India After Gandhi (131 page)

Read India After Gandhi Online

Authors: Ramachandra Guha

Tags: #History, #Asia, #General, #General Fiction

The pattern set in those early years has persisted into the present. As Lieutenant General J. S. Aurora notes, Nehru ‘laid down some very good norms’, which ensured that ‘politics in the army has been almost absent’. ‘The army is not a political animal in any terms’, remarks Aurora, and the officers especially ‘must be the most apolitical people on earth!’

34

It is a striking fact that no army commander has ever fought an election. Aurora himself became a national hero after overseeing the liberation of Bangladesh, but neither he nor other officers have sought to convert glory won on the battlefield into political advantage. If they

have taken public office after retirement, it has been at the invitation of the government. Some, like Cariappa, have been sent as ambassadors overseas; others have served as state governors.

The army, like the civil services, is a colonial institution that has been successfully indigenized. The same might be said about the English language. In British times the intelligentsia and professional classes communicated with one another in English. So did the nationalist elite. Patel, Bose, Nehru, Gandhi and Ambedkar all spoke and wrote in their native tongue, and also in English. To reach out to regions other than one’s own, its use was indispensable. Thus a pan-Indian, anti-British consciousness was created, in good part by thinkers and activists writing in the English language.

After Independence, among the most articulate advocates for English was C. Rajagopalachari. The colonial rulers, he wrote, had ‘for certain accidental reasons, causes and purposes ... left behind [in India] a vast body of the English language’. But now it had come there was no need for it to go away. For English ‘is ours. We need not send it back to Britain along with Englishmen. He humorously added that, according to Indian tradition, it was a Hindu goddess, Saraswati, who had given birth to all the languages of the world. Thus English ‘belonged to us by origin, the originator being Saraswati, and also by acquisition’.

35

On the other hand, there were some very influential nationalists who believed that English must be thrown out of India with the British. In Nehru’s day, fitful attempts were made to replace English with Hindi as the language of inter-provincial communication. But it continued to be in use within and outside government. Visiting India in 1961 the Canadian writer George Woodcock found that, despite India’s strangeness, its ‘immense variety of custom, landscape and physical types’, this was ‘a foreign setting in which one’s language was always understood by someone nearby, and in which to speak with an English accent meant that one was seen as a kind of cousin bred out of the odd, temporary marriage of two peoples into which love and hate entered with equal intensity’.

36

After Nehru’s death the efforts to extinguish English were renewed. Despite pleas from the southern states, on 26 January 1965 Hindi became the sole official language of inter-provincial communication. As we have seen, this provoked protests so intense and furious that the order was with drawn within a fortnight. Thus English continued as the language of the central government, the superior courts and higher education.

Over the years English has confirmed, consolidated and deepened its position as the language of the pan-Indian elite. The language of the colonizers has, in independent India, become the language of power and prestige, the language of individual as well as social advancement. As the historian Sarvepalli Gopal observes, ‘that knowledge of English is the passport for employment at higher levels in all fields, is the unavoidable avenue to status and wealth and is mandatory to all those planning to migrate abroad, has meant a tremendous enthusiasm since independence to study it’. But, as Gopal also writes, English ‘may be described as the only non-regional language in India. It is a link language in a more than administrative sense, in that it counters blinkered provincialism.’

37

Those, like Nehru and Rajaji, who sought to retain English, sensed that it might help consolidate national unity and further scientific advance. That it has done, but largely unanticipated has been its role in fuelling economic growth. For behind the spectacular rise of the software industry lies the proficiency of Indian engineers in English.

