Influence: Science and Practice (31 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

One especially revealing question gives us a clue: “If the community had remained in San Francisco, would Reverend Jones’ suicide command have been obeyed?” A highly speculative question to be sure, but the expert most familiar with the People’s Temple had no doubt about the answer. Dr. Louis Jolyon West, then chairman of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA and director of its neuropsychiatric unit, was an authority on cults who had observed the People’s Temple for eight years prior to the Jonestown deaths. When interviewed in the immediate aftermath, he made what strikes me as an inordinately instructive statement: “This wouldn’t have happened in California. But they lived in total alienation from the rest of the world in a jungle situation in a hostile country.”

Although lost in the welter of commentary following the tragedy, West’s observation, together with what we know about the principle of social proof, seems to me quite important to a satisfactory understanding of the compliant suicides. To my mind, the single act in the history of the People’s Temple that most contributed to the members’ mindless compliance that day occurred a year earlier with the relocation of the Temple to a jungled country of unfamiliar customs and people. If we are to believe the stories of Jim Jones’ malevolent genius, he realized fully the massive psychological impact such a move would have on his followers. All at once, they found themselves in a place they knew nothing about. South America, and the rain forests of Guyana, especially, were unlike anything they had experienced in San Francisco. The environment—both physical and social—into which they were dropped must have seemed dreadfully uncertain.

Ah, uncertainty—the right-hand man of the principle of social proof. We have already seen that when people are uncertain, they look to the actions of others to guide their own actions. In the alien, Guyanese environment, then, Temple members were very ready to follow the lead of others. As we have also seen, it is others of a special kind whose behavior will be most unquestioningly followed: similar others. Therein lies the awful beauty of Reverend Jones’ relocation strategy. In a country like Guyana, there were no similar others for a Jonestown resident but the people of Jonestown itself.

Bodies lay in orderly rows at Jonestown, displaying the most spectacular act of compliance of our time.

What was right for a member of the community was determined to a disproportionate degree by what other community members—influenced heavily by Jones—did and believed. When viewed in this light, the terrible orderliness, the lack of panic, the sense of calm with which these people moved to the vat of poison and to their deaths seems more comprehensible. They hadn’t been hypnotized by Jones; they had been convinced—partly by him but, more important, by the principle of social proof—that suicide was the correct conduct. The uncertainty they surely felt upon first hearing the death command must have caused them to look around them for a definition of the appropriate response.

It is worth particular note that they found two impressive pieces of social evidence, each pointing in the same direction. The first was the initial set of their compatriots, who quickly and willingly took the poison drafts. There will always be a few such fanatically obedient individuals in any strong leader-dominated group. Whether, in this instance, they had been specially instructed beforehand to serve as examples or whether they were just naturally the most compliant with Jones’ wishes is difficult to know. No matter; the psychological effect of the actions of those individuals must have been potent. If the suicides of similar others in news stories can influence total strangers to kill themselves, imagine how enormously more compelling such an act would be when performed without hesitation by one’s neighbors in a place like Jonestown. The second source of social evidence came from the reactions of the crowd itself. Given the conditions, I suspect that what occurred was a large-scale instance of the pluralistic ignorance phenomenon. Each Jonestowner looked to the actions of surrounding individuals to assess the situation and—finding calmness because everyone else, too, was surreptitiously assessing rather than reacting—“learned” that patient turntaking was the correct behavior. Such misinterpreted, but nonetheless convincing, social evidence would be expected to result precisely in the ghastly composure of the assemblage that waited in the tropics of Guyana for businesslike death.

From my own perspective, most attempts to analyze the Jonestown incident have focused too much on the personal qualities of Jim Jones. Although he was without question a man of rare dynamism, the power he wielded strikes me as coming less from his remarkable personal style than from his understanding of fundamental psychological principles. His real genius as a leader was his realization of the limitations of individual leadership. No leader can hope to persuade, regularly and single-handedly, all the members of the group. A forceful leader can reasonably expect, however, to persuade some sizable proportion of group members. Then the raw information that a substantial number of group members has been convinced can, by itself, convince the rest (Watts & Dodd, 2007). Thus, the most influential leaders are those who know how to arrange group conditions to allow the principle of social proof to work in their favor.

It is in this that Jones appears to have been inspired. His masterstroke was the decision to move the People’s Temple community from urban San Francisco to the remoteness of equatorial South America, where the conditions of uncertainty and exclusive similarity would make the principle of social proof operate for him as perhaps nowhere else. There a settlement of a thousand people, much too large to be held in persistent sway by the force of one man’s personality, could be changed from a following into a

herd

. As slaughterhouse operators have long known, the mentality of a herd makes it easy to manage. Simply get some members moving in the desired direction and the others—responding not so much to the lead animal as to those immediately surrounding them—will peacefully and mechanically go along. The powers of the amazing Reverend Jones, then, are probably best understood not in terms of his dramatic personal style but in his profound knowledge of the art of social jujitsu.

