Irish Fairy Tales (11 page)

This gentleman's name was Fergus Fionnliath, and his stronghold was near the harbour of Galway. Whenever a dog barked he would leap out of his seat, and he would throw everything that he owned out of the window in the direction of the bark. He gave prizes to servants who disliked dogs, and when he heard that a man had drowned a litter of pups he used to visit that person and try to marry his daughter.

Now Fionn, the son of Uail, was the reverse of Fergus Fionnliath in this matter, for he delighted in dogs, and he knew everything about them from the setting of the first little white tooth to the rocking of the last long yellow one. He knew the affections and antipathies which are proper in a dog; the degree of obedience to which dogs may be trained without losing their honourable qualities or becoming servile and suspicious; he knew the hopes that animate them, the apprehensions which tingle in their blood, and all that is to be demanded from, or forgiven in, a paw, an ear, a nose, an eye, or a tooth; and he understood these things because he loved dogs, for it is by love alone that we understand anything.

Among the three hundred dogs which Fionn owned there were two to whom he gave an especial tenderness, and who were his daily and nightly companions. These two were Bran and Sceólan, but if a person were to guess for twenty years he would not find out why Fionn loved these two dogs and why he would never be separated from them.

Fionn's mother, Muirne, went to wide Allen of Leinster to visit her son, and she brought her young sister Tuiren with her. The mother and aunt of the great captain were well treated among the Fianna, first, because they were parents to Fionn, and second, because they were beautiful and noble women.

No words can describe how delightful Muirne wasâshe took the branch; and as to Tuiren, a man could not look at her without becoming angry or dejected. Her face was fresh as a spring morning; her voice more cheerful than the cuckoo calling from the branch that is highest in the hedge; and her form swayed like a reed and flowed like a river, so that each person thought she would surely flow to him.

Men who had wives of their own grew moody and downcast because they could not hope to marry her, while the bachelors of the Fianna stared at each other with truculent, bloodshot eyes, and then they gazed on Tuiren so gently that she may have imagined she was being beamed on by the mild eyes of the dawn.

It was to an Ulster gentleman, Iollan Eachtach, that she gave her love, and this chief stated his rights and qualities and asked for her in marriage.

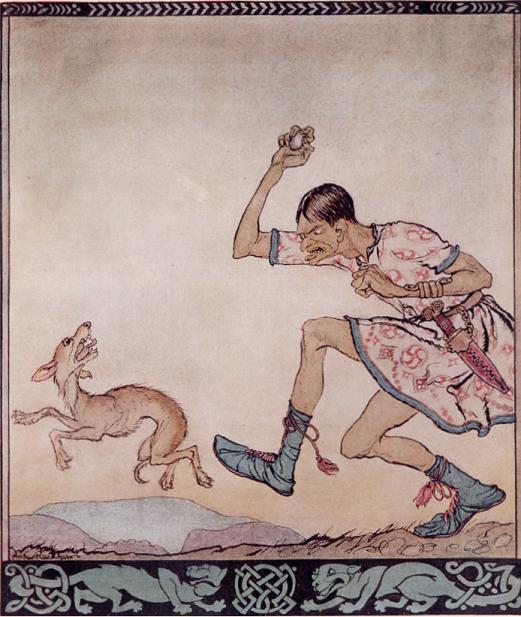

A man who did not like dogs. In fact, he hated them. When he saw one he used to go black in the face, and he threw rocks at it until it got out of sight

Now Fionn did not dislike the men of Ulster, but either he did not know them well or else he knew them too well, for he made a curious stipulation before consenting to the marriage. He bound Iollan to return the lady if there should be occasion to think her unhappy, and Iollan agreed to do so. The sureties to this bargain were Caelte mac Ronán, Goll mac Morna, and Lugaidh. Lugaidh himself gave the bride away, but it was not a pleasant ceremony for him, because he also was in love with the lady, and he would have preferred keeping her to giving her away. When she had gone he made a poem about her, beginning:

There is no more light in the skyâ

And hundreds of sad people learned the poem by heart.

