India: A History. Revised and Updated (45 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

11

The Triumph of the Sultans

c1180–1320

FRIENDS, RAJPUTS AND CONQUERORS

T

HE WORD ‘RAJPUT’

(

raja-putera

) simply means ‘son of a raja’. Although it therefore implied

ksatriya

status and eventually came to mean just that, someone of

ksatriya

caste, it originally had no particular ethnic or regional connotations. To those ex-feudatories of the Gurjara-Pratihara kings of Kanauj to whom the term is so freely applied, and to other Indian opponents of Islam to whom it was occasionally extended, it was probably meaningless other than as one of many hackneyed, and usually much more grandiloquent, honorifics. Not until the Mughal period did the word come to be used of a particular class or tribe and, given the prejudices of Aurangzeb’s reign, its connotation soon became decidedly pejorative: ‘Rashboots’, as they sometimes appeared in English translation, were freebooters and trouble-makers, ‘a sort of Highway men, or Tories’ according to a seven-teenth-century travelogue by the German Albert de Mandelso.

1

Always ‘gentiles’ (the contemporary designation for Hindus), they were encountered mainly in Gujarat and Rajasthan and were usually under arms, soldiering being their hereditary profession.

Colonel James Tod, who as the first British official to visit Rajasthan spent most of the 1820s exploring its political potential, formed a very different idea of the ‘Rashboots’. Not only was it his boast that ‘in a Rajpoot I always recognise a friend,’ but seemingly in a friend he always recognised a rajput. Their hospitality to one who was offering acknowledgement of their sovereignty plus protection from the then devastating attentions of the Marathas was overwhelming. Tod found rajputs all over Rajasthan; and the whole region thenceforth became, for the British, ‘Rajputana’. The word even achieved a retrospective authenticity when, in an 1829 translation of Ferishta’s history of early Islamic India, John Briggs discarded the phrase

‘Indian princes’, as rendered in Dow’s earlier version, and substituted ‘Rajpoot princes’. As Briggs freely admitted, he was ‘much indebted for the unreserved communications on all points connected with the history of Rajpootana … to my good friend Colonel Tod’.

2

Nor, according to Tod, were these ubiquitous ‘Rajpoots’ outlaws – or even Tories. They were sovereign chiefs and princes, scions of a noble race amongst whom, opined Tod, ‘we may search for the germs of the constitutions of European states’. Although perjured and persecuted during centuries of Islamic supremacy, they were in fact the native aristocracy of India, an indomitable people whose ethnic origins could be traced back to a common ancestry with the earliest tribes of Europe and whose genealogies as recorded in the

Puranas

reached back to the epics and the Vedas.

Thanks to the rajputs’ naturally generous disposition and to the assistance of their royal archivists and bards, Tod had been privileged to attempt a reconstruction of their history; and what a glorious tale it was. In his majestic

Annals and Antiquities of Rajast’han

, published in 1829, he regaled his readers with examples of a chivalry to shame Camelot and of a resolve worthy of Canute. Frequent references to the rajputs’ clan organisation and aristocratic sense of

noblesse oblige

went down especially well with an audience steeped in British history; and in the feudal structure of rajput society Tod thought he saw an exact equivalent of that which had pertained nearer to home in Anglo-Norman times. For ‘the martial system peculiar to these Rajpoot states’ invariably and specifically made vassalage and land grants contingent on military service and the provision of fighting men.

Admittedly, for the rajput knights themselves feudalism seemed less about tenurial feus and more about the interminable feuds to which they often gave rise. Rivalry between the various rajput houses was intense and disastrous.

The closest attention to their history proves beyond contradiction that they were never capable of uniting, even for their own preservation: a breath, a scurrilous stanza of a bard, has severed their closest confederacies. No national head exists amongst them … and each chief being master of his own house and followers, they are individually too weak to cause us [i.e. the British] any alarm.

3

They had, nevertheless, shown a bold front in the face of Muslim aggression. And for whatever that defiance had lacked in the way of coherence, they had amply compensated with a stalwart perseverance unequalled in the annals of mankind.

