India: A History. Revised and Updated (41 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Mahmud, though a military genius, has few admirers in India. If the Hindu pantheon included a Satan, he would undoubtedly be that gentleman’s

avatar (incarnation). ‘Defective in external appearance’, he even looked the part. While gazing in the mirror he once complained that ‘the sight of a king should brighten the eyes of his beholders, but nature has been so capricious to me that my aspect seems the picture of misfortune.’

4

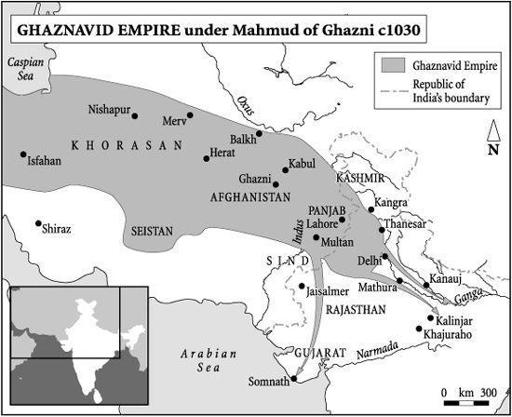

His empire, now stretching from the Caspian to the Indus, afforded a more encouraging prospect; there misfortunes could be discounted provided he could somehow consolidate it. While continuing the God-given duty of every Muslim to root out idolatry, he needed to maintain and reward his large standing army and to make of Ghazni a worthy capital, focus of loyalty and citadel of Islamic orthodoxy. These ambitions, he decided, could best be realised by trouncing his infidel neighbours and appropriating their fabled wealth. He therefore resolved on a pattern of yearly incursions designed to serve both God and Ghazni. Intent, we are told, on ‘exalting the standard of religion, widening the plain of right, illuminating the words of truth, and strengthening the power of justice’, he ‘turned his face to India’. The frontier was crossed, on what would be the first of perhaps sixteen blood-and-plunder raids, some time during the post-monsoon months of the year 1000.

Thanks to secretary al-Utbi’s contemporary account, and additional details provided by the likes of Ferishta, more is known about the Ghaznavid invasions than any other military campaign since Alexander’s. We even have a few dates. If for no other reason than that ‘it happened on Thursday the 8th of Muharram, 392 AH’ (i.e. 27 November 1001), Mahmud’s next crushing defeat of the ever-obliging Jayapala is something of a milestone; a date so precise carries conviction. The encounter took place near Peshawar in the course of Mahmud’s second invasion; and this time ‘the enemy of God’, otherwise Jayapala ‘the villainous infidel’, ‘polluted idolater’, etc., commanded a much smaller force. He still lost an unlikely fifteen thousand men and was himself taken prisoner along with many of his household. Although freed for a fifty-elephant indemnity, Jayapala acknowledged the loss of caste implicit in capture and did the noble thing. He abdicated in favour of his son Anandapala; then, like Calanus, he climbed onto his own funeral pyre.

In 1004 Mahmud was back in India. This time he crossed the Indus and, after another hotly contested battle, took the city of Bhatia (possibly on the Jhelum). He then lost most of its wealth along with his baggage when overtaken by early monsoon rains and belated enemy raids. The following year he determined to attack Multan, whose amir, though a Muslim, was now a heretical Ismaili Shi’ah. Anandapala refused Mahmud safe passage through his domains and duly felt ‘the hand of slaughter,

imprisonment, pillage, depopulation and fire’ once again. Then Multan fell, ‘heresy, rebellion and enmity were suppressed’, and Mahmud’s fame occasioned comment as far away as Egypt. In fact, al-Utbi boasted that it now ‘exceeded that of Alexander’.

The raids continued. In 1008 Anandapala suffered the Shahis’ most crushing defeat as Mahmud overran the whole of the Panjab and then took the great citadel and temple of Kangra (in Himachal Pradesh), in whose vaults had been stored the Shahis’ accumulated wealth. Here the gold ingots hauled away by Mahmud weighed 180 kilos and the silver bullion two tonnes, while the coins came to seventy million royal

dirhams

. Also included was a house, in kit form and fashioned entirely from white silver. The Ghaznavid’s appetite for dead Indians, desirable slaves and portable wealth was whetted, but not satisfied. In 1012 it carried him to Thanesar, Harsha’s original capital due north of Delhi. Anandapala, whose kingdom was now reduced to a small corner of the eastern Panjab and whose status was little better than that of a Ghaznavid feudatory, tried to intercede. He offered to buy off Mahmud with elephants, jewels and a fixed annual tribute. The offer was refused, Thanesar duly fell, and ‘the Sultan returned home with plunder that it is impossible to recount’. ‘Praise be to God, the protector of the world for the honour he bestows upon Islam and Musulmans,’ wrote al-Utbi.

