Infamy (51 page)

Authors: Richard Reeves

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century, #State & Local, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY)

Military Intelligence Service recruit Kenny Yasui served in Burma and had swam alone to an island and persuaded the Japanese garrison there to surrender.

In Europe, German and Italian soldiers surrendered in large numbers before the ferocious fighting of Japanese American units. A German officer captured by a Japanese American shouted, “You’re not an American. You’re supposed to be on our side.”

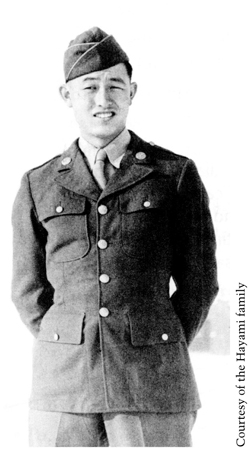

Stanley Hayami kept a diary of life at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, agonizing over his high school grades and ambitions before joining the army as soon as he graduated.

Sergeant Ben Kuroki flew fifty-eight missions in Europe and the Pacific and toured America as a war hero. One of his stops was at Heart Mountain, where he thrilled young people, but he never heard the threats from some of the pro-Japan groups.

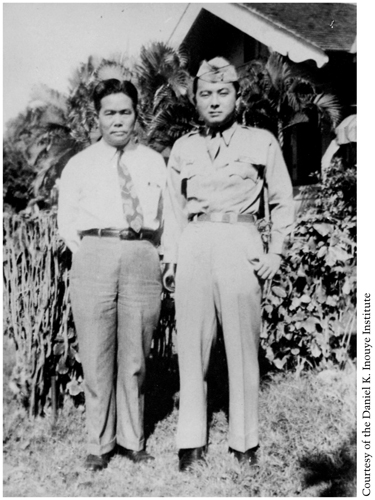

Lieutenant Daniel Inouye, a winner of the Medal of Honor as a platoon leader in Italy, returned home to Hawaii with a metal hook, replacing the arm he lost in combat. Standing here with his father, he later became a long-serving United States senator.

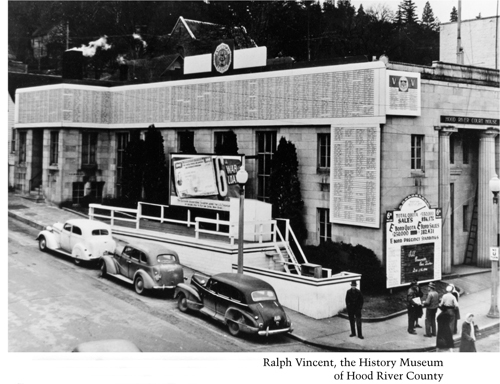

Members of the American Legion Post in Hood River, Oregon, became a national symbol of prejudice when they painted over the names of Japanese Americans serving in Europe on the “Wall of Honor” at the local courthouse.

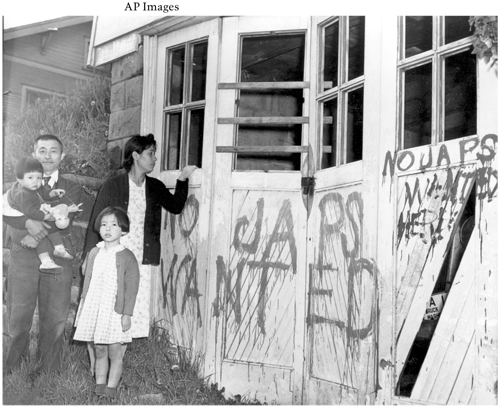

As the American Japanese returned to their homes after the war, a few found that their neighbors had helped preserve their businesses and farms. Far more were still treated as enemies.

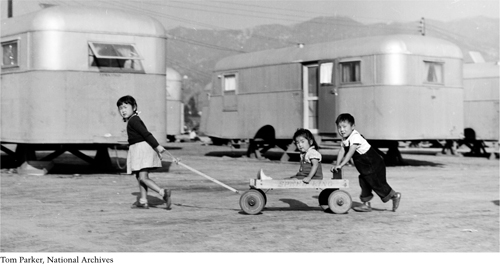

Many of the evacuees, having lost everything, became residents of shoddy towns, trailer parks, and abandoned army barracks.

General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell presented a Distinguished Service Cross to Mary Masuda in honor of her brother, who was killed while serving in Italy. Upon hearing about her family’s difficult return home, Stilwell said he would be glad to form a “pick-axe” brigade to protect them.