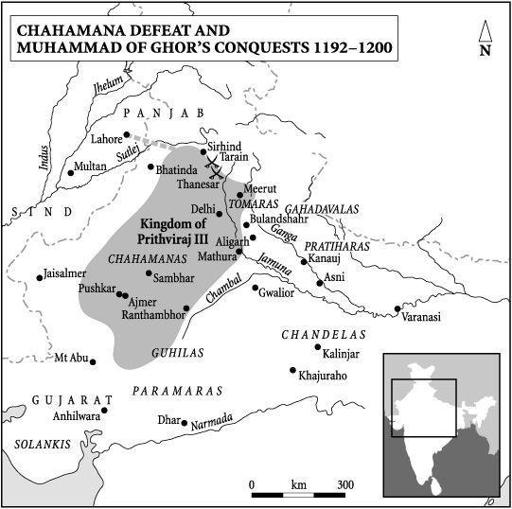

In support of this contention Tod adduced a litany of patriotic heroes

and tales of martial romance from the twelfth to eighteenth centuries. The earliest was ‘the heroic history of Pirthi-raj by Chund’, a particularly instructive saga to which he devoted considerable space. For ‘Pirthi-raj’ was otherwise Prithviraj III of the Chahamana (Chauhan) dynasty, who ruled an extensive kingdom in northern Rajasthan and the eastern Panjab from c1177. It was he therefore whose territory marched with that of the Ghaznavids at Lahore and, when that city fell to Muhammad of Ghor in 1186, it was he who stood between the Ghorid kingdom and the rest of India. Tod was wrong in imagining that the bard ‘Chund’ was a contemporary eye-witness, let alone ‘his [i.e. Prithviraj’s] friend, his herald, his ambassador’. He was therefore mistaken in taking Chand’s ‘poetical histories’ as reliable evidence. But in rehabilitating Prithviraj, as also the

ksatriya

dynasties of Rajasthan whom he had so determinedly designated as ‘Rajpoots’, Tod did both history and Indian nationalism a useful service.

The Chahamanas, like the Pratiharas and Bhoj’s Paramaras, claimed (or would eventually claim) to have acquired their

ksatriya

status from the great fire-sacrifice once held on Mount Abu. More prosaically they look to have been a desert tribe from the region around lake Sambhar, west of modern Jaipur, who over the centuries, like countless other peoples in out-of-the-way places, had undergone a long process of ‘Aryanisation’. Hemachandra Ray’s

Dynastic History of Northern India

lists no fewer than eight Chahamana families of princely standing, one of which, the Sakambhari (i.e. Sambhar) branch, remained on home ground in the vicinity of lakes Sambhar and Pushkar. Inducted into the Gurjara-Pratihara empire by marriage, they had eventually broken away and, early in the twelfth century, one King Ajaya-raja established a new capital. He called it ‘Ajaya-meru’, or Ajmer.

In the mid-twelfth century Vigraha-raja, one of Ajaya-raja’s successors, greatly extended the dynasty’s sway by pushing northwards into what is now Haryana and what remained outside Ghaznavid rule of the eastern Panjab. Delhi, too, fell to Vigraha-raja, and to record this brilliant campaign he added his own inscriptions to those of Ashoka on one of the latter’s still-standing pillars. By a strange coincidence the pillar he chose was the one, then located higher up the Jamuna, which two centuries later would be so laboriously shipped downriver for re-erection in Delhi. There, fortuitously relocated in the heart of the city to which he had laid claim, it records Vigraha-raja’s conquest of the whole region up to the Himalayas and also mentions frequent exterminations of the

mlechhas

, presumably a reference to conflicts with the declining Ghaznavids. Another inscription speaks of his having thereby made

arya-varta

‘once more the abode of the

arya

’.

Vigraha-raja died c1165. The Chahamana succession then became convoluted until Prithviraj III ascended the throne of Ajmer twelve years later. Evidently a minor at the time, he seems to have celebrated his coming of age by eloping with the daughter of the king of Kanauj. This much-loved romance is told in some detail by the unreliable Chand. On the other hand the young Lochinvar’s ambitious

digvijaya

of c1182 is shrouded in uncertainty. It seems to have brought him into conflict with, amongst others, the Chandelas and their allies and also the Solanki rajputs of Gujarat. In all such encounters he is said to have fared well and, according to another popular narrative of the period, he waxed strong enough to vow next to extirpate his

mlechha

neighbours in the Panjab.

In this he was emboldened by the decline of the Ghaznavids and the rather unimpressive showing so far made by Muhammad of Ghor. From Ghazni the Ghorid had first turned his attentions to Sind, routing the restored Ismaili ruler of Multan and eventually pushing down the Indus to Mansurah and Debal. He had thence attempted to attack the Solankis of Gujarat by crossing the Thar desert in imitation of Mahmud’s raid on Somnath. He even invited the young Prithviraj to support him in this venture. Prithviraj declined and briefly considered joining his Solanki rival to eject the

Turuskas.

