In Search of the Niinja (43 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

The governor Todo Takatora who governed Iga after its fall ordered a return of all

Iga no mono

from across Japan and introduced the social status of

Musokunin

, a move designed to pacify the now angry men of Iga. A

Musokunin

was neither peasant nor samurai, he had a foot in each camp. This gave the men of Iga some status back, and raised them above the peasants they once controlled, yet kept them under the new ruling samurai elite.

All the way through the Edo period, we see the use of ninja to perform duties such as capturing criminals and basic policing and spying. They were also given the label

Doushin,

which which meant they were below samurai but above peasants.

So the ninja’s skills ar no longer required, their ancestral families are displaced and they are engaged in mundane tasks. Combining these truths with the myth of the Iga peasant families and comic book stories of the ninja versus the ‘evil samurai’, the idea of the ninja ‘underdog’ took root and has left us with an incorrect version of their history.

Circulating around the ninjutsu community is the idea that ninjutsu was used by the Japanese government in the Second World War and more specifically that it was taught at the Japanese espionage and special agent training facility known as the Nakano School of War. This school taught members in guerrilla warfare and clandestine missions. The late ninja researcher, Mr Fujita Seiko, is rumoured to have taught the art of ninjutsu at the school.

The cover to the English version of Onoda’s book.

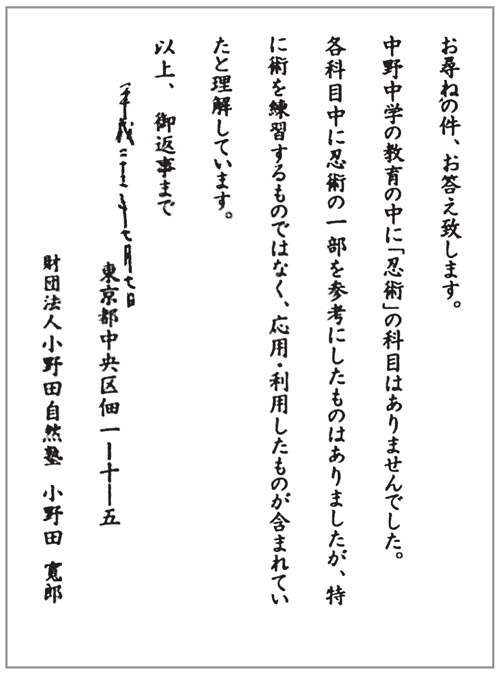

The postcard from Onoda Hiroo.

As would be expected, the Japanese are not fond of revealing their clandestine operations of World War II to the public and most veterans have now passed away. However, one pupil of the school, a highly controversial and popular figure, is the army officer Onoda Hiroo. Mr Onoda is the agent who conducted clandestine warfare in the Philippine Islands for over 30 years, continuing the war and refusing to believe that it had in fact come to an end, choosing instead to believe that this information was propaganda. In 1974, his wartime commanding officer came to order his surrender and return to Japan.

To try to pin down the story of ninjutsu at the Nakano school, I contacted Mr Onoda to ask him directly if ninjutsu was ever taught at the school. I received a brief reply with an answer that did not in fact confirm or deny the use of ninjutsu:

Dear Antony Cummins

I am writing to you to answer your questions. In the curriculum of Nakano school, there was no subject of ‘ninjutsu’. Though in some subjects, there were elements which contained [or referenced] parts of ninjutsu, it was not exactly the study of individual skills but simply had the applications [of ninjutsu]. That is my understanding.

Regards

Onoda Nature School Foundation

Onoda Hiroo

Mr Onoda states that whilst he was there, no direct teachings of ninjutsu were undertaken, yet he implies that sections of what they did learn could in fact be considered to reflect the ninja arts, leaving room for Fujita’s claims to refer to the period after Onada’s departure from the school and entry into the jungle.

Stephen C. Mercado’s well researched book,

The Shadow Warriors Of Nakano

has no mention of either ninjutsu nor Fujita Sekio and in fact mentions the ninja just once in the opening, stating that these figures were the spies of a bygone era. He does not connect them to the Nakano School. The claims of Fujita’s connection to the school and the teaching of ninjutsu are dubious. It appears that whilst sections of the curriculum had echoes of ninjutsu, it was not a skill taught to the students there.

As stated earlier, there are some records which specifically mention ninja assassinations; the attempt on the life of warlord Oda Nobunaga was one of them. However, what makes this especially amazing is the fact that the assassination attempt appears to use a secret ninja skill which is found in the

Bansenshukai

manual, the Double Shot Musket.

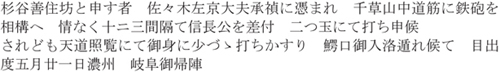

Sasaki Sakyo-dayu Jotei instructed Sugitani Zenjubou to kill Lord Nobunaga whilst he was travelling near Mount Chigusa. According to the records, the shooter was at a distance of twelve or thirteen Japanese Ken and shot ‘two bullets’. The drama was recorded in the document Shincho Koki by an attendant to Nobunaga. The Japanese quote is as follows.