Defense

I began this chapter with an account of the relatively harmless practice of laugh tracking and moved on to stories of murder and suicide—all explained by the principle of social proof. How can we expect to defend ourselves against a weapon of influence that pervades such a vast range of behavior? The difficulty is compounded by the realization that, most of the time, we don’t want to guard against the information that social proof provides. The evidence it offers about the way we should act is usually valid and valuable (Surowiecki, 2004). With it we can cruise confidently through countless decisions without having to investigate the detailed pros and cons of each. In this sense, the principle of social proof equips us with a wonderful kind of automatic pilot device not unlike that aboard most aircraft.

Yet there are occasional, but real, problems with automatic pilots. Those problems appear whenever the flight information locked into the control mechanism is wrong. In these instances, we will be taken off course. Depending on the size of the error, the consequences can be severe; but, because the automatic pilot afforded by the principle of social proof is more often an ally than an enemy, we can’t be expected to want simply to disconnect it. Thus, we are faced with a classic problem: how to make use of a piece of equipment that simultaneously benefits and imperils our welfare.

Fortunately, there is a way out of the dilemma. Because the disadvantages of automatic pilots arise principally when incorrect data have been put into the control system, our best defense against these disadvantages is to recognize when the data are in error. If we can become sensitive to situations in which the social proof automatic pilot is working with inaccurate information, we can disengage the mechanism and grasp the controls when we need to.

Sabotage

There are two types of situations in which incorrect data cause the principle of social proof to give us poor counsel. The first occurs when the social evidence has been purposely falsified. Invariably these situations are manufactured by exploiters intent on creating the

impression

—reality be damned—that a multitude is performing the way the exploiters want us to perform. The canned laughter of TV comedy shows is one variety of faked data of this sort, but there is a great deal more, and much of the fakery is strikingly obvious.

For instance, canned responses are not unique to the electronic media or even to the electronic age. In fact, the heavy-handed exploitation of the principle of social proof can be traced through the history of grand opera, one of our most venerable art forms. This is the phenomenon called claquing, said to have begun in 1820 by a pair of Paris opera-house habitués named Sauton and Porcher. The men were more than opera-goers, though. They were businessmen whose product was applause.

Organizing under the title L’Assurance des Succès Dramatiques, they leased themselves and their employees to singers and opera managers who wished to be assured of an appreciative audience response. So effective were Sauton and Porcher in stimulating genuine audience reaction with their rigged reactions that, before long, claques (usually consisting of a leader—

chef de claque

—and several individual

claqueurs

) had become an established and persistent tradition throughout the world of opera. As music historian Robert Sabin (1964) notes, “By 1830 the claque was a full-bloom institution, collecting by day, applauding by night, all in the honest open. . . . But it is altogether probable that neither Sauton, nor his ally Porcher, had a notion of the extent to which their scheme of paid applause would be adopted and applied wherever opera is sung.”

As claquing grew and developed, its practitioners offered an array of styles and strengths. In the same way that laugh-track producers hire individuals who excel in titters, chuckles, or belly laughs, the claques spawned their own specialists—the

pleureuse

, chosen for her ability to weep on cue; the

bisseur

, who called “

bis

” (repeat) and “encore” in ecstatic tones; and, in direct kinship with today’s laugh-track performer, the

rieur

, selected for the infectious quality of his laugh.

For our purposes, though, the most instructive parallel to modern forms of canned response is the conspicuous character of the fakery. No special need was seen to disguise or vary the claque, who often sat in the same seats, performance after performance, year after year, led by a

chef de claque

two decades into his position. Even the monetary transactions were not hidden from the public. Indeed, one hundred years after the birth of claquing, a reader of the London

Musical Times

could scan the advertised rates of the Italian

claqueurs

(see

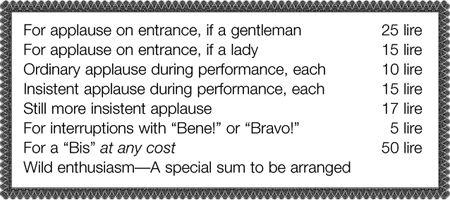

Figure 4.3

). Whether in the world of

Rigoletto

or TV sit-coms, then, audiences have been successfully manipulated by those who use social evidence, even when that evidence has been openly falsified.

Figure 4.3

Advertised Rates of the Italian Claque

From “ordinary applause” to “wild enthusiasm,”

claqueurs

offered their services in an audaciously public fashion—in this case, in a newspaper read by many of the audience members they fully expected to influence.

Claque

,

whirr

.

What Sauton and Porcher realized about the mechanical way that we abide by the principle of social proof is understood as well by a variety of today’s profiteers. They see no need to hide the manufactured nature of the social evidence they provide—witness the amateurish quality of the average TV laugh track. They seem almost smug in the recognition of our predicament: Either we must allow them to fool us or we must abandon the precious automatic pilots that make us so vulnerable to their tricks. In their certainty that they have us trapped, however, such exploiters have made a crucial mistake. The laxity with which they construct phony social evidence gives us a way to fight back.