In Search of the Niinja (15 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

Chu-monomi

or middle-sized scouting groups appear to be made up of around 40–50 people out of 1000. This group were also heavily armed and prepared for engagement with the enemy.

Small Scouting Groups (

Small Scouting Groups (Ko-monomi

)

Ko-monomi

or smaller scouting groups are a small number of warriors, possibly mounted, of up to five people, most likely used to keep up to date on enemy movements from a distance. However, some scrolls which feature

Ko-monomi

skills are almost identical to shinobi activity.

Secret or Stealthy Scouting (

Secret or Stealthy Scouting (Shinobi-monomi

)

Stealthy scouting is by far the most illusive kind to pin down. There are differences in title, differences in usage between clans and also grammatical issues. On a basic level, this is a form of scouting that is done in secret and away from the eyes of the enemy, be it mounted or on foot, the latter being far more popular. Examples of secret mounted scouting can be seen in a later chapter, with the study of the

Otsubo Hon

equestrian school and their use of their shinobi skills on horseback.

According to Edo period records,

Shinobi-monomi

is also known as:

Shibami

,

Kamari,

47

Shinobi

or

Kusa

. According to the

Koyogunkan

war chronicle there were variations such as

Kamari no monomi

and they were also called

Kagi-monogiki.

The skill consists in scouting close to the enemy. This form of scouting was usually undertaken by lower class people and on foot, by men such as the

Monomi-ashigaru

or ‘foot soldier scouts’.

This suggests that lower ranking shinobi who held the status of

Ashigaru

were employed to undertake the position of overnight watchmen, lying in the grass watching the enemy, whilst the higher ranking shinobi considered such work

infra dignitatis

; however, this is merely speculation. One interesting anecdote that helps support this theory comes from the

Hojo

Godaiki

document, which states that when a mounted warrior came to take up his position in the daytime, where a low class night watchman was situated, the night-time agent attacked and tried to kill the mounted warrior in anger.

In the Japanese language an adjective comes before the subject. So in

Shinobi

-

monomi

the adjective is

shinobi

and the subject is

Monomi

. The combination means a secret-scout, i.e. ‘creeping in’ whilst scouting. The reason for grammatical examination here is that whilst the term

shinobi-monomi

exists, there is also an example of the reverse found in the

Bansenshukai

;

Monomi-shinobi

. Here the adjective-subject argument shows that this is a ninja who is undertaking a scouting mission. So a

shinobi

-

monomi

is a ‘secret scout’ whilst a

Monomi-shinobi

is a ‘ninja on a scouting mission’. Anyone can be a scout but not everyone can undertake dedicated shinobi missions. There are some people who scout in secret close to the enemy and some may go a little closer than others, to the extent of joining the enemy, making them the classic ninja.

Within the greater context of samurai warfare, the

Monomi

and the shinobi are similar, both perform scouting duties but the

Monomi

from a distance, the shinobi from within or near to the enemy. Some warriors who perform close scouting skills, such as ambush troops, may cross over into the realm of the shinobi. It may be the case that a troop of scouts would have a ninja leading them as a guide. It must be remembered that shinobi are sent to find ambush troops and hidden scouts, a constant game of cat and mouse which is played out in no-man’s-land between two samurai positions.

The

Monomi

are not associated with the shinobi skills of thieving, banditry and the other ‘criminal’ elements.

Notes

47

There is a complex argument about the use of

Kamari

and

Kusa

.

Kusa

(grass) is considered an alternative to ninja, however, Fujibayashi in the

Bansenshukai

uses both

Kamari

and

shinobi

in different ways. The ‘100 ninja poems’ used the term

Kamari

alongside

shinobi

. It appears that the two jobs overlapped but were not identical.

Bandits, Thieves and Criminals

C

ertain Japanese researchers attempt to place the ninja into the criminal bracket and have history brand them as thieves, brigands and blackguards. Whilst there are cogent reasons to connect the shinobi to mere thieves, there is a more solid argument that shows that ‘ninja activity’ and ‘theft for profit’ were different sides of the same coin.

The initial step is to identify what a criminal is and how we should understand this in the context of Japanese history.