The interesting section here is the use of the ideogram Futatsudama

Futatsudama

or ‘double bullet’. This has never been questioned in the Japanese historical community and is simply considered as two shots, most likely from two muskets. The main question here is, did he shoot from two separate guns or from one? To reload a musket would take far too long and Nobunaga would be well protected seconds after the first shot, so the best answer would be that he shot from two loaded weapons. However, the most likely answer is found in ninja documentation. The

Bansenshukai

sheds light on this as a ninja skill, with its instructions on the ‘Double Shot Musket’:

The Double Shot Musket

Put gunpowder and a bullet as normal into a musket. Next place wet paper [down the barrel] on top of the first bullet and then place a second charge of gunpowder down the barrel. Then, insert a bullet which is slightly smaller [than the first one] and cut a

Hinawa

fuse down to one

Sun

in length, light this fuse and put it down the barrel. When the

Hinawa

ignites the gunpowder, the outer bullet fires and then you may shoot the normal bullet as usual [giving you a second shot].

This method gives you two shots in very quick succession, allowing a single shooter that extra advantage. It is impossible to know if this was the skill used that day but it is without doubt a possibility, as the shooter and the

Bansenshukai

are both from the same area and this is an attributed shinobi skill. Unfortunately (for the shinobi) the shots did not kill Nobunaga and according to the document

Zenjubou

, the shooter was captured at a later date, buried up to his neck in sand and cut with a bamboo saw until he bled to death over time.

Notes

128

A purely modern combination of words, which never appear in Japanese history.

129

The

Iga Ueno

ninja

museum research section states ninjutsu is not a martial art, as does the Momochi Koka Ninja House/Museum and other ninja researchers such as Nakashima, Seiko, Kawakami and Otake. They consider this new line of ‘ninja arts’ as ‘entertainment’ and in no way a real line or a replication of historical ninjutsu.

130

Kendo teaches the student to hit armoured areas, not ideal in real warfare.

131

Fujibayashi here is determined to state that this ‘criminal catching’ is

not

ninjutsu and is not the role of the ninja and then complains that the shinobi are having to perform this duty more and more; a reflection of the fact that the status of the ninja was in decline at this point.

132

Research has shown that Sengoku period combat was harsh, brutal and unromantic, glorious deeds are stripped away with headhunting and murder taking their place.

The Death of the Ninja

T

his book has attempted to reconstruct the history of the ninja in the Sengoku period from their writings in the Edo period of peace. The life of an Edo period ninja was simply the life of a spy, no different to any other spy in the world. As time passed, the need for highly trained infiltration agents who could climb castle walls and burn castles to the ground had come to an end. Just as the samurai warriors became bureaucrats and public servants, the ninja had changed from elite commandos and spies to half-trained shadows of their forerunners, employed in police and spy networks. Little is known either of Sengoku period training or training in the Edo period, but there a few small glimpses.

The

Okayama-han Hokogaki

is a record of all the retainers for the Okayama domain that served the clan over the last 200 years of the Warring period. It states that during the Sengoku period there were 50 ninja who were hired by the clan and whilst in the last days of the Shogunate, just before the 1868 switch to the Meiji government, the clan had just ten hired shinobi. Associate Professor Isoda comments on this record that it shows the quality of ninja steadily declining. One ninja retired complaining of backache! The record shows that as time progressed, there were fewer accidents, suggesting that training no longer took place.

So what did happen to the ninja at the last? As the story of the above Okayama clan and the tactical failure of conventional samurai strategy in the final days of the Tokugawa government show, shinobi were still hired and retained as ninja until the first days of the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s.

The original Edo castle guards made up of

Iga no mono

under the guidance of the Hattori family faded into obscurity, but were referenced as late as 1727 in the commentary of Ogyu Sorai, in his work

Seidan

. He mentions the Iga servants and criticises their greed, the requirement to compensate them for any favours or services done within the castle. In addition to this, we know that ninja retained in Kawagoe were used to retrieve information on the Hidatakayama peasant’s rebellion in 1773 and also the 1779 rebellion of Oshi, showing that the ninja were still in use as government spies towards the end of the eighteenth century.

We have to consider the spies that were brought from the Kishu domain who were used to create the now infamous

Oniwaban,

or secret spy network of the Shogun in the early eighteenth century. They are considered to be shinobi, but without documentary evidence. Logically, the connection between the ninja and the

Oniwaban

is obvious; the

Oniwaban

were made up of spies from the Kishu-Tokugawa clan when that clan took the place of the Shogun in 1716, and at that time, the

Natori-ryu

was the clan’s secret war school. Of course, the

Natori-ryu

are famous for the

Shoninki

ninja manual, making the teachings of the

Shoninki

the most likely basis for the

Oniwaban

spy tactics. Or the spies were taken from the

Iga mono

that worked for the same clan.