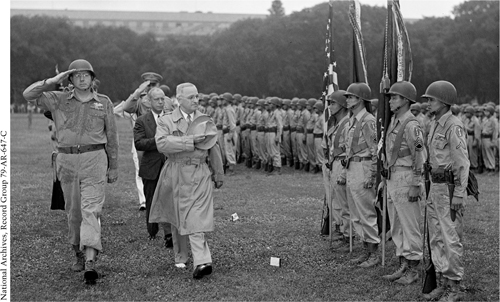

President Harry S. Truman saluted the all–Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most honored combat unit per capita in American military history. Truman shook the hand of Private Wilson Makabe (left), who lost a leg in combat. He addressed the veterans: “You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice and you have won.”

I had wanted to write this book for a long time for the simplest of reasons: to answer the question, “How could this have happened here?” I had wandered the bare ruins of several of the “Relocation Centers” of World War II, hoping I might hear the voices of the Americans there. I couldn’t, of course; there was only the howling wind. The winds became words late in the 1960s and 1970s when young Japanese Americans, inspired in part by the black civil rights movement and anti–Vietnam War protest, urged their families to tell their stories. They created Japanese American foundations and museums; writers and researchers collected and saved those words in thousands of interviews and oral histories describing a dark stain on American history. I am in debt to thousands of Americans who became historical archaeologists to dig up a story sure to be lost in the tales of World War II and the American ascendance in the second half of the twentieth century. So I am grateful to the witnesses and scholars of this extraordinary time in American history. I am especially grateful to two of my guides through this world: Lane Ryo Hirabayashi of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Robert Asahina, who pointed me in directions I never would have found on my own.

I am also in debt to two extraordinary young women: my assistant Sue Gifford and Emi Ikkanda, my editor, under John Sterling at Henry Holt and Company. Emi and I may not have always agreed on how to analyze this American history, but this would be less of a book without her passions and insights. Michael Shashoua helped with research in New Mexico. There are a million moving parts in this story and no one could take it on without the smarts of many other people. It was an adventure and I am grateful to so many people from the National Park Service and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles who took this journey with me. They are a national treasure.

On a more personal basis, I am deeply grateful to hundreds friends and members of my family in Los Angeles, New York, Sag Harbor, and Paris. I worked on this book during the most difficult events of my life and could not have seen it through without their love and help. I am leaving out many more names than I am including here, but I must mention my children, Jeffrey, Fiona, and Cynthia Reeves, and Conor O’Neill, Colin O’Neill and his wife Deneen, and Mary Ann and Jack Garvey, Ann Beirne, Mary and Roger Mulvihill, my agent, Amanda Urban, not only for her usual professional excellence but for many other things, and her husband, Ken Auletta, Nancy Candage, Dr. Janet Pregler, Marcia and Paul Herman, Millie Harmon Meyers, Alice Mayhew, Leslie Stahl and Aaron Latham, Kay Eldredge and Jim Salter, Myrna and Paul Davis, Amanda Kyser and Robert Sam Anson, Gail Sheehy and Clay Felker, Bina and Walter Bernard, Ellen Chesler and Matt Mallow, Jean Vallely Graham, Meredith and Tom Brokaw, President Barack Obama, Cynthia and Steven Brill, Liv Ullman, Susan Alberti, Fran and Roger Diamond, Susan and Alan Friedman, Heidi Shulman and Mickey Kantor, Nancy and Len Jacoby, Roger Gould, Ken Turan and Patty Williams, Ron Rogers and Lisa Specht, Alice and David Clement, Diane Wayne and Ira Reiner, Aileen Adams and Geoff Cowan, Susan and Donald Rice, Nancy and Miles Rubin, Linda Douglass and John Phillips, my colleagues at the Annenberg School of the University of Southern California, most of all Mary Murphy, Nancy and Richard Asthalter, Berna and Lee Huebner, Connie and Dominique Borde, Elizabeth Johnston, Pat Thompson and Jim Bitterman, Pat and Walter Wells, Judith Symonds, Sarah Stackpole and Ward Just, Ina and Robert Caro, Sarah and Mitch Rosenthal, Marlise and Alan Riding, Lynne and Russell Kelley, Pat Hynes, Ralph Schlosstein and Jane Hartley, Deb and Kevin McEneaney, Susan Lacy and Halstead Welles, Kathleen Brown and Van Gordon Sauter, Anne Graves, and, above all, Patricia Rivera.