In Search of the Niinja (39 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

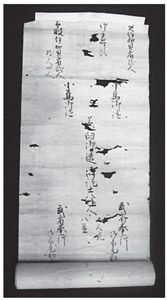

The death tablet for Natori Hyozaemon (Fujiwara Kuninori) who wrote the inscription at the back of the

Shoninki

manual.

Upon investigation, the listings for the Kishu-Tokugawa clan only have one Natori who fits the description of the author and that is Natori Sanjoro Masazumi or Natori Masazumi for short. The ideogram for

Masa

in both names is the same, so the only person to fit the bill as author of the Natori secret document was the grandmaster at that time, Natori Sanjoro Masazumi.

A version of the

Shoninki

document is found in the private collection of Dr Nakashima Atsumi, a stolen version. The inscription of 1716 in his edition reads:

The above [Shoninki] is what I copied and stole in stealth from a secret writing of the New-Kusunoki school of military warfare, therefore it is not my own work, however I will now pass it down for generations to sons and grandsons to use and practise with.

Inaba Tango no Kami

116

Michihisa, 67 years old. The tenth day of the sixth lunar month, the month of no water in the year 1716

He believes that the Natori-ryu is a new version of

Kusonoki-ryu

, the association with Kusunoki is complex but the name ‘shin-kusunoki’ was given to the school by the lord at that time. What is not known is how it was transcribed in secret. Was this man a student of the

Natori-ryu

or was he in the castle for an extended period? Natori Masatake was dead at this point and it was his son who allowed the manuscript to be stolen in such a manner.

When the history of the Kishu-Tokugawa clan was recorded, as described at the start of this chapter, the compilers were working in the early stages of the Meiji Restoration and had the opportunity to talk with and record the words of the last grandmaster of the

Natori-ryu

. That man was Yabutani Yoichiro, the apparent tenth grandmaster who was the stepson of Yabutani Yoichi, (the eighth grandmaster) and over 80 years old at the time of the interview. This shows that the

Natori-ryu

continued as a ninja school and its members were employed as such up until the end of the Edo period. What is highly interesting is that he, along with the grandmasters of the other two tactics schools of the clan, were in attendance at the second

Choshu

expedition, a battle in which the Shogunate forces, including the

Natori-ryu,

were defeated by a technically superior and modern Japanese army. Upon seeing this defeat, the grandmaster Yabutani Yoichiro reported to the compilers that he considered the old military ways to be outdated and of little use

.

He said that no one has since inherited the arts, effectively killing the

Natori-ryu

after more than 250 years of existence. This interesting episode postdates the now famous episode of a ninja who boarded Commodore Perry’s ship by over a decade, usually seen as the last ninja action. Whilst we do not know exactly what the

Natori-ryu

’

s

position was at the

Choshu

expedition, they were a shinobi school and the shinobi role in the Shogunate’

s

army is clear.

The first problem is that of of

Natori Sanjiro Masazumi being employed by the Tokugawa clan when he was just six years old after his father had died. There must be a missing grandmaster between the author of the

Shoninki

and his father. Or was the position held by Natori’s older brother until Masazumi came of age? Secondly, the record of the Kishu-Tokugawa states that the seventh grandmaster was the uncle of the fourth grandmaster, which would make him the brother of Natori Sanjuro Masazumi and over 100 years old, which leads to the probability that he was in fact the nephew and that it was a mistake in the recording. The current list of

Natori-ryu

grandmasters

117

is not is not perfect but it is the best we have to date:

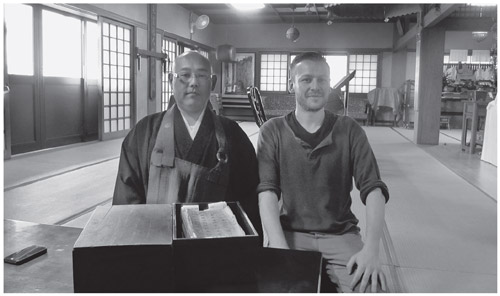

The author with Yamamoto Juho, the priest of Eiunji Temple with the local records of deaths that include Natori Masazumi’s death certificate.

1 Natori Yoichinojo Masatoshi

2 Natori Yajiemo Masatomi

3 Natori Sanjuro Masazumi (also Masatake)

4 Natori Hyozaemon Kuninori

5 Natori (Unobe) Matasaburo (adopted and given 20 Koku)

6 Ohata Kihachiro (passed it back to the Natori family)

7 Natori Nanjuro

8 Yabutani Yoichi

9 Tomiyama Umon

10 Yabutani Yoichiro

After the feudal domains were abolished, all the secret writings about the traditions of the

Natori-ryu

were dedicated to a shrine in Kii province and no one else inherited the school, bringing a Takeda (or

Shin-Kusunoki

)

shinobi school, which passed through Tokugawa hands, to an end.

One final piece of information about the lineage helps in understanding the process of inheritance within ninja schools. The inscription in the

Shoninki

states that the fourth grandmaster passed the

Shoninki

document on to Watanabe Rokurozaemon

,

which some have taken to mean

118

that the school itself was passed on to the above man. However, on inspection and with the support of the above list, it is thought that Watanabe was simply given the secrets of the art and a transcription of the

Shoninki

itself.