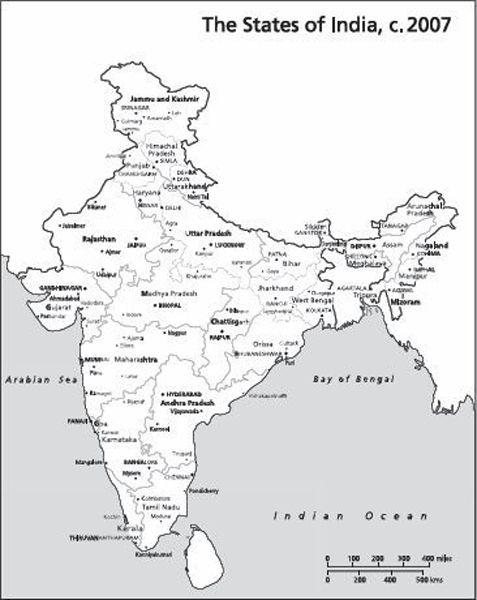

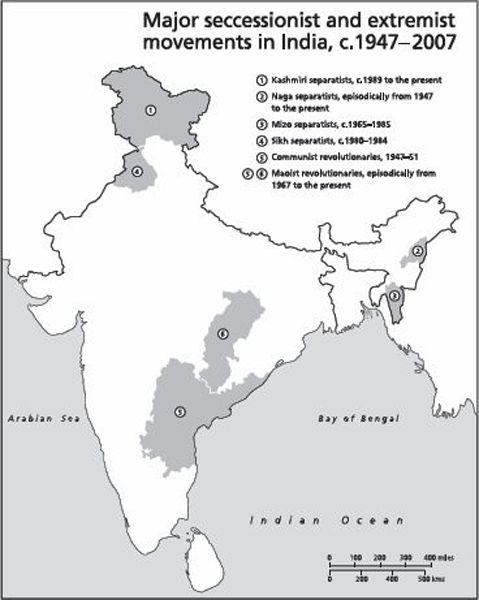

If India is roughly 50 per cent democratic, it is approximately 80 per cent united. Some parts of Kashmir and the north-east are under the control of insurgents seeking political independence. Some forested districts in central India are in the grip of Maoist revolutionaries. However, these areas, large enough in themselves, constitute considerably less than a quarter of the total land mass claimed by the Indian nation.

Over four-fifths of India, the elected government enjoys a legitimacy of power and authority. Throughout this territory the citizens of India are free to live, study, take employment and invest in businesses.

The economic integration of India is a consequence of its political integration. They act in a mutually reinforcing loop. The greater the movement of goods and capital and people across India, the greater the sense that this is, after all,

one

country. In the first decades of Independence it was the public sector that did most to further this sense of unity. In plants such as the great steel mill in Bhilai, Andhras laboured and lived alongside Punjabis and Gujaratis, fostering appreciation of other tongues, customs and cuisine, while underlining the fact that they were all part of the same nation. As the anthropologist Jonathan Parry remarks, in the Nehruvian imagination ‘Bhilai and its steel plant were

seen as bearing the torch of history, and as being as much about forging a new kind of society as about forging steel’. The attempt was not unsuccessful; among the children of the first generation of workers, themselves born and raised in Bhilai, provincial loyalties were superseded by a more inclusive patriotism, a ‘more cosmopolitan cultural style’.

38

More recently, it has been the private sector which has, if with less intent, furthered the process of national integration. Firms headquartered in Tamil Nadu set up cement plants in Haryana; doctors born and educated in Assam establish clinics in Bombay. Many of the engineers in Hyderabad’s IT industry come from Bihar. The migration is not restricted to the professional classes; there are barbers from Uttar Pradesh working in the city of Bangalore, as well as carpenters from Rajasthan. However, it must be said that the flow is not symmetrical. While the cities and towns that are ‘booming’ become ever more cosmopolitan, economically laggard states sink deeper into provincialism.

Apart from elements of politics and economics, cultural factors have also contributed to national unity. Pre-eminent here is the Hindi film. This is the great popular passion of the Indian people, watched and followed by Indians of all ages, genders, castes, classes, religions and linguistic groups.

Each formally recognized state of the Union, says the lyricist Javed Akhtar, ‘has its different culture, tradition and style. In Gujarat, you have one kind of culture, then you go to Punjab, you have another, and the same applies in Rajasthan, Bengal, Orissa or Kerala. Then Akhtar adds, ‘There is one more state in this country, and that is Hindi cinema.’