Chapter 2

W

hen Iollan and Tuiren were married they went to Ulster, and they lived together very happily. But the law of life is change; nothing continues in the same way for any length of time; happiness must become unhappiness, and will be succeeded again by the joy it had displaced. The past also must be reckoned with; it is seldom as far behind us as we could wish: it is more often in front, blocking the way, and the future trips over it just when we think that the road is clear and joy our own.

Iollan had a past. He was not ashamed of it; he merely thought it was finished, although in truth it was only beginning, for it is that perpetual beginning of the past that we call the future.

Before he joined the Fianna he had been in love with a lady of the ShÃ, named Uct Dealv (Fair Breast), and they had been sweethearts for years. How often he had visited his sweetheart in Faery! With what eagerness and anticipation he had gone there; the lover's whistle that he used to give was known to every person in that ShÃ, and he had been discussed by more than one of the delicate sweet ladies of Faery.

“That is your whistle, Fair Breast,” her sister of the Shà would say.

And Uct Dealv would reply: “Yes, that is my mortal, my lover, my pulse, and my one treasure.”

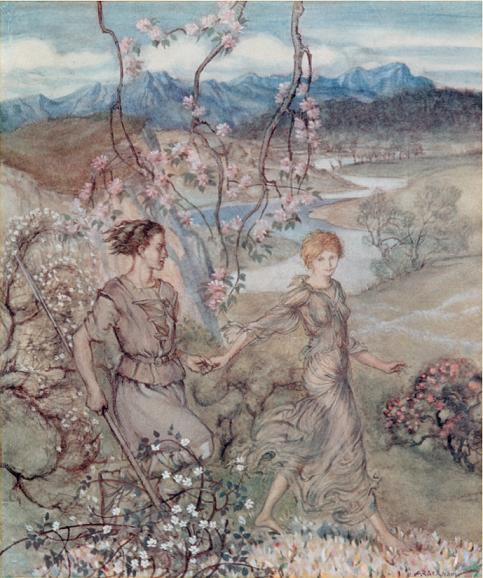

She laid her spinning aside, or her embroidery if she was at that, or if she were baking a cake of fine wheaten bread mixed with honey she would leave the cake to bake itself and fly to Iollan. Then they went hand in hand in the country that smells of apple-blossom and honey, looking on heavy-boughed trees and on dancing and beaming clouds. Or they stood dreaming together, locked in a clasping of arms and eyes, gazing up and down on each other, Iollan staring down into sweet grey wells that peeped and flickered under thin brows, and Uct Dealv looking up into great black ones that went dreamy and went hot in endless alternation.

Then Iollan would go back to the world of men, and Uct Dealv would return to her occupations in the Land of the Ever Young.

“What did he say?” her sister of the Shà would ask.

“He said I was the Berry of the Mountain, the Star of Knowledge, and the Blossom of the Raspberry.”

“They always say the same thing,” her sister pouted.

“But they look other things,” Uct Dealv insisted. “They feel other things,” she murmured; and an endless conversation recommenced.

Then for some time Iollan did not come to Faery, and Uct Dealv marvelled at that, while her sister made an hundred surmises, each one worse than the last.

“He is not dead or he would be here,” she said. “He has forgotten you, my darling.”

News was brought to Tlr na n-Og of the marriage of Iollan and Tuiren, and when Uct Dealv heard that news her heart ceased to beat for a moment, and she closed her eyes.

Then they went hand in hand in the country that smells

of apple-blossom and honey

“Now!” said her sister of the ShÃ. “That is how long the love of a mortal lasts,” she added, in the voice of sad triumph which is proper to sisters.

But on Uct Dealv there came a rage of jealousy and despair such as no person in the Shà had ever heard of, and from that moment she became capable of every ill deed; for there are two things not easily controlled, and they are hunger and jealousy. She determined that the woman who had supplanted her in Iollan's affections should rue the day she did it. She pondered and brooded revenge in her heart, sitting in thoughtful solitude and bitter collectedness until at last she had a plan.