The

Natori-ryu

served the Takeda and then the Kishu-Tokugawa clan for hundreds of years until its demise at the Meiji Restoration. It was a military art that was based on the unorthodox and the secret; no one knows how much of the school was dedicated to the ninja arts and how much to other forms of warfare.

Notes

111

A form of defensive cape to protect against arrows.

112

In the Sengoku period the vanguard was a prestigious place and where battle hardened troops would form, as is so often the case in warfare. As the Edo period continued, the reputation of these detachments changed and in the early 1700s records start to mention their ‘uselessness’. The connotation here is that this Natori was a military man on the front lines of Sengoku period battles making him a fighting samurai.

113

Most likely at 250 Koku or more.

114

There is confusion as to whether Masazumi or Masatake is correct, as both are used historically.

115

Sometimes listed as

Fujinoissuishi

Masatake

.

116

Whilst the suffix ‘

no kami

’ is less important in the Edo period, its appearance still makes this man a samurai, adding to the growing list of samurai-shinobi evidence.

117

This list takes precedence over the now incorrect list published in the

Bugei Daijiten Ryuha

listings.

118

Myself included.

The Prowess of the Men of Iga and Koka

J

ust how renowned the men of Iga and Koka were in military Japan is shown in the following examples.

The

Sokokushi

document declares: ‘I hear that those called

Iga no Mono

are in great demand by other clans.’ The

Mikawa Gofudoki

document states:

The first time Tokugawa Ieyasu used people from Koka he had them attack a castle to put those inside into confusion and to take advantage of any gaps. As a result 70 people died, he was much impressed and chose to use them thereafter.

The Battle of Fushimi Castle in 1600 was the first action in a series of events that led to the greatest ‘internal’ conflict in Japanese history, the Battle of Sekigahara. Tokugawa Ieyasu had 60 Koka men stationed in the castle for its defence, a number which increased. The overall number of defenders in the castle was 1800 whilst the besieging army was upwards of 40,000. The castle’s defence was part of the stategy leading up to the Battle of Sekigahara. All 1800 men were expected to die and apparently they knew it. However, the castle was not succumbing to the onslaught of the western forces and its defence held out. To counter this, the besieging forces sent some

Yabumi

or secret letters in arrows to the defending men of Koka. It said that the men of Koka should set fire to their own castle so that it would fall; if they did not comply then the besiegers would execute and crucify their wives and children. To support this they had some of their families brought from Koka and made to enact a mock crucifixion. An unknown amount of

Koka no mono

gave in and set fire to the castle, however other

Koka no mono

stayed true. The castle fell and many were slain including the Koka defenders. Tokugawa Ieyasu was so impressed by the defence put up by some of the loyal Koka people that he then hired 10

Yoriki

samurai and 100

Doushin,

or displaced samurai, making 110

Koka no mono

under Tokugawa employment. These were known as the

Koka Gumi

and were led by a man named Doami, the brother of a warrior who had died in the castle. These were the same men who took it in turns with the

Iga no mono

to guard the main castle in Edo, now the imperial palace where the One Hundred Guard Hut can still be seen to this day.

The prestige of the

Iga no mono

can also be identified in documentation which is not directly concerned with them. The image shown is of a warlord’s (

Daimiyo

) parade, showing the order of his guards. The two men at the front are ‘

Iga no mono

’ and are positioned at the head. There is no explanation for their position but there is a cogent theory. The

Taiheiki

war chronicle states that men are sent ahead to wait at crossroads to guard the passing of a lord. Some gunnery and fire skills manuals explain the dangers of passing through crossroads, as can be seen in the Edo period manual shown.

Iga no Mono

parade guards. (Courtesy of Dr Nakashima Atsumi)

Crossroads. A point of danger for a lord on the move, which must be scouted.

Perhaps these

Iga no Mono

were sent ahead of the line of march to check crossroads for explosives and ambushes, as would befit their skills. They were advanced troops who helped clear the way of any threats, a suitable task considering that their history is so deeply rooted in scouting.

The following example comes from the

Keicho Kenmonshu

119

document from before 1650, which records government matters. The account pertains to the hiring of Iga men after Tokugawa Ieyasu’

s

now famous flight across Iga itself when Lord Nobunaga was assassinated, which left Ieyasu in peril. The account shows how, during Lord Nobunaga’

s

war, the social structure of Iga was falling apart:

Lo, when Lord Nobunaga was killed and Lord Ieyasu had to pass through Iga, there was a hostage offered to Lord Ieyasu [to guarantee his safety] and he was thus guarded through to where he wanted to go, which allowed Lord Ieyasu to get back home and afterwards the country came to peace. [For this] 200 people where hired and later came under Hanzo III and these [Iga] men were all Hyakso-samurai or peasant samurai. This was also the rank of Hanzo’s grandfather

120

but he had moved out of Iga and left his hometown at an earlier point and had come to the Mikawa clan, where he performed several great deeds and thus came up through the ranks [of the samurai]. But others [from Iga] stayed in their homeland, and subsequently the Iga people, those of samurai class, were devastated by Lord Nobunaga and were reduced in status down to peasants.