39

This is a stunning insight which asks to be developed further. As a separate state of India, Hindi cinema acts as a receptacle for all that (in a cultural sense) is most creative in the other states. Thus its actors, musicians, technicians and directors come from all parts of India. Thus also it draws ecumenically from cultural forms prevalent in different regions. For example a single song may feature both the Punjabi folk dance called the

bhangra

and its Tamil classical counterpart,

bharatan-atyam

.

Having borrowed elements from here, there and everywhere, the Hindi film then sends the synthesized product out for appreciation to the other states of the Union. The most widely revered Indians are film

stars. Yet cinema does not merely provide Indians with a common pantheon of heroes; it also gives them a common language and universe of discourse. Lines from film songs and snatches from film dialogue are ubiquitously used in conversations in schools, colleges, homes and offices – and on the street. Because it is one more state of the Union, Hindi cinema also speaks its own language – one that is understood by all the others.

The last sentence is meant literally as well as metaphorically. Hindi cinema provides a stock of social situations and moral conundrums which widely resonate with the citizenry as a whole. But, over time, it has also made the Hindi

language

more comprehensible to those who previously never spoke or understood it. When imposed by fiat by the central government, Hindi was resisted by the people of the south and the east. When conveyed seductively by the medium of cinema and television, Hindi has been accepted by them. In Bangalore and Hyderabad Hindi has become the preferred medium of communication between those who speak mutually incomprehensible tongues. Finally, one might instance the banning of Hindi films, DVDs and videos by insurgents in the north-east: this, in its own way, is a considerable tribute to the part played by the Hindi film in uniting India.

In 1888 John Strachey wrote that he could never imagine that Punjab and Madras could ever form part of a single political entity. But in 1947 they did, along with many other provinces Strachey regarded as distinct ‘nations’. While in 1947 the unity might have been mostly political, in the decades since it has been shown also to be economic, cultural and, it must be said, emotional. Perhaps many Kashmiris and Nagas yet feel alien and separate. And perhaps some revolutionaries believe that India is a land of many nationalities. But the bulk of those who are legally citizens of India are happy to be counted as such. Some four-fifths of the population, living in some four-fifths of the country, clearly feel themselves to be part of a single nation.

One might think of independent India as being Europe’s past as well as its future. It is Europe’s past, in that it has reproduced, albeit more fiercely and intensely, the conflicts of a modernizing, industrializing and urbanizing society. But it is also its future in that it anticipated, by some

fifty years, the European attempt to create a multilingual, multireligious, multiethnic, political and economic community.

Or one might compare India with the United States, a country justly celebrated as ‘the planet’s first multiethnic democracy’.

40

Born nearly two centuries later, the Republic of India is today comfortably the world’s

largest

multiethnic democracy. However, the means by which it has regulated (and moderated) relations between its constituent ethnicities have been somewhat different. For, as Samuel Huntingdon has recently argued, the American nation has been held together by a ‘credal culture’ whose ‘central elements’ have included ‘the Christian religion, Protestant values and moralism, a work ethic, the English language, British traditions of law, justice, and the limits of government power, and a legacy of European art, literature, philosophy, and music’. Indeed, ‘America was created as a Protestant society just as and for some of the reasons Pakistan and Israel were created as Muslim and Jewish societies in the twentieth century.’

The United States is, of course, a nation of immigrants. For much of the country’s history the new groups that came in merged themselves with the dominant culture. ‘Throughout American history’, writes Huntingdon, ‘people who were not white Anglo-Saxon Protestants have become Americans by adopting America’s Anglo-Protestant culture and political values’. Of late, however, newer groups of immigrants have tended to maintain their distinct identities. The largest of these are the Hispanics, who live in enclaves where they cook their own food, listen to their own kind of music, follow their own faith and – most importantly – speak their own language. Huntingdon worries that if these communities are not quickly brought in to line, they will ‘transform America as a whole into a bilingual, bicultural society .