In Search of the Niinja (44 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

The true history of the ninja ends after the Meiji restoration; there appear to be no more references to the ninja being retained by any factions, or by the military.

Japan has never lost its love of the ninja. Stories of the ninja continue to be told, such as those of the Sanada

Ten Braves, ten ninja heroes who had adventures in comic and story books and had fictional ninja schools

.

By the mid-twentieth century, some researchers had started mixing their research with claims to actual ninja lineages and a surge of new claimants started to appear. Their claims generally consisted of unsupported lineages that appeared to mimic comic book ninja and the demonstration of acrobatic ‘ninja’ fighting skills (such as hand springs and flips whilst distributing

shuriken

against the ‘evil samurai’ figure) and being dressed in black. There were some circus tricks, like walking on glass and nails. These ninja pretenders wrote on the subject of ninjutsu, resulting in the contamination of the historical approach and making the shinobi a taboo subject for Japanese academic research. No claimant has ever been able to supply any form of evidence that proves a lineage before the 1950s, and all of them show vast inaccuracies pertaining to the shinobi arts, making the

Natori-ryu

and the Okayama clan the last records of the use of the ninja

to date.

The ninja died out at the end of the Tokugawa period, leaving only a handful of stories and documents in some families and a small amount of information to be passed on in certain sword schools.

The Ninja Found

A

t the start of my attempt to recreate the correct history of the shinobi I had to throw off any preconceptions about what I wanted them to be and to allow myself only to concentrate on what the ninja actually were.

Various problems have arisen during this research. There is the refusal of private collectors to reveal their manuals to the public; understandably they withhold the information owing to the astronomical costs of the manuals themselves, fearful of devaluing their investments. Many private concerns, such as the Iga Ueno museum, guard their treasures fiercely, and even during a high budget documentary I was involved with, they refused to show them to the camera. With ninja treasure hordes such as these, and collectors scouring the market for ninja manuals, a great deal of the information is withheld. Luckily, there are small libraries and collections that allow access to their shinobi works and of course some of the manuals are open for public viewing, especially those which are considered the canon. The manuals actually help authenticate each other and even though the selection is limited, what is available clearly identifies a core curriculum for ninjutsu and establishes the ninja as a very real figure in military history.

It is not only our generation that fictionalised and tried to claim ninja ancestry. The Edo

period sees a rise in ninja manuals, but it also heralds an increase in fake documents and stories, which is one possible reason for some collectors or museums to keep their documents under wraps. There are also documents that include fiction yet at the same time hold truths. It is here in this middle ground where the danger for ninjutsu research lies, yet with iron bars and zealous guardians at the gates of ninja research, it will be hard to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Let us reprise what we do know for sure. The

shinobi no mono

, or ninja, was forged in the ‘Dark Ages’ of Japan and came to us as a whole concept at the end of the fourteenth century, where they appear to have some form of foundation in the ‘robber-knights’ of the century before. The origin of their skills has a clear connection with the skills of China, making the arts of ninjutsu of Chinese ancestry, yet with an unquantifiable level of identity. Were the skills brought in person by Chinese immigrants, or were they imported by Japanese travellers abroad, or did the arts of the ninja arrive in Japan from the written words found in the Chinese classics? China appears only to be a source of information and not a direct ‘teacher’. China itself has the Dog-thief, the Incendiary-thief, the Spy and the clandestine warrior armed with guerrilla warfare, all of which make up the skills of the ninja. But it is only in Japan that we see the forging of all these elements into one person. So it would appear that ninjutsu arrived piecemeal from China, where it was assembled by the Japanese and utilised by people like Yoshitune, Masashige and Shingen

.

From here it then moved to Iga and Koka, a pit of violence and bloodshed, which carved the glamorous image of the Men of Iga and Koka as experts in the arts of

shonobi no jutsu

, who were hired out across the length and breadth of Japan. They carried their clandestine skills across the armies and developed a loose spy network across Japan. The Sengoku or Warring period utilised these uniquely skilled warriors and had them engage in espionage and clandestine warfare. The romantic image of the ninja is not in itself a lie: the ninja burning castles and climbing to cliff tops, secret flute messages on the wind and hidden messages furled inside arrows; the scout in the grass and the sleeper agent in his shop, poison in a lord’s goblet and a sword thrust in the night. Add to this the more horrific images of infanticide, head-hunting, rape, sexual slavery, homosexual paedophilia, murder, theft, drugs and betrayal, and the ninja truly starts to come into focus. A far cry from the black-clad comic character, the shinobi is a spy, thief, warrior, infiltration agent, explosives and fire expert, secret scout and killer. Undercover in enemy territory, he truly deserves the fame which he has acquired. He is one of history’s greatest military assets, the

shinobi no mono

, the ninja of Japan.

From left to right: Masako (Natori) Asakawa, Yasuko (Natori) Hine , the author, Yoshio Hine, Mr Asakawa and Juho Yamamoto.

