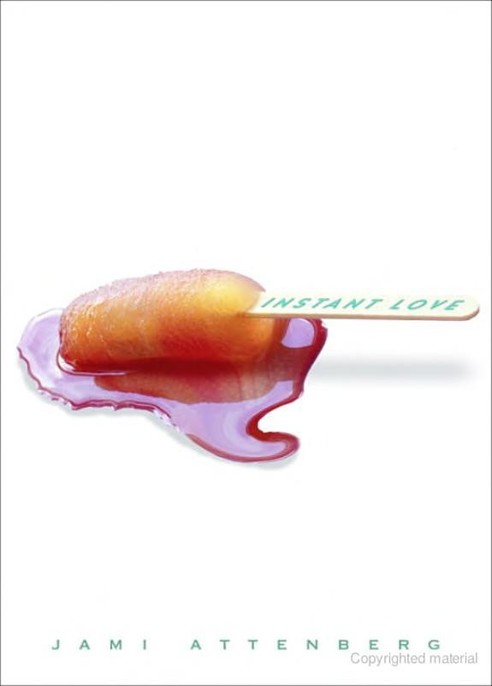

Instant Love

Authors: Jami Attenberg

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Short Stories (Single Author)

Contents

H

olly is getting her makeup done by the burnout girl she befriended at work. They’re in the bathroom at the back of the pharmacy, and Shelly’s dusting one perfect pastel-colored triangle on each eyelid. Same as hers. She’s been staring at Shelly for two nights a week, 5:00–9:00

PM

, most of senior year, and has fallen deeply in love with her makeup.

Holly has tried to make the same perfect triangles herself at home, usually with

Seventeen

magazine spread out next to her on the bathroom counter. She looks at the photos and diagrams and memorizes the quick tips, muttering directions under her breath as she stares into the mirror, but it’s no use. Her eyes end up looking more like Picasso’s than Madonna’s. It turns out she’s no good at blending in the makeup. She’s going to suck at blending in for the rest of her life.

Tonight she’s going on a date, that’s why all the makeupping. She’s going out with a boy named Christian who is nineteen and who likes the Smiths and the Cure and New Order. Holly is seventeen and likes New Order and Echo and the Bunny-men and Joy Division. She knows she should like the Smiths, but Morrissey seems like such a whiny turd. Holly has lied to Christian about this, because he

worships

Morrissey. Morrissey changed his life forever, that’s what Christian says. He’s a vegetarian now and everything. Meat

is

murder, he says.

Shelly likes Aerosmith and Judas Priest.

That’s how Holly and Christian met, because of music. They were both wearing the same New Order T-shirt, the one with the

Brotherhood

album cover (which is a

classic,

even though it is only a few years old), when Christian came in the pharmacy to pick up his father’s heart medicine. No one else wears those shirts in her hometown. Holly lives in a town so small she can barely breathe. That’s the joke, she’s heard it said before: If you want to breathe, go to the next town over.

Coincidentally, that’s where they sell New Order T-shirts, too, in the next town over. At that little shitty record store in the minimall, between the 7-Eleven and the dry cleaner’s. That’s where they both got their shirts. They talked about that record store for five minutes, how it was such a rip-off but it was the only place around. A line built up behind him, and she thought he was going to leave, but then he stepped to the side and waited, and her heart fucking flung at her chest, hard and fast and repeatedly, because oh my god,

this guy is going to like me

.

No one ever likes her like that.

Because of their age difference, Holly and Christian are keeping their romance a secret. No one wants anyone getting arrested for statutory anything.

Plus the engine on his car is so loud she can hear him coming from a block away, and she jokes about it with him, but she’s not kidding, that car is a piece of shit.

And he has shaved the sides of his head and left the hair on top long so that it spills over his narrow face in an awkward way and makes him look vaguely like a celery stick.

