In Search of the Niinja (36 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

Many people hold the misconception that ninja manuals are written in code, with the encryption passed on by word of mouth. This is incorrect with the exception of a few examples, such as the ingredients for some explosives. Most manuals have explanatory details with some further skills to be passed on by mouth, or a list of skills used as mnemonics for practising ninja.

The only real contender for the full oral transmission of tradition comes from the

Ogiden

manual, one of the oldest in existence (1586):

Of Heart and Mind:

Do not forget; Righteousness, Fidelity and Loyalty and remember, only through prayer will you achieve the truly wondrous.

Of the Body:

The conduct of

shinobi no jutsu

is found in the seven âways

109

and they are what you should know.

These next five sentences are word of mouth secrets:

Of army conduct or ways

The scroll of In (Yin) and of tools

The scroll of the army at night

The scroll of the ways of the shinobi

The scroll of water and fire

These five âscrolls' above are not passed down in writing but only by

Kuden

which is by word of mouth.

[Omitted text]

Written on the seventh day of the eleventh lunar month in 1586 by the descendant of Koka Saburo Kaneie, Mochizuki Shigeie.

In the main, a ninja manual is informative, with little hidden meaning or secret subtext. Anything that is considered too secret to write down is marked with the above ideogram and labelled

Kuden

. Sometimes ninja scrolls are comprised of a list of skills or tools where only the titles are present. This gives the illusion of code, however this may not be so, what each title meant may have been general knowledge to anyone who had been involved in military action. Simply because we no longer understand the names does not make them a secret at the time. Writing the word

Kuden

next to some points probably makes the ones without the word attached general knowledge, or at least understood to the people of the school. Some elements would only be understood by the school themselves, thus a list of skills would be written and anyone of that school would have understood its meaning; some may have had deeper

Kuden

teachings on finer points.

With these above points understood, ninjutsu can be broken down into three basic kinds of secrecy:

1Â Â Skills and information that are known by most people who have taken part in military operations and who have dealt with a shinobi or are in fact shinobi

themselves. Skill sets such as scouting and information retrieval, measurement skills and elements that are observable by the entire army.

2Â Â Skills the effects of which are understood by all, such as explosives and night raiding techniques but where the precise details are not commonly understood, thus the way of the skills (and not the outcome) are

Kuden

and are only known by a select number.

3Â Â Those elements which are deep secrets and only passed between a few members and down through the schools. Those who are subject to their effects are unaware of their application, such as a shinobi listening to conversations from within an enemy castle and without detection, infiltrating spies and sleeper agents and never having them revealed to the enemy, or magical elements retained for higher students.

Ninjutsu was not in itself a secret, as simply paying a local inhabitant for information was considered ninjutsu, as was sending a man to look at the banners of an army, these are both forms of ninjutsu and are not secret. The deeper into ninjutsu a person went, the more concealed the details of the art were. Ninjutsu is a series of levels with no strictly defined boundaries, becoming more and more secret as one gets closer to the head of the school. Some tricks were known by many but the closer you get to the head of a system then the closer to the deeper secrets you were. This might mean sharing a school's deepest secrets with only one person. But ninjutsu was not alaways only given to one individual a generation; men of Iga were hired to teach others the arts of the ninja across most Japanese armies and up to 50 ninja were hired by each domain, which would make hundreds if not thousands of schools a requirement to fill the needs of the country if only one man per generation held the knowledge, an absurdity. Both the

Shinobi Hiden

and the

Shoninki

talk of sharing the deepest secrets with only a single person, and this does not have to mean between family members, but should be with those who are most suitable for the job.

Kuden

did not refer to to the ninja alone, even the art of acting held deep secrets that were considered fit to be divulged only to a single person in each generation. The

Ogiden

ninja manual states:

If you have children or grandchildren who are not able enough or of the correct mind, then they should not use these traditions [of ninjutsu] and also, the arts should be kept secret and only given to one person [in full].

The

Shoninki

ninja manual states:

This Shoninki is the pure and supreme secret of the shinobi arts of this, our school. Though since the time of our old and previous master, this book and the arts written within has been inherited exclusively by none but only one person and now upon the request of my son [or apprentice] I hereby give all of this, in its entirety, to you. You should master it gracefully with due respect and never show it to anybody!

Seiryuken Natori Hyozaemon, 1743

The

Fushikaden

âacting manual' translated by William Scot Wilson, states:

This separate oral teaching concerning our art is extraordinarily important to our clan, and should be conferred to only one person every generation. It should not be given to someone without talent, even if he is your child. As the saying goes, âa birthright is not the clan. The clan is the handing down of the arts.'

Zeami, 1418

We do not find whole schools passed on in secret or whole schools based on oral tradition alone (with the exception of the comments of the

Ogiden

mentioned previously), but elements of the inner mechanisms are only passed on to one person per generation. Only a small percentage of a school's curriculum was secret to its members.

The

Fushikaden

manual quoted above is passed over by most students of ninjutsu. The manual itself has no connection to the ninja, it is a manual on the art of

Dengaku

acting, which became Japanese

Noh

theatre.

