Influence: Science and Practice (5 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

And even when it is not initially successful, she can then mark the article “Reduced” and sell it to bargain-hunters at its original price while still taking advantage of their expensive = good reaction to the inflated figure.

By no means is my friend original in this last use of the expensive = good rule to snare those seeking a bargain. Culturist and author Leo Rosten gives the example of the Drubeck brothers, Sid and Harry, who owned a men’s tailor shop in Rosten’s neighborhood in the 1930s. Whenever Sid had a new customer trying on suits in front of the shop’s three-sided mirror, he would admit to a hearing problem and repeatedly request that the man speak more loudly to him. Once the customer had

found a suit he liked and asked for the price, Sid would call to his brother, the head tailor, at the back of the room, “Harry, how much for this suit?” Looking up from his work—and greatly exaggerating the suit’s true price—Harry would call back, “For that beautiful, all wool suit, forty-two dollars.” Pretending not to have heard and cupping his hand to his ear, Sid would ask again. Once more Harry would reply, “Forty-two dollars.” At this point, Sid would turn to the customer and report, “He says twenty-two dollars.” Many a man would hurry to buy the suit and scramble out of the shop with his expensive = good bargain before poor Sid discovered the “mistake.”

Jujitsu

A woman employing the Japanese martial art form called jujitsu would use her own strength only minimally against an opponent. Instead, she would exploit the power inherent in such naturally present principles as gravity, leverage, momentum, and inertia. If she knows how and where to engage the action of these principles she can easily defeat a physically stronger rival. And so it is for the exploiters of the weapons of automatic influence that exist naturally around us. The profiteers can commission the power of these weapons for use against their targets while exerting little personal force. This last feature of the process gives the profiteers an enormous additional benefit—the ability to manipulate without the appearance of manipulation. Even the victims themselves tend to see their compliance as a result of the action of natural forces rather than the designs of the person who profits from that compliance.

An example is in order. There is a principle in human perception, the contrast principle, that affects the way we see the difference between two things that are presented one after another. Simply put, if the second item is fairly different from the first, we will tend to see it as

more

different than it actually is. So if we lift a light object first and then lift a heavy object, we will estimate the second object to be heavier than if we had lifted it without first lifting the light one. The contrast principle is well established in the field of psychophysics and applies to all sorts of perceptions besides weight. If we are talking to a very attractive individual at a party and are then joined by an unattractive individual, the second will strike us as less attractive than he or she actually is.

8

8

Some researchers warn that the unrealistically attractive people portrayed in the popular media (actors, actresses, models) may cause us to be less satisfied with the looks of the genuinely available romantic possibilities around us. For instance, one study demonstrated that exposure to the exaggerated sexual attractiveness of nude pinup bodies (in such magazines as

Playboy

and

Playgirl

) causes people to become less pleased with the sexual desirability of their current spouse or live-in mate (Kenrick, Gutierres, & Goldberg, 1989).

Another demonstration of perceptual contrast is sometimes employed in psychophysics laboratories to introduce students to the principle. Each student takes a turn sitting in front of three pails of water—one cold, one at room temperature, and one hot. After placing one hand in the cold water and one in the hot water, the student is told to place both hands in the room-temperature water simultaneously. The look of amused bewilderment that immediately registers tells the story: Even though both hands are in the same bucket, the hand that has been in the cold water feels as if it is now in hot water, while the one that was in the hot water feels as if it is now in cold water. The point is that the same thing—in this instance, room-temperature water—can be made to seem very different depending on the nature of the event that precedes it.

Be assured that the nice little weapon of influence provided by the contrast principle does not go unexploited. The great advantage of this principle is not only that it works but also that it is virtually undetectable (Tormala & Petty, 2007). Those who employ it can cash in on its influence without any appearance of having structured the situation in their favor. Retail clothiers are a good example. Suppose a man enters a fashionable men’s store and says that he wants to buy a three-piece suit and a sweater. If you were the salesperson, which would you show him first to make him likely to spend the most money? Clothing stores instruct their sales personnel to sell the costly item first. Common sense might suggest the reverse: If a man has just spent a lot of money to purchase a suit, he may be reluctant to spend much more on the purchase of a sweater; but the clothiers know better. They behave in accordance with what the contrast principle would suggest: Sell the suit first, because when it comes time to look at sweaters, even expensive ones, their prices will not

seem

as high in comparison. The same principle applies to a man who wishes to buy the accessories (shirt, shoes, belt) to go along with his new suit. Contrary to the commonsense view, the evidence supports the contrast principle prediction.

It is much more profitable for salespeople to present the expensive item first; to fail to do so will lose the influence of the contrast principle and will also cause the principle to work actively against them. Presenting an inexpensive product first and following it with an expensive one will make the expensive item seem even more costly as a result—hardly a desirable consequence for most sales organizations. So, just as it is possible to make the same bucket of water appear to be hotter or colder depending on the temperature of previously presented water, it is possible to make the price of the same item seem higher or lower depending on the price of a previously presented item.

Perceptual Contrast

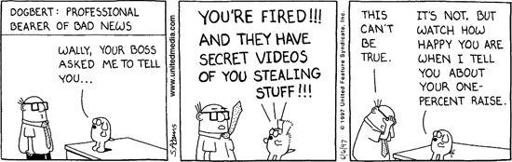

A one-percent solution.