In 1018 it was the turn of Mathura, a well-endowed place of pilgrimage beside the Jamuna which was sacred to Lord Krishna as well as the source of so much Gupta sculpture. Here the main temple, a colossally intricate stone structure, impressed even Mahmud. Already busy endowing Ghazni with stately mosques and madrassehs, he reckoned that to build the like of the Mathura temple would take at least two hundred years and cost a hundred million

dirhams

. According to al-Utbi, the building was simply ‘beyond description’ – though not desecration. After tonnes of gold, silver and precious stones had been prised from its images, it shared the fate of the city’s countless other shrines, being ‘burned with naptha and fire and levelled with the ground’.

Kanauj itself was then sacked as Mahmud at last reached the Ganga. The Pratihara ruler seems to have left his capital, with its ‘seven forts and ten thousand temples’, almost undefended. Evidently the reputation of the uncompromising Ghaznavid and his bloodthirsty zealots now preceded them. Al-Utbi quotes a letter written by ‘Bhimpal’, possibly the son of the Pratihara leader, to one of his father’s less defeatist feudatories which sums up Indian consternation at this new form of total warfare. It also betrays Bhimpal’s ambivalence about offering resistance.

Sultan Mahmud is not like the rulers of Hind … it is obviously advisable to seek safety from such a person for armies flee from the very name of him and his father. I regard his bridle as much stronger than yours for he never contents himself with one blow of the sword, nor does his army content itself with one hill out of a whole range. If therefore you design to contend with him, you will suffer; but do as you like – you know best.

5

From this campaign Mahmud returned with booty valued at twenty million

dirhams

, fifty-three thousand slaves and 350 elephants. There followed expeditions even further afield into what is now Madhya Pradesh to chastise the Chandela rajputs. These look to have been less rewarding, but in 1025 he targeted Somnath, another templecity and place of pilgrimage. To reach this sacred site on the shore of the Saurashtra peninsula meant crossing the ‘empty quarter’ of Rajasthan from Multan to Jaisalmer and then penetrating deep into Gujarat. It was new territory, and this was his most ambitious raid. But, taking only cavalry and camels, Mahmud swept across the desert, thereby taking his would-be enemies by surprise, and reached the Saurashtra coast with scarcely a victory to record.

Somnath’s fort looked more formidable. It seems, though, to have been defended not by troops but by its enormous complement of brahmans and hordes of devotees. Ill-armed, they placed their trust in blind aggression and the intercession of the temple’s celebrated

lingam

(the phallic icon of Lord Shiva). With ladders and ropes Mahmud’s disciplined professionals scaled the walls and went about their business. Such was the resultant carnage that even the Muslim chroniclers betray a hint of unease. What one of them calls ‘the dreadful slaughter’ outside the temple was yet worse.

Band after band of the defenders entered the temple of Somnath, and with their hands clasped round their necks, wept and passionately entreated him [the Shiva

lingam

]. Then again they issued forth until they were slain and but few were left alive … The number of the dead exceeded fifty thousand.

6

Additionally twenty million

dirhams

-worth of gold, silver and gems was looted from the temple. But what rankled even more than the loot and the appalling death-toll was the satisfaction which Mahmud took in destroying the great gilded

lingam

. After stripping it of its gold, he personally laid into it with his ‘sword’ – which must have been more like a sledgehammer. The bits were then sent back to Ghazni and incorporated into the steps of its new Jami Masjid (Friday Mosque), there to be humiliatingly trampled and perpetually defiled by the feet of the Muslim faithful.

With this supreme gesture of devotion – or sacrilege – Mahmud’s career soared to its zenith. He made one more Indian expedition, an amphibious assault into southern Sind, but died in 1030. He would not be forgotten. ‘Mahmud was a king who conferred happiness upon the world and reflected glory on the Mohammedan religion,’ declaims Ferishta. The historian goes on to admit that he was sometimes accused of ‘the sordid vice of avarice’, but concludes that this was all in a noble cause; for ‘no king ever had more learned men at his court, kept a finer army, or displayed more magnificence.’

