Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (44 page)

In the dark days of World War II, when German armies drove deep into the Caucasus, the Chechens tried to come to a friendly accommodation with the invaders. But the Germans had little aptitude for reaching out to unhappy Soviet subjects—yet another cause of their defeat in the East—and when the Nazis were finally driven back, Joseph Stalin had almost all the Chechens deported in retaliation for what he viewed as their treachery. Over a few weeks, beginning in late February 1944, about four hundred thousand Chechens were resettled, many to Kazakhstan, others farther away in Siberia. They were to remain in exile for thirteen years, sustained by their social structures, Sufi practices and dreams of home.

Nikita Khrushchev, a relatively more liberal-minded successor of Stalin, decided to “pardon” the Chechens. During 1956–1957, in a conciliatory move, he allowed them to return to their ancestral lands. In addition to sending them home, Khrushchev sought to reintegrate the Chechens fully into Soviet society. No doubt he was guided in this policy by his belief in the tenet of the Communist faith which held that class, and the equality and fraternity of all workers, would always trump ethnicity. George Kennan, perhaps the greatest American observer of the “Soviet experiment,” viewed this belief as a fatal flaw. For, as he noted, “national feelings have shown themselves to be more powerful as a political-emotional force than ones related, as is the Marxist ideology, to class.”

2

Kennan was right, and Khrushchev’s policies unwittingly set a time bomb ticking in the Caucasus. In the last three decades of the Cold War, Chechen nationalism did not die but rather waited for its moment, like a tree in winter waiting for spring. That spring came with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, when independence from Moscow was first declared by separatists in Chechnya. They had cleverly supported the successful democratic opposition to the coup plotters who briefly overthrew Gorbachev in August 1991 in a vain attempt to restore the central power of the Soviet Union. Chechen solidarity with Gorbachev’s democratic reforms made it hard for the rising Russian political star, Boris Yeltsin, to crack down on them, at least overtly. So the policy developed in Moscow eschewed brute force, aiming instead at the cultivation of a friendly antiseparatist “front” in Chechnya, one that was intended to keep the republic well within the Russian Federation. If Chechnya ever escaped Moscow’s gravitational pull, other non-Russian republics within the federation were sure to follow.

Between the winter of 1992 and the summer of 1994, jockeying for position by both sides was intense, and it was clearly a prelude to armed conflict. Thanks to Khrushchev’s reintegration policy toward the Chechens, a number of them had risen to command levels in the Soviet military, most notably air force general Dzhokhar Dudayev and an artillery colonel named Aslan Maskhadov. Dudayev had been elected the first president of the Chechen Republic in September 1991, while Maskhadov was soon to rise and become chief of staff of the fledgling Chechen military.

Given that Dudayev had to deal with all manner of affairs of state, the demands of planning for the republic’s defense fell for the most part on his colleague’s shoulders. Maskhadov had been born in exile in Kazakhstan in the fall of 1951 and was a young boy when his family was allowed to return to Chechnya. He reached manhood intent upon becoming a professional military officer, his most challenging service coming in the waning days of the Cold War, when he was posted first to Hungary and then later to Lithuania. Maskhadov got his first serious glimpse of separatism in the wake of the Lithuanian declaration of independence in March 1990. After many months of simmering tensions, Soviet forces were called out to curtail the growing unrest in January 1991.

Just days before the American air force unleashed its strategic bombing campaign against Saddam Hussein in the first Gulf War, Maskhadov participated in a military crackdown against Lithuanian freedom demonstrators. Thirteen of them were killed in this attempt to show that the Soviets were still in control of their country—yet another of the world’s events that have come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Maskhadov did his duty in Lithuania but suffered growing doubts about the rectitude of such actions. Gorbachev had second thoughts too and allowed a referendum on independence to be held the following month. The pro-independence faction won with a whopping 90 percent of the voters affirming the anti-Moscow line. Lithuania was on its way to freedom, and just ten months later the Soviet Union itself would disintegrate. Maskhadov retired from the army shortly thereafter, returning home to Chechnya and affiliating himself with the independence movement. Events in Lithuania tugged at his conscience, but the prospect of Chechen freedom quickly won his heart.

For an artillery officer, Maskhadov showed considerable aptitude for irregular military operations. In the skirmishing between the pro-and anti-Moscow factions, Maskhadov developed and increasingly oversaw a campaign comprised largely of small-scale, hit-and-run firefights. His forces also mounted many raids on trains carrying munitions—though these may have been sham actions, providing cover for illicit arms deals made with corrupt Russian officials. Whatever the truth of the matter, a profusion of weapons reached the insurgents.

It turned out that the arming up of the Chechens happened just in time, for Moscow, reluctant to be seen as intervening directly, was passing weapons to friendly lowland clans in the north who feared being ruled by Chechen highlanders from the mountainous south. And a stream of Russian “volunteers” was trickling into the pro-Moscow faction’s ranks, leavening them with skilled professionals. When they finally moved against the insurgents in November 1994—a direct drive on the capital, Grozny—Maskhadov and Chechen rebel forces were waiting. The genius of their defensive concept of operations lay in the wide dispersion of hundreds of small fire teams, armed with little more than rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). The pro-Moscow faction was swiftly routed.

