India: A History. Revised and Updated (42 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

THE TIGERS OF TANJORE

In the Hindu cycle of rebirth, death is but the prelude to life. Acts of destruction become acts of creation, as in Lord Shiva’s manifestation as

Nataraja

, ‘the Lord of the Dance’, he who whirls the world to perdition and so to regeneration. The now clichéd image of the deity pirouetting in a tangle of arms, legs and dreadlocks within a halo of flames first appears, as if on cue, in bronze figures from the Tamil country of the tenth century. Troubled times, one might suppose, heightened the popularity of both the idea and the image. Yet in the Tamil south this was not an inordinately turbulent age, more in fact of a golden age. And if one may judge by the officially inscribed panegyrics of practically any ruler since the time of Ashoka, cycles of order and disorder, of construction and destruction, expansion and retraction were constants of the Indian scene.

Dynasties died only to make way for yet more dynasties; deities were subsumed only to make room for yet more deities; and Mahmud, seemingly, ravaged only to revive. Even as he was demolishing some of the north’s greatest temples, others were being built; even as he carted away their

wealth, more was accumulating elsewhere. It was as if his labours in casting down one idol merely caused a couple more to rise up. Heracles would have sympathised. For every fifty thousand idolaters that were massacred, fifty thousand equally unregenerated devotees swarmed to some other place of pilgrimage or centre of politico-religious significance. The levelling of Mathura and Kanauj coincided precisely with the rise to architectural glory of other dynastic temple complexes. All this flatly contradicts the once popular notion that the Islamic invasions found India atrophied and supine. In fact ‘dynamic’ would seem better to describe a society so productive of soaring monuments, ambitious dynasties, dazzling wealth and buzzing devotion.

India’s largest concentration of temples, at what is now the Orissan capital of Bhuvaneshwar, were constructed over many centuries and by a succession of dynasties. Although they display a remarkably consistent style – pineapple-shaped

sikharas

with strongly horizontal vaning being particularly distinctive – some date from as early as the seventh century and others from as late as the thirteenth. But the most celebrated, amongst them the exquisite Mukteshvara, the chaste Rajarani and the colossal Lingaraja, all belong to the late tenth to late eleventh centuries. While, in the west, the temples of Mathura and Somnath were being levelled, in the east structures equally ‘beyond description’ were being gloriously erected.

In between, at Khajuraho, the ceremonial capital of the Chandelas in central India, the chronological clustering is even more notable. Of the twenty more-or-less intact temples, none is earlier than the beginning of the tenth century or later than the early twelfth. Indeed the Vishvanatha temple with its much-loved Nandi (Lord Shiva’s bull) carries an inscription of the reign of King Dhanga, who was ruling when Mahmud first invaded India. Nearby the Khandariya Mahadeva, the largest and most sculpturally elaborate of this justly famous complex, seems to have been constructed within a decade or so of the Ghaznavid assault on the Chandelas’ stronghold of Kalinjar. If temple-building was indeed ‘a political act’, there could be no more eloquent testimony to the Chandelas’ defiance of both their erstwhile Pratihara suzerains and the Muslim invader.

Later waves of iconoclasm under Muhammad of Ghor and the Delhi sultans will account for the disappearance of many other north Indian temple complexes of the tenth to twelfth centuries. Bhuvaneshwar and the other Orissan sites (Puri and Konarak) were spared only because they were sufficiently remote not to attract early Muslim attention. Khajuraho, on the other hand, looks to have survived thanks to its timely desertion by the Chandelas when the axis of their dwindling authority shifted eastwards.

Five hundred years later, when a British antiquarian, Captain Burt, stumbled upon ‘the finest aggregate number of temples congregated in one place to be met with in all India’, he found the site choked with trees and its elaborate system of lakes and watercourses overgrown and already beyond reclaim. Like Cambodia’s slightly later Angkor Wat when it was ‘discovered’ by a wide-eyed French expedition, the place had been deserted for centuries and the sacred symbolism of its elaborate topography greedily obliterated by jungle. Nor was there any local recollection of either site having ever been otherwise. Henri Mouhot at Angkor would echo, almost word for word, the surprise of Burt who, noting the then scant population of villagers who frequented Khajuraho, ‘could not help expressing a feeling of wonder at these splendid monuments of antiquity having been erected by a people who have continued to live in such a state of barbarous ignorance’.