But in the event this proved unnecessary, for the Ghorids were roundly defeated in Gujarat. Muhammad thereupon abandoned the idea of a trans-Thar invasion and directed his attention north-east to Lahore. Having secured that place in 1186–7, he was ready to meet Prithviraj’s challenge. Along a Panjabi frontier not dissimilar to today’s Indo–Pakistan border, ‘the Ghorid and the Chahamana now stood face to face. The Muslim knew that the wealth of the rich cities and temples in the Jamuna-Ganga valley and beyond could only be secured by the destruction of the Hindu power which held the key to the Delhi gate.’

4

Twentieth-century parallels with a situation in which Sind and Gujarat lay divided from one another by religion, and the Panjab in effect partitioned between Muslim and Hindu rulers, are hard to overlook. Pakistanis may take comfort from the fact that this division had already subsisted for nearly two hundred years in the case of the Panjab and for over four hundred in the case of Sind/Gujarat. Indians, on the other hand, take little note of the chronology and more of the outcome.

It should, though, be emphasised that during this long political stand-off there were contacts of an informal nature. Apart from commercial links, which continued much as under the Balhara’s even-handed patronage, Muslim immigrants and missionaries seem to have enjoyed the freedom of north India much as Hindus did that of Sind and the Panjab. Writing

of the Varanasi region, Ibn Asir, a contemporary scholar, insists that ‘there were Mussalmans in that country since the days of Mahmud bin Sabuktigin [i.e. Mahmud of Ghazni], who continued faithful to the law of Islam, and constant in prayer and good work.’

5

Numerous other examples of pre-Ghorid Muslim communities in India have been noticed;

6

and so has the existence of a

Turuska

tax. This could have been a levy to meet tribute demands from the Ghaznavids, but seems more probably to have been a poll-tax on Muslims resident in India and so a Hindu equivalent of the Muslim

jizya.

But perhaps the most striking evidence of pre-Ghorid Muslim communities comes from Ajmer itself. There, if later tradition is to be believed, Shaikh Muin-ud-din Chishti founded the most famous of India’s Sufi movements in the months immediately preceding Muhammad of Ghor’s assault, and so under the very nose of Prithviraj III.

To what extent religion was uppermost in the mind of either Prithviraj or Muhammad of Ghor when first they met is therefore debatable. In 1191 Muhammad took the offensive by storming a fort in the Panjab which is thought to have been either that of Sirhind near Patiala or of Bhatinda near the current Indo–Pakistan frontier. The fort was taken; but Prithviraj hastened to its rescue and, at a place called Tarain near Thanesar (about 150 kilometres north of Delhi), he was intercepted by the main Ghorid army.

The ensuing battle is described as having been decided by a personal contest between Muhammad of Ghor and Govinda-raja of Delhi, who was Prithviraj’s vassal. Govinda lost his front teeth to the Ghorid’s lance but then took fearful revenge with a spear that struck the latter’s upper arm. Barely able to keep his seat, Muhammad was saved by ‘a lion-hearted warrior, a Khalji stripling’ who leapt up behind him in the saddle and piloted him from the battlefield. Seeing this, many of Muhammad’s troops feared the worst; they believed their leader to be dead and so broke off the encounter. Had the Chahamana forces taken advantage of the situation, it might have become a rout. But Prithviraj, fresh from the ritualistic manoeuvres of a conventional

digvijaya

, mistook retreat for an admission of defeat. Ignorant of the advice once given by ‘Bhimpal’, it was as though he rejoiced over the capture of a hill and bothered not with the rest of the range. The Muslim forces were allowed to withdraw in good order. Prithviraj then ordered his army forward to a laborious siege of the Sirhind/Bhatinda fort.

Muhammad withdrew to Ghazni to convalesce and assemble more troops. The Ghorid forces included Afghans, Persians and Arabs, but the most numerous and effective contingents were of Turkic stock. Meanwhile those who had fled the field at Tarain were obliged to don their horses’ nosebags and tread the thoroughfares of Ghazni munching on grain. By mid-1192 Muhammad was back in the Panjab at the head of 120,000 horse and with an uncompromising ultimatum for the king of Ajmer: apostasise or fight. Prithviraj returned ‘a haughty answer’: he would not capitulate nor would he embrace Islam but, if Muhammad was having second thoughts, he was willing to consider a truce.