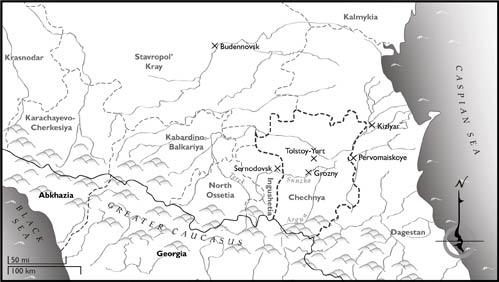

Conflict in the Transcaucasus

The Russians redoubled their efforts and sent in some forty thousand of their own regular forces a month later, at Christmastime. Maskhadov had prepared even more thoroughly for this second assault. His small bands, amounting by his account to no more than five or six thousand fighters in all,

3

employed a bewildering array of irregular tactics, popping up out of sewers and fighting from various floors of high-rise buildings in the city center. They learned to hit the front and rear vehicles of Russian convoys first, in order to immobilize the convoy, then struck at close range with sawed-off RPGs—shorter barrels made for greater velocity—that had napalm charges attached, starting fires on the inside and often blowing up the invaders’ tanks. Chechen

GHAZAVAT

fighters were an early generation of suicide bombers, specifically used to blow up tanks and other armored vehicles. In the words of two journalists who were eyewitnesses to much of this conflict, “the lack of fixed defenses and the mobility of the small groups of fighters were in fact their strength.”

4

Thus an archetypal irregular battle unfolded. An invading army comprised of big, balky formations was beaten by forces just over a tenth their size—and with no air support—because the defenders had broken themselves into small teams of no more than a dozen or so each, fanned out across the city, and swarmed the enemy in a series of simultaneous attacks from all directions. Maskhadov’s motto was “less centralization, more coordination.”

5

It was a defensive version of the swarming style that Garibaldi had employed on the offensive in his fight for the city of Palermo more than a century earlier.

Unlike the royalist forces whose leaders capitulated in the face of Garibaldi’s attack, however, the Russians only redoubled their efforts when their first assaults on Grozny failed. Thousands more Russian troops were poured into Chechnya, advancing in areas beyond Grozny even while the fighting still raged there. Dudayev and Maskhadov faced the reality that, after more than a month of hard fighting, Grozny would have to be given over to the enemy.

They now executed a remarkable fighting retreat as the small bands of Chechen fighters headed off in several directions. Most went south to the mountainous region of Chechnya, where they continued to defend, this time in rough country. Other insurgents were deployed well behind the Russian lines to strike at vulnerable posts and logistical nodes as circumstances permitted. Often, like Kitson’s pseudo gangs, the Chechens—many of them veterans of the Red Army—dressed up as Russian troops to infiltrate them before opening fire.

Still, sheer weight of numbers kept the Russians moving forward, despite casualties now mounting into the tens of thousands among killed, wounded, and missing. The Chechens suffered even more severely, in relative terms. Comparatively they may have lost only over two thousand fighters killed in action by this time, but this was a large percentage of their total combat forces engaged in the campaign.

At this point a desperate diversionary raid was mounted on the southern Russian town of Budennovsk by one of Maskhadov’s colleagues, Shamil Basayev. Where Maskhadov was a professional soldier with a flair for irregular operations, Basayev was at heart a terrorist. Perhaps he was driven to such extreme behavior by the loss of much of his family in a Russian air raid fewer than two months before the attack on Budennovsk. Perhaps he was enraged by the indifference of the international community to Chechen suffering. As he once asked the journalist Anatol Lieven, who was reporting from amid the fighting, “Who cares about our moral position? Who from abroad has helped us, while Russia has brutally ignored every moral rule?”

6

There would be continual, growing tension between Basayev and Maskhadov in the coming years, but now, in June 1995, there was consensus about the need to do something very dramatic in order to arrest further Russian progress on the ground in Chechnya. That something turned out to be Basayev’s infiltration of just over a hundred Chechen fighters, including several female snipers, into the town of Budennovsk, which they completely shot up, killing scores of innocent people.

Engaged by Russian forces, Basayev’s men holed up in the city hospital with more than a thousand hostages. After Russian troops failed in their attempts to storm the hospital, Premier Viktor Chernomyrdin entered into direct negotiations with Basayev for the release of the hostages. Basayev’s condition was the Russians’ suspension of military operations in Chechnya. His raiders were to be guaranteed safe passage home and would take some hostages along on the return route as insurance.

The terms of the deal struck along these lines were honored on both sides—no doubt a surprise to all involved. The resulting respite in the war in Chechnya proper was to give Maskhadov—by now promoted to general—time to plan for an offensive to drive the Russians out of his country. But his was to be no guerrilla hit-and-run campaign, nor was it to rely on terrorism, though terrorist acts were to be committed. Instead Maskhadov would pioneer a concept of operations in which a force of just several thousand fighters, formed up in hundreds of very small units, would mount an offensive directly against a far larger, more heavily armed enemy force that enjoyed complete air superiority.

That Maskhadov prevailed in this campaign provides either evidence of one of history’s most exceptional military miracles or a persuasive example of the inherent superiority of a small, swarming irregular force against a

traditionally organized opponent. In either case, a true master of the battlefield emerged to carry it off.

*

Before the fighting resumed, however, an actual chance for peace arose. Maskhadov, the former Russian army officer, negotiated with the enemy an agreement by which Chechens would turn in their arms, or promise to keep them in their homes, as invading troops gradually pulled out. Through the summer of 1995, it seemed that this phased withdrawal might work. Elections were even planned, with the Russians again supporting a pro-Moscow faction that would bring the rebellious republic back under control. But violations of the agreement by both sides grew during the fall. All too many innocent Chechens and hapless Russian recruits were being killed.

By year’s end the prospects for peace had seriously dimmed. The Chechens now mounted their second significant terrorist attack outside their own territory. Early in January about two hundred Chechen fighters under the command of Salman Radujev made their way to the town of Kizlyar in the Republic of Dagestan. Their apparent goal was to strike the airfield there, destroying Russian aircraft and possibly seizing some of the cargo supposed to have just arrived. But when they reached the airfield there were few aircraft to destroy and little cargo to speak of. The Russians, who may have known that the attack was coming, responded to the assault and put the raiders on the run.