Influence: Science and Practice (6 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Much of the compliance process (wherein one person is spurred to comply with another person’s request) can be understood in terms of a human tendency for automatic, shortcut responding. Most individuals in our culture have developed a set of trigger features for compliance, that is, a set of specific pieces of information that normally tell us when compliance with a request is likely to be correct and beneficial. Each of these trigger features for compliance can be used like a weapon (of influence) to stimulate people to agree to requests.

Study Questions

Content Mastery

- What are fixed-action patterns among animals? How are they similar to some types of human functioning? How are they different?

- What makes automatic responding in humans so attractive? So dangerous?

Critical Thinking

- Suppose you were an attorney representing a woman who broke her leg in a department store and was suing the store for $100,000 in damages. Knowing only what you do about perceptual contrast, what could you do during the trial to make the jury see $100,000 as a reasonable, even small, award?

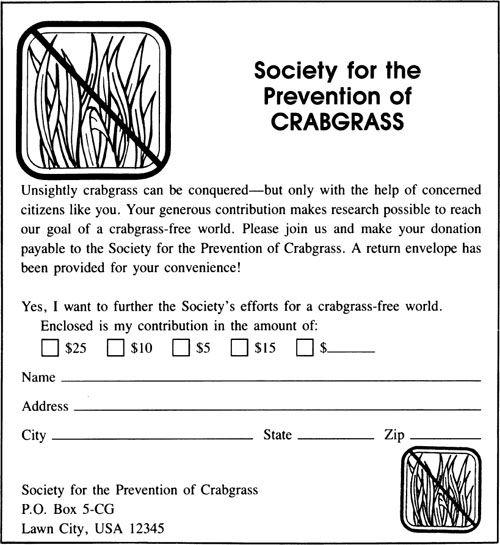

- The charity request card in

Figure 1.2

seems rather ordinary except for the odd sequencing of the donation request amounts. Explain why, according to the contrast principle, placing the smallest donation figure between two larger figures is an effective tactic to prompt more and larger donations. - What points do the following quotes make about the dangers of

click-whirr

responding?

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Albert Einstein “The greatest lesson in life is to know that even fools are sometimes right.” Winston Churchill - How does the photograph that opens this chapter reflect the topic of the chapter?

Figure 1.2

Charity Request Appeal

Chapter 2

Reciprocation

The Old Give and Take . . .and Take

Pay every debt, as if God wrote the bill.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

S

EVERAL YEARS AGO, A UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR TRIED A LITTLE

experiment. He sent Christmas cards to a sample of perfect strangers. Although he expected some reaction, the response he received was amazing—holiday cards addressed to him came pouring back from people who had never met nor heard of him. The great majority of those who returned cards never inquired into the identity of the unknown professor. They received his holiday greeting card,

click

, and

whirr

, they automatically sent cards in return (Kunz & Woolcott, 1976).

While small in scope, this study shows the action of one of the most potent of the weapons of influence around us—the rule of reciprocation. The rule says that we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us. If a woman does us a favor, we should do her one in return; if a man sends us a birthday present, we should remember his birthday with a gift of our own; if a couple invites us to a party, we should be sure to invite them to one of ours. By virtue of the reciprocity rule, then, we are

obligated

to the future repayment of favors, gifts, invitations, and the like. So typical is it for indebtedness to accompany the receipt of such things that a phrase like “much obliged” has become a synonym for “thank you,” not only in the English language but in others as well (such as with the Portuguese term “obrigado”). The future reach of the obligation is nicely connoted in a Japanese word for thank you, “sumimasen,” which means “this will not end” in its literal form.

The impressive aspect of reciprocation with its accompanying sense of obligation is its pervasiveness in human culture. It is so widespread that, after intensive study, Alvin Gouldner (1960), along with other sociologists, report that all human societies subscribe to the rule.

1

Within each society it seems pervasive also; it permeates exchanges of every kind. Indeed, it may well be that a developed system of indebtedness flowing from the rule of reciprocation is a unique property of human culture. The noted archaeologist Richard Leakey ascribes the essence of what makes us human to the reciprocity system. He claims that we are human because our ancestors learned to share food and skills “in an honored network of obligation” (Leakey & Lewin, 1978). Cultural anthropologists view this “web of indebtedness” as a unique adaptive mechanism of human beings, allowing for the division of labor, the exchange of diverse forms of goods and different services, and the creation of interdependencies that bind individuals together into highly efficient units (Ridley, 1997; Tiger & Fox, 1989).