Historical Ninja Manuals

H

ere the Historical Ninjutsu Research Team has translated a selection of short ninja-related documents. This collection will help you understand the political world in which the

shinobi

lived, the tools of the trade, and the feel of the different forms and styles of the documents themselves. The following documents have been translated by Antony Cummins and Yoshie Minami.

The following story is taken from the seventeenth-century

Intoku Taiheiki

, a war chronicle which revolves around the Mori clan, and was written between 1688 and 1704.

This episode of ‘sword-theft’ reads just like sword-theft ninja test often portrayed in film. More than one historical record, written by real samurai, actually advises warriors to sleep on strings attached to swords to prevent shinobi from creeping in and stealing weapons. The

Bansenshukai

retells sword-theft tales and other ninja manuals highlight the importance of taking away the enemy’s weapons in secret and destroying them. Therefore, before we push episodes like this into the realms of legend, we must remember that the job of the ninja was theft and swords were quite a valuable asset. Therefore, whilst the sword stealing has become a cliché, it is most likely a real description of the arts of the ninja.

Sata Hikojiro, Jingoro and Konezumi or Little Mouse were three brothers who were considered to be excellent ninja (

shinobi no Jozu

) and who were formidable thieves. Because of this, the Ashigaru foot soldiers and others of the Sugihara family all studied the shinobi arts under these Sata brothers.

The Sata brothers could elude people’s eyes or fool their minds as well as foxes or raccoons can and some people say they can do it even better.

An example of their skill: several people were sitting around a sunken hearth which had lots of pieces of firewood within it, despite the fact that they all kept an eye on the firewood sticks that were there, the brothers could steal them one by one without anyone noticing it at all. Another example was shown when a man named Irie Daizo challenged the Sata brothers to take his sword that very night, as he knew they were

shinobi no Jozu

or great shinobi. Upon his request, the Sata brothers inquired if they could successfully steal the sword then would he give it to them? He assured them that he would give it to them but he warned if he could hear or notice them at all, then he would prevent them by any means he could.

Thus, Irie returned to his home and secured all the locks on the doors of every corner of the house and remained awake with his eyes open. When the Sata brothers secretly arrived at the home of Irie, they saw all the doors were guarded securely. However it is the first lesson for shinobi to open the doors or break through walls, so there was no difficulty for them to open an entranceway. After infiltrating, they secretly observed the situation and found that Irie was lying there yet he was fully awake. So one of the Sata brothers took paper from the folds of his kimono and soaked it in the water which was kept in a bucket [somewhere in the residence], and dripped drops of water, one by one onto his head. So, Irie thinking it might be a leak in the roof, raised his head up a little, and the Sata brothers took the opportunity and stole his long and short swords secretly from under his pillow and then retreated [back into the night].

Ikkan No Sho

Kusunoki Masashige was a fourteenth-century warrior. No writings contemporary to his lifetime survive, however, it was common for a system to latch on to a famous name, and it does not make the following seventeenth-century information less valuable. In fact this manual has a foreword which can be dated to the mid-1600s, which is considered old for ninja information. The passages are from different points in the original text.

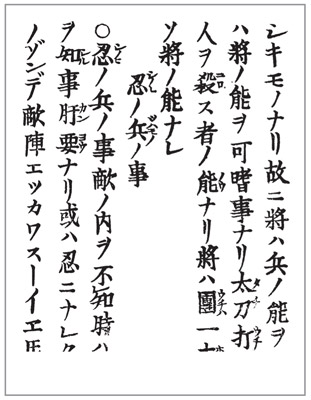

The ninja section of the

Kusunoki

military scroll.

The Art of the

Shinobi Tsuwamono

or shinobi-soldier

You need to obtain inside information on the enemy. However, experienced shinobi may lie to you, and in fact may not have even got close to the enemy and may simply talk about what is most plausible, as they are clever. Because of this, select a talented one from your men and give him enough reward [to satisfy him] and make a prisoner of his wife and children,

133

so that he will not trick you.

Also, you should send around five to seven [shinobi] to go undercover in the enemy territory and do this for either half a year or a full year before [any attack], so that you have inside information. Unless you know the inside of the enemy, your plans will not be achieved and any general should be resourceful about this issue [of using shinobi]. As even in peace times you should send shinobi to various provinces so that they can know a place and be familiar with the people’s ways, this is because this information cannot be gained instantly.

The Art of Discovering Shinobi by Speech

In order that Shinobi Tsuwamono, that is shinobi-soldiers, will not become mixed in with your troops in your castle, you should check [those who pass] everyday with passwords. Also, the language and dialects of each province

134

[in Japan] are different from each other and you should be careful of the way people talk.

When a man is leaving a castle, you should check with his master [

Sujin

] who he is and check if people have the daily passwords when they go in or out.

The Way of Castle Guards

In a position where it is hard for the enemy to attack, you should position older soldiers of the age of 40 and beyond as guards. This is done to protect against and to prevent shinobi [infiltration] and night attacks. These guards will not fall asleep and they think of everything and with care. For a place where the enemy are likely to attack from, put younger guards of under 40 years old but mix in a few older soldiers. Also, for every station and posting, you should place someone who can guard against deception .

.