The Oxford English Dictionary

defines crime as ‘an action or omission which constitutes an offence and is punishable by law’. This means that anyone who is acting against the laws of the state he resides in is a criminal. Therefore, it is difficult to accuse the ninja of being a criminal when the definition of a ninja is someone who is hired by a clan to perform espionage duties for an army in an enemy province. A man is hired to kill someone and the same man is hired by the government to shoot and kill someone, one is murder and the other is ‘doing one’s duty’. The argument for the ninja is eqivalent. If a shinobi is hired by an army to infiltrate the enemy, he is working for the law and not against it, yet if he is hired by a lower faction from within his domain to spy against the government or another person, he is then a criminal. If hired officially by one clan and sent to spy on another clan, he is acting within the laws of his domain, yet whilst he is in enemy territory he is in fact a criminal in that domain, making him both legal and illegal and the same time. This renders the tag of ‘criminal’ redundant, as it is impossible for a shinobi to be a criminal if he is performing espionage for the ruling military elite.

Medieval Japan was not unified as today, and the enemies over the mountains were not your countrymen, they were not the same people, you did not enjoy a national bond. The samurai of the Sengoku period were constantly at war, making the ninja a legitimate entity. All historical references mention the ninja in a functional context and not in a legalistic or condemnatory way. The charge of illegal shinobi activity does not come into Japanese court systems as it is logged as

Nusubito

. The samurai themselves participated in stealth raids, all people dealt in slavery, they burnt and killed and raped and stole, all of which are illegal in our eyes but were commonplace actions in the Sengoku period.

Theft is certainly a crime, as is killing, but only if done within your own state or to an individual who is under the laws of that province. If shinobi activity is sanctioned by the ruling family, it is legal, however if it is unsanctioned and the ninja is working within his own province and stealing or killing for his own personal gain or the gain of an employer who is not the ruling family, he is a criminal. Of course a shinobi who is employed by a clan for a period may in fact undertake ninjutsu legally yet when unemployed he may use his skills to work illegally for gain.

When talking of Iga and Koka warriors in particular, it is essential to understand that these men were hired by and attached to very powerful families, linking them to the samurai class, who were in many cases land owners, and also sophisticated and culturally advanced. (The idea that Iga and Koka were backward, hidden villages with peasants working in unity against the mighty samurai is fictitious.) In short, any ninja who is hired is a fully lawful and sanctioned individual who is working for a ruling body. There are numerous warnings in ninja manuals against using the skills within the texts for theft for personal gain (which implies that the shinobi did just that!). The military documents consider the shinobi a military threat and not a criminal one. Finally, the simple fact that shinobi are hired to capture criminals dispels the ninja-criminal myth.

The

Dakko Shinobi Nomachi Ryaku Chu

ninja scroll states: ‘Shinobi and

Tozoku

[thieves] are different …

Tozoku

‘steal in’ and steal people’s belongings, whereas shinobi simply just ‘steal in’ [for various reasons].’

Interestingly, the word

Tozuku

has connotations of bands of thieves and brings images of rough gangs breaking and entering homes, much less subtle than the image of the creeping ninja in the night. The

Shoninki

states:

[The name] ninja refers to Japanese spies; they never feel hesitant about their business, they spy whether it is daytime or at night. They are the same as

Nusubito

thieves in skill, however a ninja does not steal [for profit].

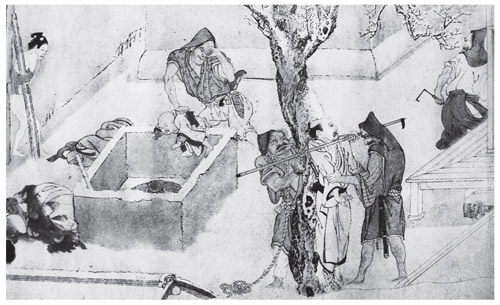

A group of

Tozoku

thieves pillaging a house. (Courtesy of Peter Brown)

Among the alternative names for the ninja, given by certain scholars you find terms like

Akuto – evil bands,

– evil bands,

Nusubito – thieves and mountain bandits

– thieves and mountain bandits and others. Often, these become interchangeable or hold the same connotations as the ninja. Of all the above, only the

and others. Often, these become interchangeable or hold the same connotations as the ninja. Of all the above, only the

Nusubito are actually listed as being akin to ninja, and this comes from the

are actually listed as being akin to ninja, and this comes from the

Shinobi-uta

, the 100 ninja poems of Yoshimori, where

Nusubito

is interchangeable with shinobi

.

48

However the others, at present have no direct connection apart from geographical location.