In Search of the Niinja (38 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

Interestingly all three founders of each of the traditions originated from the Koshu domain, which means they were employed by the Takeda clan before the Edo period. Tokugawa Ieyasu had a great respect for the warriors of Koshu under the Takeda clan; to be a school under Takeda was a highly prestigious historical claim. It is highly likely that the Natori military arts were founded in the tradition of the Takeda clan, making the

Shoninki

a detailed historical account of Takeda ninja skills. Whilst the origins can be located in the Takeda tradition, there is also the possibility that some of the shinobi skills would have come from a Kusunoki line.

Wakayama Castle was burnt down in the Second World War and reconstructed. This is where the Natori family served the Tokugawa.

Masatoshi was the grandfather of the now famous ninja author and was a military man and samurai in the Sengoku period. Records of this Natori member are scant, however it is known that he served the Takeda clan from an unknown date until 1582/3 where his position within the Takeda clan was in the

Sakite

112

or in the vanguard, making him a front-line samurai of the Sengoku period. As his age is unknown it is difficult to determine what date he started his service, or more importantly if he served under the famous warlord Takeda Shingen himself. It is certain that this Natori served Shingen’s son Takeda Katsunori and was thus involved with the conflicts with Tokugawa Ieyasu, which led to the defeat of the Takeda clan and the death of Katsunori.

With the fall of their lord and the Takeda family, the Koshu warriors were now at the mercy of the Tokugawa war engine. Luckily, with Tokugawa Ieyasu having such a high respect for Takeda and the warriors of Koshu, he travelled to the Takeda domain to personally retain sections of the Takeda force. In 1582/3 Tokugawa met with these warriors and instructed them on their future service. We do know that Tokugawa Ieyasu spoke to and directed Natori Masatoshi on his future service to the Tokugawa family,

113

which confirms he was a samurai.

Natori was instructed to serve Yoshiwara Matabei, who was one of the

Anegawa Shichi Hon Yari

or the ‘Seven Spears of the Battle of Anegawa’, a battle where Yoshiwara Matabei earned respect with an unknown but formidable deed. It is here that information becomes limited.

The last piece of information we have is that Natori Masatoshi retired from Tokugawa service and became a

Ronin

or samurai for hire, a job he carried out in the domain of the Sanada clan. Natori died in Sanada in 1619, having never met his grandson, the author of the

Shoninki

.

For those not intimately familiar with Japanese history, it is important to realise how significant Natori’s life is when looked at from a shinobi perspective in terms of location, occupation and chronology. As we do not know his age at death or birth date, speculation will have to play a part. If Natori was 60 at the time of his final illness then that would mean he was born around 1560. If so, he grew up amidst the territorial expansions of Takeda Shingen. If born earlier, then he would have been a front line warrior at the important battles, making him a shinobi of the Takeda golden years. Even if this is not the case, he did serve Takeda’s son, which was still a time of war, making him a shinobi of the Sengoku period.

There appears to be no record of why he moved from serving as a confidant of the Tokugawa clan to becoming a

Ronin.

There could be many reasons for this move from trusted samurai to wandering mercenary. Because of what we know of ninjutsu his move to

Ronin

starts to raise questions. Natori served the Tokugawa clan in the time leading up to the famous Battle of Sekigahara, a battle at which the Sanada clan was divided. Therefore it is possible that Natori was a shinobi for the Tokugawa clan and that the Tokugawa clan had a vested interest in the actions of the Sanada clan. This respected Koshu warrior could have been working indirectly for Tokugawa Ieyasu, as a shinobi during his years as a

Ronin

in Sanada lands, though we cannot know this.

Son to the above and father to the famous Natori Masatake, Natori Yajiemo is the second grandmaster of the

Natori-ryu

and the head of the family. Whilst not much is known about his life, it is known that he was a samurai worth 250 Koku at the point he was employed by the Shogunate. Early on he served Suwa Inaba no Kami, presumably of the

Suwa

clan. His next lord was recorded simply as Kazusa Sama, but his final destination, at the level of 250 Koku, was the newly formed Kishu-Tokugawa clan, recommended to them by Matodaira Osumi No Kami Meakei Genzaimon. His position within the clan was that of

Oban

, or ‘Great Guard’. This could mean either guarding the imperial homeland or, according to Dr Turnbull, being one a group of ‘elite’ mounted troops, who could be sent anywhere the Shogun needed them at speed. The latter is more probable. All we can tell from the listings is that 308 people were in the

Oban

and they were divided into eight groups. This Natori was in

Goban,

or group number five.

Returning to Dr Turnbull’s research, a samurai of 250 Koku had some standing. According to the

Bansenshukai

, a mounted samurai, which Natori would have been at such a pay grade, would have had with him four retainers when going into battle. Natori would have ridden out with:

1 A lower ranking samurai

2 A squire for his armour

3 A squire for his spear

4 A groom

So this Natori was alive when the Kishu-Tokugawa clan was established and he served the first Kishu-Tokugawa lord, Lord Tokugawa

Yorinobu, who ruled the clan between 1619 and 1667 and would have been the lord’s grandmaster of secret military tactics. He died at an unknown age in 1648, which provides the latest possible date of birth for Natori Masatake, the author of the

Shoninki

ninja manual and other military texts.

