Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) (3 page)

Read Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) Online

Authors: Jack D. Edinger Colleen E. Carney

have to give a speech upon waking significantly increases the time it takes to fall

asleep (sleep onset latency) (Gross & Borkovec, 1982). Stress-induced worry also

decreases slow (delta) wave intensity in the first sleep cycle of normal subjects (Hall,

Buysse, Reynolds, Kupfer, & Baum, 1996), and this physiological change tends to

make sleep subjectively “lighter” and more objectively disrupted. Similarly, induc-

ing poor sleep artificially with the administration of a stimulant increases next-day

anxiety (Bonnet & Arand, 1992). It is fairly common for those with clinical levels

of anxiety to report insomnia, and the rate of comorbid anxiety disorders in those

with insomnia is approximately 24% (Ford & Kamerow, 1989).

Whereas previous psychiatric conceptualizations viewed insomnia as a mere

symptom of psychiatric disorders, contemporary viewpoints recognize the ample

The Case of Comorbid Insomnia: More Nosological Issues

5

evidence for insomnia as an often comorbid, treatment-worthy condition. Anxiety

disorders often precede the onset of insomnia (Johnson, Roth, & Breslau, 2006;

Ohayon & Roth, 2003), but insomnia also can occur prior to the onset of anxiety

disorders suggesting a possible etiological role of sleep disturbance for some with

such conditions. For example, the presence of insomnia is predictive of future anxi-

ety disorders ascertained one to 45 years after the baseline interview even after

other significant predictors were statistically controlled (Ford & Kamerow, 1989;

Livingston, Blizard, & Mann, 1993).

Traditionally, PI and Insomnia Related to a Mental Disorder (IMD) or so-called

secondary insomnia have been considered separate disorders. However, recently the

need for this diagnostic distinction has been debated. Distinguishing between pri-

mary and secondary insomnias may have led to a traditional clinical misconception

that the insomnia of those with comorbid conditions is merely a product of the

larger comorbid disease process (e.g., a secondary condition) that fails to merit

separate diagnostic or treatment attention. Arguably, such a conceptualization has

also led to a lack of proper treatment attention and possible diagnostic problems.

Clinical practice studies reveal a lack of attention for sleep complaints, and a mis-

understanding of the predominant features of various insomnia diagnoses (Haponik,

Frye, Richards, Wymer, & Hinds, 1996). For example, in a survey of over 3,000

general practitioners, the most common symptom used to identify depression was

the presence of a sleep complaint or insomnia (Krupinski & Tiller, 2001). In the

same study, only 28% of those diagnosed with MDD actually met DSM-IV criteria

for this condition; the remaining patients were incorrectly diagnosed with MDD

when they actually had untreated insomnia. It is unclear as to how often this occurs

in anxiety disordered clients. We examined this question more broadly by examin-

ing those with insomnia with an Axis I Mental Disorder (IMD) and those with

insomnia only (PI) (Carney, Edinger, Krystal, Stepanski, & Kirby, 2005). One third

of these insomnia patients were diagnosed by sleep specialists via clinical interview

with Insomnia Related to a Mental Disorder. These sleep experts did not have

access to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) information –

instead they had access to a range of sleep related information such as sleep logs,

polysomnography, and a sleep history questionnaire. Of those diagnosed with IMD,

almost one third did

not

have a SCID-verified disorder on Axis I (despite the fact

that a mental disorder is needed to give an IMD diagnosis). These sleep experts did

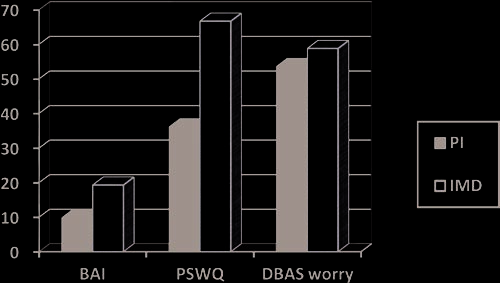

not have access to the insomnia patient’s scores on instruments such as the Beck

Anxiety Inventory (BAI) or the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PWSQ), but a

multivariate analysis of these measures suggested that these two groups indeed dif-

fered (that is, the Axis I group had significantly higher scores that were all above

the clinical cutoff for the measures, and those without an Axis I disorder had statis-

tically lower scores and the means were below the clinical cutoffs for these mea-

sures). Interestingly, the groups did not differ on a measure of worry about sleep;

the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale (DBAS). The DBAS

worry scores were in the pathological range, which suggests that the high level of

worry about sleep may be interpreted by some to be a sign of more global pathology

when it is in fact, merely a daytime symptom of insomnia (Fig. 1.1).

6

1 Anxiety and Insomnia: An Overview

Fig. 1.1

Anxiety measure scores are not pathological unless there is a comorbid Axis I disorder

Other studies have also suggested that there can be misconceptions about insom-

nia sufferers. For example, in a multisite evaluation of factors considered in dif-

ferential diagnosis for insomnia (Nowell et al., 1997), the presence of a mental

disorder tended to preclude consideration of concomitant sleep disorder diagnoses

such as Primary Insomnia, or Psychophysiological Insomnia, whereas the presence

of conditioned arousal or poor sleep habits tended to preclude consideration of an

insomnia “related to a mental disorder” diagnosis. Although conditioned arousal

and poor sleep habits could play a significant role in the insomnia of those with

comorbid problems such as anxiety disorders, this possibility tends to be ignored

by clinicians.