9

The inscriptions of the Chandelas have since revealed something of that dynasty’s distinguished history, while the study of Khajuraho’s deliciously uninhibited iconography has established the importance of the site as a centre of Shaivite worship.

10

‘Barbarous ignorance’ may now be emphatically discounted. But of the rituals which Khajuraho witnessed, of its construction and maintenance, and of its economic and dynastic function, an idea can best be formed by looking at sites more comprehensively documented and less sensationally neglected. Such are to be found on or beyond the tidemark of Muslim encroachment, and most notably in the Tamil south.

By chance Mahmud’s raids into the Ganga-Jamuna Doab at the western extremity of the ancient

aryavarta

had coincided with another unexpected incursion at the eastern end of

aryavarta

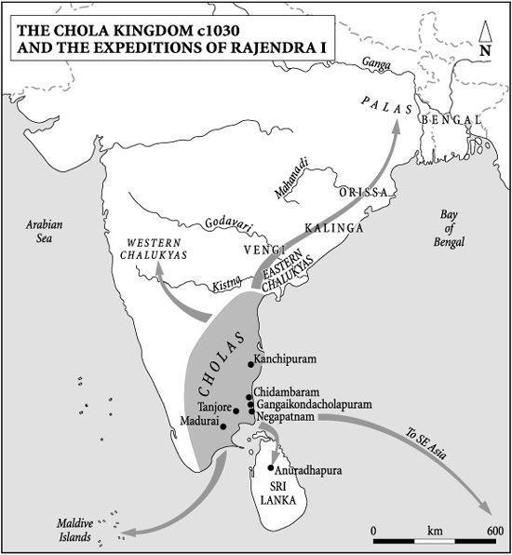

. No less adventurous, this surprise attack had originated in the extreme south of the peninsula. Far from the interminable plains of northern India and the wooded Vindhya hills where Harsha had once sought his widowed sister, beyond the Narmada river whence the Rashtrakutas had launched their challenge for ‘Imperial’ Kanauj and the bald Deccan plateau whence the Chalukyas had interminably challenged the Pallavas, below the teak forests and hill pastures of the Eastern Ghats, in a land without winter where the Kaveri river fans out into the lushest of rice-rich deltas – there, in the extreme south of Tamil Nadu, this spectacularly traditional retort to Mahmud’s iconoclasm had been mounted by the Chola king Rajendra I.

The date seems to have been about 1021, so just before Mahmud turned his attention to Somnath. Upstaging even the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan, and reversing the trend of conquest set by the Mauryas and Guptas, the Cholas were the first south Indian dynasty to intervene in the north. Nor

was this by any means the most ambitious of their foreign adventures. Turning the supposed hegemony of north India on its head, the Cholas were in fact the most successful dynasty since the Guptas. In terms of literature, architecture, sculpture and painting, theirs is an equally distinguished tradition; and thanks to it, and to their prolific output of inscriptions and copper plates, recent scholarship has constructed a uniquely detailed picture of the Chola state. It may not be entirely representative of other contemporary kingdoms; and as so often, the benefit of more evidence has generated the bane of more controversy. But here at least there are clues as to the dynamics of dynastic expansion as well as to its extent.

The Cholas, a Dravidian people first mentioned in Ashoka’s inscriptions, seem to have occupied the region of the Kaveri delta since prehistoric times. During the long Pallava supremacy over the Tamil south from the sixth to ninth centuries they figure as a tributary lineage of their more assertive northern neighbours. But as the Pallavas vainly pursued their vendettas with Chalukyan and then Rashtrakutan rivals in Karnataka and with the Pandyan kingdom of Madurai, Chola ambitions revived. A decisive battle seems to have taken place in c897 when the Chola king Aditya, having withstood a Pandyan invasion, intervened in a Pallavan succession crisis. This brought outstanding results, with the overthrow of the mighty Pallavas and the acquisition of Tondaimandalam, the Pallava heartland (around Madras) which included Kanchipuram and Mamallapuram. A subsequent victory over the Pandyas encouraged Aditya to call himself

Madurai-konda

, ‘Conqueror of Madurai’, and he is said to have lined the banks of the Kaveri with stone temples. Initially his son Parantaka improved on this

digvijaya

; but in 949 he suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Krishna III, the last of the great Rashtrakutas. Now it was the Rashtrakuta who termed himself ‘Conqueror of Kanchipuram’ and even ‘of Tanjore’, the Chola capital. For the next forty years Chola endeavours were directed towards recovering lost ground.