Also, there is the matter of Christian living in his father’s basement because he doesn’t feel like getting a job while halfheartedly taking community-college classes in accounting because he doesn’t feel like going away to college. He doesn’t feel like doing much of anything except riding around in his car and running errands for his dad, talking about Morrissey, and drinking beer from cans in paper sacks. Holly is two years younger than him, and already she knows she is going to blow him away in life, though she’s not sure if she’s allowed to feel that way yet, so she beats herself up for being a big snob. She is no better than her girlfriends, who say things like, “Like I would date a guy who wasn’t in National Honor Society” because all of her friends are smart-girl snobs.

That’s why she likes this burnout girl so much. Shelly thinks it’s normal to date a guy who goes to community college. Shelly thinks it’s OK to spend an hour putting on eye makeup. It doesn’t matter to Shelly if he smokes or drives a crappy car. He has a car,

chica

! (Shelly likes to translate words into Spanish whenever possible. It’s the only class she isn’t failing.) At least he has a car. At least you have a boyfriend.

SHELLY HAS A SECRET

that isn’t much of a secret at all. When she was ten, a neighbor kidnapped her and kept her in his basement for ten days. He was fat, with a belly like a pregnant woman’s, and he had a wandering eye. Holly remembers when it happened, because it was the first time she was aware of something bad happening to another kid her age. Sure, there had been divorced parents (like hers), skinned knees and broken arms, and Holly even knew a girl whose dog had died after getting hit by the FedEx truck. But no one she knew had got kidnapped and—she was guessing, everyone was guessing, but no one knew for sure except for the police and Shelly’s parents—raped by some psycho nutjob who got away with it for as long as he did because he was a regular churchgoer, and no one ever suspects a man who is one with God.

That’s what Holly’s mother said when they finally busted him. She slapped down the newspaper on the kitchen table, three cups of coffee into the morning, and yelled, “Anyone could see the man was crazy! Look at that eye! You wear one little crucifix around your neck and your shit don’t stink.”

Holly’s mother is a godless heathen. She says this proudly to her two friends in town, who are also divorced and also mothers. They spend a lot of time in the next town over.

She has thin black hair and is tiny and focused, like a firecracker right before it explodes. She is

always

suing Holly’s father for more child support. Every time he writes another book, she asks for more money. Holly has a younger sister, Maggie, who has lots of medical bills. Neurologists. Therapists. Pharmacists. “Plus they are two teenage girls, Bill,” her mother would say into the phone. “They eat, they shop, they breathe.”

The expenses,

her mother hisses.

Holly’s mother exhausts her.

Shelly moved away a few months after the trial. She went to live on the other side of the state with her dad, who blamed her mom for what happened. Her mother also blamed herself for what happened, because she was at work, and not at home waiting for her child. And she blamed herself for marrying her husband in the first place. She married him because he was the first one who asked. What if no one else asked? What if? Her life was just one big mistake leading up to her child being kidnapped and molested. So Shelly left and her mother began to drink, and she did this for a few years, she was very good at it, until her boss at the salon told her to cut it out, quit coming to work smelling like you’ve been making out with Bartles & Jaymes all night long or you’re fired. She got herself in a program, went to a lot of meetings, made a lot of apologies, and tried to get her daughter back. A mother should be with her daughter, don’t you think?

Shelly always complains when her mom is “twelve-stepping” her again.

Take her, said Shelly’s dad. It’s my turn for some fun. Shelly’s dad throws acid parties now. She sometimes visits him on the weekends and smokes pot with his girlfriend who is only ten years older than her and used to live in Korea and knows how to swear in ten different languages. He’s acting like it’s the sixties again, that’s what Shelly says when she comes back after a visit. He’s trying to turn back the hands of time.

El tiempo

.

They are taking turns, this family, with being fucked up. That’s what Holly thinks.

Shelly’s been back in town for a year, and everyone knows exactly who she is; no one has forgotten a thing. People don’t forget things like kidnap and rape and molestation and violation and major jail time in a town so small no one can breathe. No one will touch Shelly. No one wants to go near her, except for the other burnout girls. They recognize her as the kind of girl who has a particular understanding of extreme sorrows inflicted by a different kind of fate than applied to the rest of the world.