The utility of a primary versus secondary distinction also may be questionable

in light of the following evidence: (1) insomnia can precede Axis I disorders (Ford

& Kamerow, 1989; Weissman et al., 1997); (2) insomnia can effectively be treated

without necessarily treating the comorbid disorder (Lichstein, Wilson, & Johnson,

2000); (3) insomnia may be a risk factor for other disorders, including anxiety

disorders (Ford & Kamerow, 1989); and (4) as many as half of individuals complain

of residual, persistent insomnia after remission from the so-called “primary” disor-

der (e.g., PTSD) (Zayfert & DeViva, 2004). Thus, distinguishing between a pri-

mary versus secondary insomnia may be more of a theoretical than a practical

enterprise (Lichstein, 2000).

Moreover, the relegation of insomnia to a secondary condition has dictated treat-

ment practices that are questionable. Conventional wisdom was to treat the pre-

sumed primary condition and the insomnia would purportedly resolve. However,

clinically significant levels of so-called “residual insomnia” remain in about half of

people successfully treated for their primary disorder only. For example, rates of

residual insomnia in depression have been reported as high as 53%, and there does

not appear to be any difference in residual insomnia rates between CBT and

pharmacotherapy for depression (Carney, Segal, Edinger, & Krystal, 2007).

The residual insomnia rate for PTSD is similarly high (Zayfert & DeViva, 2004).

Also, insomnia treatment in those with comorbid Axis I disorders has typically

The Case of Comorbid Insomnia: More Nosological Issues

7

shown improvement in the accompanying condition, and combined approaches

have shown some superiority to treating the so-called primary condition only

(Edinger, Wohlgemuth, Krystal, & Rice, 2005; Manber et al., 2008; Pollack et al.,

2008). Thus, the problem of residual insomnia and support for the superiority of

combination (sleep and the comorbid condition) treatment approaches casts doubt

on the practice of ignoring insomnia.

A particularly useful way of thinking about insomnia and comorbid conditions

is that insomnia can be partially, independently, or speciously related to the other

condition (Lichstein et al., 2000). This means that the etiological significance of

insomnia in those with anxiety disorders can vary considerably. In some, insomnia

may truly represent an

absolute

secondary sleep difficulty caused by an anxiety

process and eliminated by successful anxiety disorder treatment. In others, the

insomnia/anxiety relationship is only

partial

as the two conditions have some,

albeit not total independence. In such cases, successful anxiety-targeted therapy

might be expected to reduce but not eliminate presenting insomnia symptoms. Still

in others, the insomnia/anxiety relationship is

specious

in that the comorbidity of

two essentially independent conditions is mistaken for causality. In this latter case,

anxiety-focused therapies would be expected to have little, if any, effect on present-

ing sleep difficulties. This conceptualization has heuristic appeal for explaining

various etiologic pathways and treatment outcomes for sleep difficulties presented

by those with anxiety disorders. However, in practice, it is often difficult to identify

the various subtypes this taxonomy proposes given the frequent unreliability of

patients’ historical reports and the lack of any objective assay to discriminate them

from each other. Moreover, the manner in which insomnia and anxiety interact

remains poorly understood, so it appears most appropriate to consider insomnia a

comorbid condition that may often warrant special recognition and separate treat-

ment attention in those with anxiety.

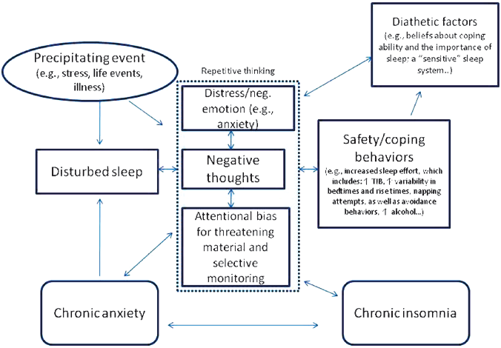

Cognitive Behavioral Model of Insomnia and Anxiety

Now, we turn from nosology to a proposed cognitive-behavioral model of etiology

for insomnia and anxiety. If we integrate the ideas included in several conceptual

models of insomnia (Harvey, 2002; Lichstein, 2000; Spielman, Caruso, & Glovinsky,

1987), we can envisage multiple different interacting or independent paths of risk

for developing diagnoses or symptoms of insomnia in the context of anxiety. We

will discuss Spielman’s model more thoroughly in the next chapter, but etiology in

insomnia is commonly regarded in diathesis-stress model terms. That is, there are

predisposing/diathetic factors in insomnia that in the absence of a precipitating

stressor would not be expected to result in exceeding the clinical threshold of

insomnia. However, the occurrence of a physical, environmental, or psychologi-

cal stressor could be disruptive enough to precipitate an episode of insomnia. Such

stressors could include experiencing a positive or negative life event, an environ-

mental change such as the introduction of a noisy roommate, multiple time-zone

8

1 Anxiety and Insomnia: An Overview

travel, interpersonal conflict, or a physical or mental health condition (such as an

anxiety disorder). An important element of Spielman’s model is the consideration

that reactions to the sleep problem tend to become important perpetuating factors

in insomnia. Negative thoughts and emotions, selective attention and monitoring of

sleep-threat related stimuli, and safety behaviors that undermine sleep regulation

and reinforce maladaptive beliefs about sleep all may sustain an insomnia problem

(Harvey, 2002). Thus, the model in Fig. 1.2 captures the idea that perpetuating and

precipitating factors are important in the initial onset of sleep disruption, but the