The classic expansion of Chola power began anew with the accession of Rajaraja I in 985. Campaigns in the south brought renewed success against the Pandyas and their ‘haughty’ Chera allies in Kerala, both of which kingdoms were now claimed as Chola feudatories. These triumphs were followed, or accompanied, by a successful invasion of Buddhist Sri Lanka in which Anuradhapura, the ancient capital, was sacked and its stupas plundered with a rapacity worthy of the great Mahmud. Later still Rajaraja is said to have conquered ‘twelve thousand old islands’, a phrase which could mean anything but is supposed to indicate the Maldives.

In the north the Cholas ran up against stiffer resistance in the shape

of a dynasty which had just overthrown the Rashtrakutas. Claiming descent from the Rashtrakutas’ original suzerains, these new overlords of the Deccan considered themselves another branch of the ubiquitous Chalukyas, once of Badami and Aihole. Usually known as the Later Western Chalukyas (of Kalyana in Karnataka), they may still be confused with that other branch, the earlier Eastern Chalukyas (of Vengi in Andhra Pradesh). But the Eastern Chalukyas now looked to the Cholas as allies and patrons; and it was while championing them, the old Eastern Chalukyas, against the new Western Chalukyas, that the Cholas became embroiled in the affairs of both Vengi and the Deccan.

In the course of perhaps several campaigns, more triumphs were recorded by the Cholas, more treasure was amassed, and more Mahmudian atrocities are imputed. According to a Western Chalukyan inscription, in the Bijapur district the Chola army behaved with exceptional brutality, slaughtering women, children and brahmans and raping girls of decent caste. Manyakheta, the old Rashtrakutan capital, was also plundered and sacked. But the Cholas did not have it all their own way, and their efforts served to make of the Western Chalukyas not obedient feudatories but inveterate enemies. The ancient rivalry between upland Karnataka and lowland Tamil Nadu, once epitomised in the struggle between the Chalukyas of Badami and the Pallavas of Kanchi, was revived as between the Cholas and the new Western Chalukyas. The old Eastern Chalukyas, on the other hand, became faithful subordinates with whom the Cholas inter-married.

These northern campaigns of the Cholas look to have been masterminded, if not conducted, by the son of Rajaraja I who would succeed as Rajendra I in 1014. As Rajaraja’s reign drew to an end he not only secured the succession but set about memorialising his remarkable achievements. This he did by constructing in Tanjore a temple. Conceived as a single entity, built within about fifteen years and little altered since, it remains the most impressive, and allegedly ‘the largest and the tallest’,

11

in all India. To many, it is also the loveliest. Additionally it hosts a veritable Domesday Book of contemporary inscriptions and a small gallery of partially obscured Chola paintings. A monumental

lingam

in the main shrine beneath the sixty-five-metre

sikhara

proclaims it as sacred to Lord Shiva, a dedication which is confirmed by its current designation of ‘Brihadesvara’ and its original title of ‘Rajarajesvara’, or ‘Rajaraja’s Lord [Shiva]’ temple. The latter name, however, makes the more important point: Tanjore’s great temple is as much about the king as his god.

Muslim writers who chronicled the successes of Mahmud were often scandalised by the hordes of celebrants, musicians, dancing-girls and servants who were attached to Indian places of worship. The five hundred brahmans and as many dancers reported at Mathura or Somnath might be taken for an exaggeration were it not clear that the Rajarajesvara in Tanjore supported a complement even larger. As well as contributing to its construction and embellishment, king, court and a variety of other military and religious donees deluged the temple with grants of land, produce, and treasure to provide for the maintenance of this retinue and for the performance of a calendar of impressive rituals. The yields of villages dotted throughout the Chola kingdom and as far away as Sri Lanka were in this way attached to the temple, which reciprocated by reinvesting some of its accumulated wealth as loans to such far-flung settlements. The temple, in other words, was like a metropolitan community which served as a centre for both the redistribution of wealth and the integration of the Chola kingdom. No less important, since the supervision of the temple’s economy was undertaken by royal officials, it also ‘provided a foothold for the kings to intervene in local affairs’.

12