1

Certain societies have formalized the rule into ritual. Consider for example the Vartan Bhanji, an institutionalized custom of gift exchange common to parts of Pakistan and India. In commenting upon the Vartan Bhanji, Gouldner (1960) remarks:

It is . . . notable that the system painstakingly prevents the total elimination of outstanding obligations. Thus, on the occasion of a marriage, departing guests are given gifts of sweets. In weighing them out, the hostess may say, “These five are yours,” meaning “These are a repayment for what you formerly gave me,” and then she adds an extra measure, saying, “These are mine.” On the next occasion, she will receive these back along with an additional measure which she later returns, and so on. (p. 175)

It is a sense of future obligation that is critical to produce social advances of the sort described by Tiger and Fox. A widely shared and strongly held feeling of future obligation made an enormous difference in human social evolution because it meant that one person could give something (for example, food, energy, care) to another with confidence that the gift was not being lost. For the first time in evolutionary history, one individual could give away any of a variety of resources without actually giving them away. The result was the lowering of the natural inhibitions against transactions that must be

begun

by one person’s providing personal resources to another. Sophisticated and coordinated systems of aid, gift giving, defense, and trade became possible, bringing immense benefits to the societies that possessed them. With such clearly adaptive consequences for the culture, it is not surprising that the rule for reciprocation is so deeply implanted in us by the process of socialization we all undergo.

Although obligations extend into the future, their span is not unlimited. Especially for relatively small favors, the desire to repay seems to fade with time (Burger et al., 1997; Flynn, 2002). But, when gifts are of the truly notable and memorable sort, they can be remarkably long-lived. I know of no better illustration of the way reciprocal obligations can reach long and powerfully into the future than the perplexing story of $5,000 of relief aid that was exchanged between Mexico and Ethiopia. In 1985, Ethiopia could justly lay claim to the greatest suffering and privation in the world. Its economy was in ruin. Its food supply had been ravaged by years of drought and internal war. Its inhabitants were dying by the thousands from disease and starvation. Under these circumstances, I would not have been surprised to learn of a $5,000 relief donation from Mexico to that wrenchingly needy country. I remember my feeling of amazement, though, when a brief newspaper item I was reading insisted that the aid had gone in the opposite direction. Native officials of the Ethiopian Red Cross had decided to send the money to help the victims of that year’s earthquakes in Mexico City.

It is both a personal bane and a professional blessing that whenever I am confused by some aspect of human behavior, I feel driven to investigate further. In this instance, I was able to track down a fuller account of the story. Fortunately, a journalist who had been as bewildered as I by the Ethiopians’ actions had asked for an explanation. The answer he received offered eloquent validation of the reciprocity rule: Despite the enormous needs prevailing in Ethiopia, the money was being sent to Mexico because, in 1935, Mexico had sent aid to Ethiopia when it was invaded by Italy (“Ethiopian Red Cross,” 1985). So informed, I remained awed, but I was no longer puzzled. The need to reciprocate had transcended great cultural differences, long distances, acute famine, many years, and immediate self-interest. Quite simply, a half-century later, against all counter-vailing forces, obligation triumphed.

If a half-century-long obligation appears to be a one of a kind sort of thing, explained by some unique feature of Ethiopian culture, consider the solution to

another initially baffling case. On May 27, 2007, a Washington, DC-based government official named Christiaan Kroner spoke to a news reporter with unconcealed pride in the governmental action that had followed the Hurricane Katrina disaster, detailing how “pumps, ships, helicopters, engineers, and humanitarian relief” had been sent both rapidly and adeptly to the flooded city of New Orleans and to many other sites of the calamity (Hunter, 2007). Say what? In the face of widespread recognition of the Federal government’s scandalously delayed and monstrously inept reaction to the tragedy, how could he possibly make such a statement? For example, at the time of his claim, the government’s vaunted Road Home program designed to aid Louisiana homeowners still hadn’t delivered funds to 80 percent of those requesting assistance, even though nearly eighteen months had past. Could it be that Mr. Kroner is even more shameless than most politicians are reputed to be? It turns out not. In fact, he was wholly justified in feeling gratified by his government’s efforts because he was not an official of the United States; instead, he was the Dutch ambassador to the United States, and he was speaking of the remarkable assistance rendered to the Katrina-racked American Gulf Coast by the Netherlands.

But, with that matter resolved, an equally puzzling question arises: Why the Netherlands? Other countries had offered aid in the aftermath of the storm. But none had come close to matching the immediate and ongoing commitment of the Dutch to the region. Indeed, Mr. Kroner went on to assure the flood victims that his government would be with them for the long term, stating that “everything we can do and everything Louisiana wants us to do, we are ready to do.” Mr. Kroner also suggested one telling reason for this extraordinary willingness to help: The Netherlands owed it to New Orleans—for more than half a century. On January 31, 1953 an unrelenting gale pushed fierce North Sea waters across a quarter-million acres of his country, leveling dikes, levees, and thousands of homes while killing 2,000 residents. Soon thereafter, Dutch officials requested and received aid and technical assistance from their counterparts in New Orleans, which resulted in the construction of a new system of water pumps that have since protected the country from similarly destructive floods. One wonders why it seems that the same levels of support for New Orleans provided by officials of a foreign government never came from the city’s own national government. Perhaps the officials of that government didn’t think they owed New Orleans enough.