The author of the

Shoninki

and the ninja master – officially his name is Natori Sanjuro Masazumi (hereafter known as Masatake)

114

was a fourth son. This Natori was

not

the head of the family, that privilege goes to the first son by right, therefore Natori Rokudayu (his eldest brother) was given 200 Koku as the successor and the rest of the family income was shared amongst the remaining three brothers. This left Natori Masatake with a modest income of 25 Koku

,

making him a samurai on foot. However, Natori Masatake was the head of the family military school and appears to have been a very military-orientated man. He started his service to the first Kishu-Tokugawa lord in 1654 as a

Chukoshu

or ‘page boy’. His service would have started at around the age of eleven to fifteen and he would have served either the lord or his family. We can see Natori’s abilities in his acceleration through the ranks. Whilst it is believed his income did not increase, his positions were of some military importance to the Kishu-Tokugawa family. After his role as page, he became a

Goshoinban

or ‘Defender of the Writing Room’, which appears to have been the duty of protecting the inner confines of the castle. From here, Natori became a

Gokinjusume

, which translates as ‘a close and permanent retainer’. Whilst it is unknown what this entailed, the

Monumenta Nipponica

(Volume 56) explains that this could have been a position as a medical physician, which is a possibility as the Natori family are believed to have been involved with medicine and that they had a famous remedy for sword wounds and bruises. This is, however, speculation. From here, Natori’s final position was that of

Ogoban,

which, according to the eighteenth-century commentator Ogyu Sorai, is ‘The Great Guard’. What is not known is which member of the Kishu-Tokugawa family Natori guarded; it is tempting to hope he guarded the main lord of the clan.

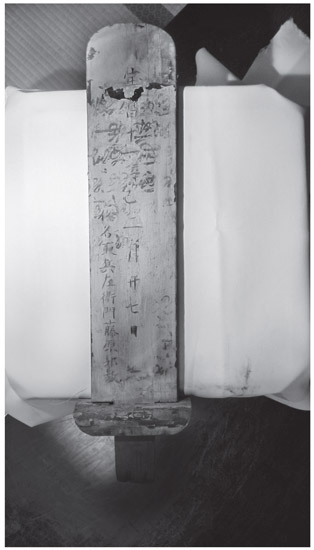

The death entry for Natori Sanjuro (Masazumi) who wrote the

Shoninki

manual. (Photo by Juho Yamamoto)

So Natori eventually became perhaps an important guard to the lord himself or the family of the Kishu-Tokugawa clan, but also the grandmaster of their secret military tactics and presumably parts of their spy network, which in the end became a part of the infamous

Oniwaba,

or

secret police. Alongside this knowledge of

shinobi no jutsu

, we know that Natori was a military strategist and author of some splendid military treatises.

If this Natori was a personal servant to the main lord he would have served three Kishu-Tokugawa lords, Tokugawa

Yorinobu, Tokugawa

Mitsusada and Tokugawa

Tsunanori. Natori retired from active service to the countryside, where he died in 1708. He probably did not serve the fourth lord, who came to power in 1705, at which point Natori will have most likely have been retired.

Natori Sanjuro Masatake’s bloodline continued with Natori Hyozaemon Kuninori, the fourth grandmaster of the Natori-ryu, with a salary of 25 Koku.

The next, Natori Shirosaburo Takanobu (?–1794) was an interesting character as he was supposed to succeed as the next grandmaster but his father requested that it go to Unobe Matasaburo. It is unknown why. What is known is that this Natori started life as his father and grandfather on 25 Koku, however he appeared to gain favour with the lord and was given the spectacular retainer of 600 Koku for some unknown reason. The position of shinobi or secret military strategist may have been two low for such a highly paid samurai. The name of his son is unknown and a gap appears in Natori Masatake’s linage, which then continues with Natori Hyozaemon Masanao, who was father to Natori Takenosuke Masakuni (?–1863) who inherited 500 Koku and adopted (Natori) Kamegusu Masakane.

One thing that this family story does prove beyond doubt is that the Natori family were samurai worth 250–500 Koku; these were no peasant ninja.

The

Shoninki,

which translates as ‘True Ninja Account’, was written in 1681 and is unsigned and does not reveal anything about the school to which it belongs, it simply states ‘Our School or Touryu’. The introduction written by the samurai Katsuda states the author is Toissuishi

115

Masatake

and records his request for a preface. However, the surname given here is not a family one and was given, as sometimes was the case in old Japan, as a salute to the nature of the author, making it more of a title than a name. The suffix of which is

which is

Shi

here means ‘educated one’ and denotes accomplishment. This leaves only the first name, Masatake. The manual was passed down in the clan and came to the samurai Natori Hyozaemon, who in his inscription passes a copy to a man named Watanabe in 1743.