DILBERT:

© Scott Adams. Distributed by United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

Clever use of perceptual contrast is by no means confined to clothiers. (See

Figure 1.1

.) I came across a technique that engaged the contrast principle while I was investigating, undercover, the compliance tactics of real estate companies. To “learn the ropes,” I accompanied a salesman on a weekend of showing houses to prospective home buyers. The salesman—we can call him Phil—was to give me tips to help me through my break-in period. One thing I quickly noticed was that whenever Phil began showing a new set of customers potential buys, he would start with a couple of undesirable houses. I asked him about it, and he laughed. They were what he called “setup” properties. The company maintained a run-down house or two on its lists at inflated prices. These houses were not intended to be sold to customers but only to be shown to them, so that the genuine properties in the company’s inventory would benefit from the comparison. Not all the sales staff made use of the setup houses, but Phil did. He said he liked to watch his prospects’ “eyes light up” when he showed the places he really wanted to sell them after they had seen the rundown houses. “The house I got them spotted for looks really great after they’ve first looked at a couple of dumps.”

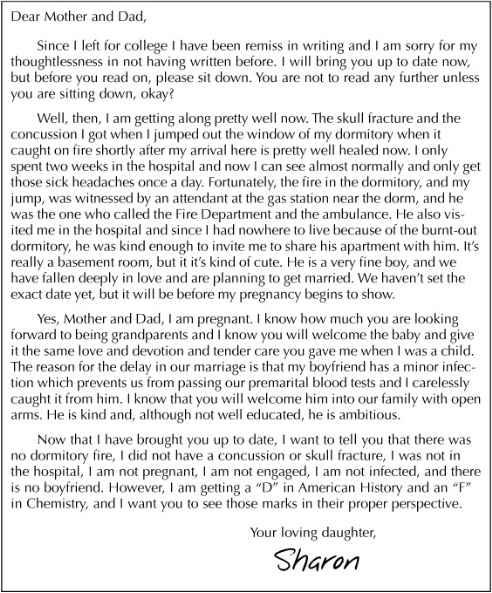

Figure 1.1

Perceptual Contrast and the College Coed

Sharon may be failing chemistry, but she’d get an “A” in psychology.

Automobile dealers use the contrast principle by waiting until the price of a car has been negotiated before suggesting one option after another. In the wake of a many-thousand-dollar deal, the hundred or so dollars extra for a nicety like an upgraded CD player seems almost trivial in comparison. The same will be true of the added expense of accessories like tinted windows, better tires, or special trim that the dealer might suggest in sequence. The trick is to bring up the options independently of one another so that each small price will seem petty when compared to the already determined much larger price. As veteran car buyers can attest, many a budget-sized final price figure has ballooned out of proportion from the addition of all those seemingly little options. While the customers stand, signed contract in hand, wondering what happened and finding no one to blame but themselves, the car dealer stands smiling the knowing smile of the jujitsu master.

READER’S REPORT 1.2

From a University of Chicago Business School Student

While waiting to board a flight at O’Hare, I heard a desk agent announce that the flight was overbooked and that, if passengers were willing to take a later plane, they would be compensated with a voucher worth $10,000! Of course, this exaggerated amount was a joke. It was supposed to make people laugh. It did. But I noticed that when he then revealed the

actual

offer (a $200 voucher), there were no takers. In fact, he had to raise the offer twice, to $300 and then $500, before he got any volunteers.

I was reading your book at the time, and I realized that, although he got his laugh, according to the contrast principle, he screwed up. He’d arranged things so that compared to $10,000, a couple hundred bucks seemed like a pittance. That was an expensive laugh. It cost his airline an extra $300 per volunteer.

Author’s note:

Any ideas on how the desk agent could have used the contrast principle to his advantage rather than his detriment? Perhaps he could have started with a $5 joke offer and then revealed the true (and now much more attractive-sounding) $200 amount. Under those circumstances, I’m pretty sure he would have secured his laugh and his volunteers.

Summary

Ethologists, researchers who study animal behavior in the natural environment, have noticed that among many animal species behavior often occurs in rigid and mechanical patterns. Called fixed-action patterns, these mechanical behavior sequences are noteworthy in their similarity to certain automatic (

click

,

whirr

) responding by humans. For both humans and subhumans, the automatic behavior patterns tend to be triggered by a single feature of the relevant information in the situation. This single feature, or trigger feature, can often prove very valuable by allowing an individual to decide on a correct course of action without having to analyze carefully and completely each of the other pieces of information in the situation.

The advantage of such shortcut responding lies in its efficiency and economy; by reacting automatically to a usually informative trigger feature, an individual preserves crucial time, energy, and mental capacity. The disadvantage of such responding lies in its vulnerability to silly and costly mistakes; by reacting to only a piece of the available information (even a normally predictive piece), an individual increases the chances of error, especially when responding in an automatic, mindless fashion. The chances of error increase even further when other individuals seek to profit by arranging (through manipulation of trigger features) to stimulate a desired behavior at inappropriate times.