japanese ninja manuals.

The Chinese versions of the Cloud and Flying Ladders. They are almost identical to the Japanese, with the addition of a wheel at the top of the Cloud Ladder.

The Cloud Ladder’s use in ninjutsu literature is also found in The Six Secret Teachings: ‘For seeing inside the walls [of the enemy] there are cloud ladders.’ The Chinese document in question then goes on to tell of a new skill, which is to observe the enemy at a distance by climbing this ladder, a tactic which could be possibly used by the shinobi. ‘In the daytime, climb the Cloud Ladders and look off into the distance.’

One further usage can be found from the same manual, for when the enemy are using

Jiyaki

or ground burning – that is to burn the grass around enemy troops – then this ladder should be used to observe what is going on in the distance, presumably above the smoke: ‘Under such circumstances use the cloud ladders and flying towers to look far out to the left and right.’