7

The great scholar al-Biruni enjoyed his patronage; so did Firdausi, the poet, although he found it niggardly; and the Ghazni they adorned was indeed transformed into a worthy capital. Yet for Hindus, this paragon of valour and piety would ever be nothing but a monster of cruelty and iconoclasm.

Either way, the trouble with such a well-documented career is that the richness of detail may obscure the results; certainly the partisan enthusiasm

of the chroniclers leads them to gloss over setbacks. Mahmud terrorised and plundered to sensational effect, but despite all those campaigns he acquired little territory. Only the Shahi lands in the Panjab were actually retained under Ghaznavid rule. Elsewhere, and notably in Kashmir, central India and Gujarat, he made no attempt to secure his conquests or even to organise future tribute. In fact he seems often to have had considerable difficulty just in extricating himself. The great rajput fortresses of Gwalior and Kalinjar did not fall into his hands, although both were attacked. And attempts to employ as feudatories Indian princes who had supposedly adopted Islam often proved as short-lived as their conversions.

Mahmud’s forces, better led than those of his adversaries, and much better mounted thanks to their access to central Asian bloodstock, enjoyed a definite tactical superiority. They were also powerfully motivated by religious zeal, plus the prospect of booty and women in this world or something equally agreeable in the next. The Indian forces, on the other hand, betrayed an understandable reluctance to engage. The most they could expect from battles with these rough-riding ghazis from the wilds of central Asia was perhaps a fleeter horse and a slim chance of survival. Victory, were it ever attained, promised only reprisals; and for Hindus no particular merit attached to the massacre of

mlecchas

. In fact there is good evidence that the superior prospects on offer to the champions of Islam induced some Hindus from the north-west frontier to switch both religion and allegiance and to fight for the Ghaznavids.

One can hardly blame them. The exemplary resolve displayed by the Shahis was conspicuously absent amongst most of their fellow kings. Kalhana, whose

Rajatarangini

provides the only non-Muslim references to the period, gives an interesting illustration. In 1013 Trilochanapala, the son of Anandapala and the last of the Shahis to offer any serious resistance to Mahmud, was forced to seek safety in Kashmir territory. Hotly pursued, he took up a strong position high above a precipitous valley in the Pir Panjal, the outermost of the Himalayan ranges, whence he urged King Samgramaraja of Kashmir to come to his aid. Instead the king sent Tunga, his commander-in-chief. Originally a goatherd to whom a queen of Kashmir had taken a fancy, Tunga was an experienced warrior who thought nothing of seeing off the Ghaznavids. In fact he was so confident that he scorned the Shahi’s prudence and declined to take even elementary precautions like sending out scouts or setting night watches. Trilochanapala tried to cool his ardour. ‘Until you have become acquainted with the

Turuska

warfare,’ he told him, ‘you should post yourself on the scarp of this hill and restrain your enthusiasm with patience.’ But Tunga would have none of it. He even

crossed the river to give battle to a small Ghaznavid reconnaissance party. Then came Mahmud himself, the master tactician, ablaze with rage and in full battle array. Tunga took one look at his massed ranks and fled, his troops dispersing into the hills.

‘The Shahi, however,’ we are told, ‘was seen for some time moving about in battle.’ In what seems to have been the Shahis’ last stand, Trilochanapala was eventually dislodged and became a refugee in Kashmir. But while he dallied there, Mahmud would leave the valley alone. Samgramaraja retained his independence and, under the Lohara dynasty which he founded, Kashmir enjoyed another three centuries of Hindu rule. ‘Who would describe the greatness of Trilochanapala whom numberless enemies even could not defeat in battle?’ asks the patriotic Kalhana. Amazingly it was a Muslim, indeed one of Mahmud’s protégés, who provided the answer. To al-Biruni, the greatest scholar of his age, the Shahis owe their epitaph.

The dynasty of the Hindu Shahis is now extinct, and of the whole house there is no longer the slightest remnant in existence. We must say that, in all their grandeur, they never slackened in the ardent desire of doing that which is good and right, and that they were men of noble sentiment and bearing.

8