She understood the arts of magic and shape-changing, so she changed her shape into that of Fionn's female runner, the best-known woman in Ireland; then she set out from Faery and appeared in the world. She travelled in the direction of Iollan's stronghold.

Iollan knew the appearance of Fionn's messenger, but he was surprised to see her.

She saluted him.

“Health and long life, my master.”

“Health and good days,” he replied. “What brings you here, dear heart?”

“I come from Fionn.”

“And your message?” said he.

“The royal captain intends to visit you.”

“He will be welcome,” said Iollan. “We shall give him an Ulster feast.”

“The world knows what that is,” said the messenger courteously. “And now,” she continued, “I have messages for your queen.”

Tuiren then walked from the house with the messenger, but when they had gone a short distance Uct Dealv drew a hazel rod from beneath her cloak and struck it on the queen's shoulder, and on the instant Tuiren's figure trembled and quivered, and it began to whirl inwards and downwards, and she changed into the appearance of a hound.

It was sad to see the beautiful, slender dog standing shivering and astonished, and sad to see the lovely eyes that looked out pitifully in terror and amazement. But Uct Dealv did not feel sad. She clasped a chain about the hound's neck, and they set off westward towards the house of Fergus Fionnliath, who was reputed to be the unfriendliest man in the world to a dog. It was because of his reputation that Uct Dealv was bringing the hound to him. She did not want a good home for this dog: she wanted the worst home that could be found in the world, and she thought that Fergus would revenge for her the rage and jealousy which she felt towards Tuiren.

Chapter 3

A

s they paced along Uct Dealv railed bitterly against the hound, and shook and jerked her chain. Many a sharp cry the hound gave in that journey, many a mild lament.

“Ah, supplanter! Ah, taker of another girl's sweetheart!” said Uct Dealv fiercely. “How would your lover take it if he could see you now? How would he look if he saw your pointy ears, your long thin snout, your shivering, skinny legs, and your long grey tail. He would not love you now, bad girl!”

“Have you heard of Fergus Fionnliath,” she said again, “the man who does not like dogs?”

Tuiren had indeed heard of him.

“It is to Fergus I shall bring you,” cried Uct Dealv. “He will throw stones at you. You have never had a stone thrown at you. Ah, bad girl! You do not know how a stone sounds as it nips the ear with a whirling buzz, nor how jagged and heavy it feels as it thumps against a skinny leg. Robber! Mortal! Bad girl! You have never been whipped, but you will be whipped now. You shall hear the song of a lash as it curls forward and bites inward and drags backward. You shall dig up old bones stealthily at night, and chew them against famine. You shall whine and squeal at the moon, and shiver in the cold, and you will never take another girl's sweetheart again.”

And it was in those terms and in that tone that she spoke to Tuiren as they journeyed forward, so that the hound trembled and shrank, and whined pitifully and in despair.

They came to Fergus Fionnliath's stronghold, and Uct Dealv demanded admittance.

“Leave that dog outside,” said the servant.

“I will not do so,” said the pretended messenger.

“You can come in without the dog, or you can stay out with the dog,” said the surly guardian.

“By my hand,” cried Uct Dealv, “I will come in with this dog, or your master shall answer for it to Fionn.”

At the name of Fionn the servant almost fell out of his standing. He flew to acquaint his master, and Fergus himself came to the great door of the stronghold.

“By my faith,” he cried in amazement, “it is a dog.”

“A dog it is,” growled the glum servant.

“Go you away,” said Fergus to Uct Dealv, “and when you have killed the dog come back to me and I will give you a present.”

“Life and health, my good master, from Fionn, the son of Uail, the son of Baiscne,” said she to Fergus.

“Life and health back to Fionn,” he replied. “Come into the house and give your message, but leave the dog outside, for I don't like dogs.”

“The dog comes in,” the messenger replied.