Dengaku

and travelling acting arts were practised by the ninja and they would use these skills to travel the country incognito and to perform in towns and villages, recording information as they went. This manual is actually an acting school of Iga, the âcentre' of

ninjutsu

and gives us a direct window into the world of the acting skills used by the men of Iga when they toured the country in disguise. Furthermore, the manual's author is thought by some scholars to be connected to both the Ueshima and Hattori clans of Iga and that there is a distant relationship to the famous Kusunoki family, all of whom are connected to ninjutsu; though no direct connection between the author and ninjutsu can be made.

Overall,

Kuden

appears in most of Japanese culture, is a massive part of ninjutsu and is also the reason for the loss of some of the finer points of the art, as all lines have died out and we no longer have a living oral tradition with a verifiable background.

110

For a western reader, the best advice is to view

Kuden

as oral transmission which may hold a secret, or it simply indicates something too complex to write down.

Notes

109

The original word in the text can be used as the name of a temple or for beggars. By its contexthere, it appears to mean âways'.

110

The

Tenshin Katori Shinto Ryu

still holds an oral tradition of ninjutsu, which is not considered a school of ninjutsu, simply a collection of knowledge to help defend against shinobi attacks.

The Famous Ninja Families of Hattori and Natori

T

he next step is to take a brief look into the history of two of Japan’s most famous ninja families. Neither should be seen as

primus inter pares,

better than other families. It is just that their their manuals survived.

One name that is always used next to the word ninja is Hattori; in plays, films and games, Hattori, or in particular Hattori Hanzo, is associated with the ninja. This has led to some strain in the academic and modern ninjutsu community, as some take for granted the connection, whilst others state that the Hattori family has no connection to the shinobi. However, actual investigation is seldom undertaken.

The germane document is the

Shinobi-hiden,

also

commonly known as the

Ninpiden

ninja manual, written by an author who called himself Hattori Hanzo. The original manual is missing and that the oldest copy is an early eighteenth-century transcription. It must be pointed out at this stage that the

Shinobi Hiden

is considered by this research team to be a collection of four separate ninja documents penned by various authors, one of whom is probably the father of the famous Hattori Hanzo II or Devil-Hanzo. It can be argued that Hattori Hanzo II, or Devil-Hanzo as he is known, was socially too elevated to be shinobi as he was a tactical commander and that his name was attached to the

Shinobi Hiden

manual to give it credibility. However, Hattori Hanzo II was the son of a hired

Iga no mono

, Hattori Hanzo I,

who was retained in Mikawa province. The social position of this retainer was in all likelihood not that high, and his father’s station in Mikawa was in all probability lower than the leading member of the Iga Hattori branch from where they originally came. The Iga branch members of the Hattori family were an elite and had an hereditary heir in Iga, making the father of the famous Hattori Hanzo lower in the chain, which could be a possible reason for his employment outside of Iga. This would exclude the now famous Hattori Hanzo II from the upper echelons. It appears that Devil-Hanzo made his mark in the world through a mixture of social poistion and his actions, swiftly taking him up the ladder in the Tokugawa forces. So those arguing against Hanzo as a shinobi are forgetting that his father was a man of Iga and that the Hattori branch from Iga was heavily involved with ninjutsu; and that by tradition he would have assumed his father’s role as a retainer. The

Hattori Hanzo

Shoyou Yari Onikirimaru Zu

document claims that Hattori Hanzo II was given his ‘Demon Killing Spear’ as a result of his achievements at Udo Castle, where he is said to have led a large group of shinobi on a night infiltration mission at the age of sixteen.

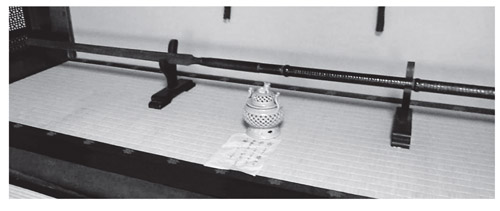

The original Demon Killing Spear of Hattori Hanzo, now located in Shinjuku Japan.

There are contradictions in this document, such as some clashes of dates. At the supposed time of the attack, Tokugawa Ieyasu was imprisoned and could not have given the spear to Hattori. Therefore, it is assumed that the raid was later than stated, making Hattori older than sixteen. However, the fact still stands that Hattori was given this spear for his achievements and that the Edo period document considers that his job was to lead shinobi in night raids. Hanzo was the person who organised Ieyasu’s escape through Iga with the help of

Iga no mono

and the Hattori Family. Because of this, Hattori Hanzo II was given the command (not ownership) of 200 Iga men, who were retained by Ieyasu, the Shogun.

In short, Hattori is the son of a man hired from Iga in the Sengoku period, which is a position normally associated with the ninja, he is from one of the Iga families who were heavily associated with ninjutsu, he led ninja in war, he was the leader of a band of 200 ninja and has one of the three major ninja manuals attributed to him. It is difficult therefore to see how Hattori Hanzo is not connected to the shinobi. In all probability, Hattori Hanzo was an

Iga no mono

, born in Mikawa, who was taught by his father in ninjutsu and given the

Shinobi Hiden

manual. He then distinguished himself as a good tactician and leader, bringing him promotion to commander of Iga ninja.